Biden proposes weight loss drug coverage for people on Medicare and Medicaid

Posted on 11/26/2024

The Biden administration plans to require Medicare and Medicaid to offer coverage of weight loss medications for people seeking obesity treatment.

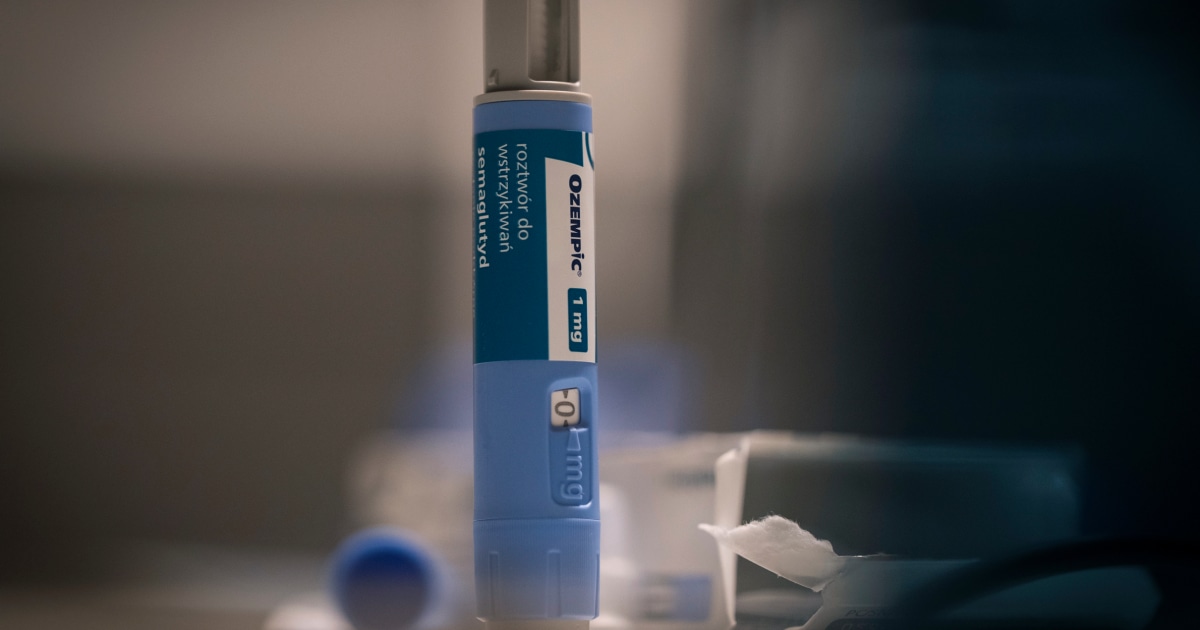

The new rule, which was proposed by the administration Tuesday, would dramatically expand access to anti-obesity medications such as Ozempic and Wegovy, from Novo Nordisk, and Mounjaro and Zepbound, from Eli Lilly.

Medicare has been barred from paying for weight loss drugs, unless they're used to treat conditions like diabetes or to manage an increased risk of heart disease. States can decide whether to cover obesity drugs under Medicaid, but the majority don't.

The Biden administration is proposing to reinterpret the law barring coverage by classifying obesity drugs as treatment for a "chronic disease," rather than as weight loss medications.

"The medical community today agrees that obesity is a chronic disease," Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure said on a call with reporters Tuesday. "These drugs are the beginning of a revolution in the way that weight is controlled."

The change would dramatically reduce out-of-pocket costs for the drugs. Today, a month's supply of weight loss drugs can cost $1,000 or more, according to estimates from a White House official.

The federal government will pick up the majority of that cost, about $25 billion for Medicare and $11 billion for Medicaid over 10 years, government officials said Tuesday. States will need to pay about $3.8 billion.

They don't expect it will increase out-of-pocket premiums.

"The Inflation Reduction Act has made historic strides in reducing the cost of prescriptions for our nation's seniors and those on Medicare, including a $2,000 out-of-pocket cap and the IRA premium stabilization policies," CMS Deputy Administrator Dr. Meena Seshamani said on the call.

The proposal still requires a 60-day public comment period before it can go into effect, leaving it up to the incoming Trump administration whether to finalize it.

Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at KFF, a nonprofit group that researches health policy issues, said that it's "an open question" whether the incoming Trump administration will follow through, given that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. hasn't been so keen on the class of drugs.

President-elect Donald Trump this month tapped Kennedy to head the Department of Health and Human Services.

"RFK Jr. has expressed skepticism of these drugs, but Dr. Oz has praised them," Levitt said, referring to Mehmet Oz, Trump's pick to head the CMS. "Ultimately, this decision is likely to be made by the White House, which may be hesitant to stand in the way of coverage that will probably be very popular among many seniors."

More than 40% of Americans are considered obese. Obesity, a chronic disease, puts people at risk for heart disease, diabetes, breathing problems, stroke and some cancers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new rule would expand access to the drugs for 3.4 million Americans who use Medicare and another 4 million people enrolled in Medicaid, the White House official said.

About 72 million Americans were enrolled in Medicaid as of July, according to the CMS. Almost 68 million are enrolled in Medicare.

Another 154 million Americans get health insurance through their work, according to KFF.

Research suggests that there are significant disparities in who receives weight loss drugs. The health care analytics company PurpleLab found racial disparities in who is able to get semaglutide, the ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy.

About 85% of semaglutide prescriptions were dispensed to white people in 2023, the company's data found. When insurance doesn't cover the drug, its high cost becomes a barrier for many low- and middle-income Americans, doctors have said.

Expanding coverage to patients who rely on Medicare and Medicaid could reduce some disparities.

“Our Medicare and Medicaid populations are some of the most at-risk and they do not have access to any anti-obesity medication,” Dr. Laure DeMattia, a bariatric medicine specialist in Norman, Oklahoma, told NBC News in March.

On the call Tuesday, officials said that people may not be getting access to the care they need. Government data shows that Medicare Advantage plans overturn 80% of their decision to deny claims when those claims are appealed. However, fewer than 4% of denied claims are appealed.

The issue is fast becoming a workplace matter, too, as the drugs' popularity increases and employers balance program costs and their workers' needs.

Survey results published last month in Health Affairs found that less than a fifth of large companies in the United States offered health insurance plans that covered weight loss drugs.

Lawmakers, notably, Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., have said that due to the high cost of the drugs, it could “bankrupt” the health care system if the federal government provided coverage. Earlier this year, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, led by Sanders, grilled the CEO of Novo Nordisk over the high cost of Ozempic and Wegovy.

Outside experts weren't so sure.

"Will it break the bank? I don't think so," said Dr. Susan Spratt, an endocrinologist and senior medical director at the Population Health Management Office at Duke Health in North Carolina. "If we reduce dialysis, stroke, heart attack, sleep apnea, blindness, disability, costs of total care should go down."

Weight loss drugs like Wegovy are injectable medications of semaglutide. The drugs work because they mimic a hormone called GLP-1, which helps control blood sugar, manage people's metabolism and help them feel full.

Drugmakers are working on dozens more GLP-1 drugs, studying their long-term effects and exploring how they might help with other conditions.

The new rule, which was proposed by the administration Tuesday, would dramatically expand access to anti-obesity medications such as Ozempic and Wegovy, from Novo Nordisk, and Mounjaro and Zepbound, from Eli Lilly.

Medicare has been barred from paying for weight loss drugs, unless they're used to treat conditions like diabetes or to manage an increased risk of heart disease. States can decide whether to cover obesity drugs under Medicaid, but the majority don't.

The Biden administration is proposing to reinterpret the law barring coverage by classifying obesity drugs as treatment for a "chronic disease," rather than as weight loss medications.

"The medical community today agrees that obesity is a chronic disease," Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure said on a call with reporters Tuesday. "These drugs are the beginning of a revolution in the way that weight is controlled."

The change would dramatically reduce out-of-pocket costs for the drugs. Today, a month's supply of weight loss drugs can cost $1,000 or more, according to estimates from a White House official.

The federal government will pick up the majority of that cost, about $25 billion for Medicare and $11 billion for Medicaid over 10 years, government officials said Tuesday. States will need to pay about $3.8 billion.

They don't expect it will increase out-of-pocket premiums.

"The Inflation Reduction Act has made historic strides in reducing the cost of prescriptions for our nation's seniors and those on Medicare, including a $2,000 out-of-pocket cap and the IRA premium stabilization policies," CMS Deputy Administrator Dr. Meena Seshamani said on the call.

The proposal still requires a 60-day public comment period before it can go into effect, leaving it up to the incoming Trump administration whether to finalize it.

Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at KFF, a nonprofit group that researches health policy issues, said that it's "an open question" whether the incoming Trump administration will follow through, given that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. hasn't been so keen on the class of drugs.

President-elect Donald Trump this month tapped Kennedy to head the Department of Health and Human Services.

"RFK Jr. has expressed skepticism of these drugs, but Dr. Oz has praised them," Levitt said, referring to Mehmet Oz, Trump's pick to head the CMS. "Ultimately, this decision is likely to be made by the White House, which may be hesitant to stand in the way of coverage that will probably be very popular among many seniors."

More than 40% of Americans are considered obese. Obesity, a chronic disease, puts people at risk for heart disease, diabetes, breathing problems, stroke and some cancers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new rule would expand access to the drugs for 3.4 million Americans who use Medicare and another 4 million people enrolled in Medicaid, the White House official said.

About 72 million Americans were enrolled in Medicaid as of July, according to the CMS. Almost 68 million are enrolled in Medicare.

Another 154 million Americans get health insurance through their work, according to KFF.

Research suggests that there are significant disparities in who receives weight loss drugs. The health care analytics company PurpleLab found racial disparities in who is able to get semaglutide, the ingredient in Ozempic and Wegovy.

About 85% of semaglutide prescriptions were dispensed to white people in 2023, the company's data found. When insurance doesn't cover the drug, its high cost becomes a barrier for many low- and middle-income Americans, doctors have said.

Expanding coverage to patients who rely on Medicare and Medicaid could reduce some disparities.

“Our Medicare and Medicaid populations are some of the most at-risk and they do not have access to any anti-obesity medication,” Dr. Laure DeMattia, a bariatric medicine specialist in Norman, Oklahoma, told NBC News in March.

On the call Tuesday, officials said that people may not be getting access to the care they need. Government data shows that Medicare Advantage plans overturn 80% of their decision to deny claims when those claims are appealed. However, fewer than 4% of denied claims are appealed.

The issue is fast becoming a workplace matter, too, as the drugs' popularity increases and employers balance program costs and their workers' needs.

Survey results published last month in Health Affairs found that less than a fifth of large companies in the United States offered health insurance plans that covered weight loss drugs.

Lawmakers, notably, Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., have said that due to the high cost of the drugs, it could “bankrupt” the health care system if the federal government provided coverage. Earlier this year, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, led by Sanders, grilled the CEO of Novo Nordisk over the high cost of Ozempic and Wegovy.

Outside experts weren't so sure.

"Will it break the bank? I don't think so," said Dr. Susan Spratt, an endocrinologist and senior medical director at the Population Health Management Office at Duke Health in North Carolina. "If we reduce dialysis, stroke, heart attack, sleep apnea, blindness, disability, costs of total care should go down."

Weight loss drugs like Wegovy are injectable medications of semaglutide. The drugs work because they mimic a hormone called GLP-1, which helps control blood sugar, manage people's metabolism and help them feel full.

Drugmakers are working on dozens more GLP-1 drugs, studying their long-term effects and exploring how they might help with other conditions.

Comments( 0 )

0 0 2

0 0 4

0 0 4

0 0 4