Tulsi Gabbard: Trump’s pick for intel chief has deeply rooted distrust of agencies she would oversee

Posted on 11/22/2024

In 2020, the woman who has become Donald Trump’s pick to be the nation’s top spymaster met with one of the most infamous leakers of all time.

Tulsi Gabbard, then in the midst of a failed bid for the Democratic nomination for president, met with Daniel Ellsberg, a military analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times and The Washington Post in the 1970s and was charged with violations of the Espionage Act. He argued to her that it should be unconstitutional to charge officials who leak classified information to media outlets with espionage.

Gabbard agreed, declaring the practice “insanity.” Later that year, she introduced a bill in the House called the “Protect Brave Whistleblowers Act,” designed to shield people like Ellsberg. She wrote two more bills that same week supporting Julian Assange and Edward Snowden, who were behind two of the biggest US national security leaks of the 21st Century.

Trump’s selection of Gabbard to run the Office of the Director of National Intelligence has quickly drawn scrutiny because of her relative inexperience in the intelligence community and her public adoption of positions on Syria and the war in Ukraine that many national security officials see as Russian propaganda.

But where she is perhaps most at odds with the agencies she may soon be tasked with leading is her distrust of broad government surveillance authorities and her support for those willing to expose some of the intelligence community’s most sensitive secrets.

It’s also where she may come into conflict with Trump’s own past record — even as she appears to represent an evolution of the MAGA movement toward a more youthful, techno-libertarian vision of the anti-surveillance faction of the Republican Party. It was the first Trump administration, after all, that in 2019 took the unprecedented step of charging Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, with Espionage Act violations for soliciting and publishing classified information.

“Tulsi Gabbard is a highly unusual pick for Director of National Intelligence in an administration that has nominated some very solid people, like Marco Rubio, Elise Stefanik and Mike Waltz, because she’s somebody who clearly thinks that Edward Snowden should get away scot-free from stealing classified information,” said Jamil Jaffer, a former George W. Bush administration associate White House counsel and founder and executive director of the National Security Institute at George Mason University’s law school.

Gabbard has fiercely defended Assange, introducing a bill in 2020 opposing his extradition and prosecution. And her legislation defending Snowden, the contractor who in 2013 revealed the existence of the bulk collection of American phone records by the National Security Agency before fleeing to Russia, called on the federal government to drop all charges.

Both men are broadly seen as enemies of the state within the intelligence community. And the information they have exposed, officials say, has done grievous harm to America’s ability to collect and protect intelligence.

But both are also causes that have drawn a curious cross-section of political support, from the far left — Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has also opposed the extradition of Assange — to the libertarian-leaning right that contains both Trump allies like Sen. Rand Paul as well as critics such as former Rep. Justin Amash. Former Rep. Matt Gaetz, Trump’s pick to be attorney general, was one of two lawmakers to co-sponsor of Gabbard’s Snowden legislation.

It’s an unusual coalition that long predates — and in some ways exists outside of — Trump’s own deep skepticism of the “deep state” intelligence community, fueled by his claims that the FBI and other intelligence agencies illegally surveilled him as part of a political witch hunt.

Since arriving in Washington roughly a dozen years ago, Gabbard has evolved from a Democratic congresswoman who ran for president in 2020 to a Trump-endorsing Fox News regular who defected to the Republican Party earlier this year.

Interviews with former lawmakers and congressional aides who served with Gabbard as well as a reading of her 2024 memoir highlight a political chameleon who has maintained a populist and isolationist worldview, a willingness to buck party orthodoxy and a tendency to distrust authority figures that her critics say veers into outright conspiracy theory.

“People have core values and beliefs, and Tulsi, I believe, kind of lacks that,” said one Democrat who was close to Gabbard while they were in Congress together.

Gabbard did not respond to CNN’s request for an interview. Trump in a statement announcing her selection said Gabbard would bring a “fearless spirit that has defined her illustrious career to our Intelligence Community, championing our Constitutional Rights, and securing Peace through Strength.”

Gabbard proposed repealing Patriot Act

If confirmed, Gabbard will be the most markedly anti-surveillance official to lead the intelligence community in the post-9/11 era. Her animus towards what she has described as the “national security state and its warmongering friends,” hellbent on using the Espionage Act and other tools to punish its enemies, raises questions about whether she might seek to reshape the rules by which American intelligence agencies have been collecting, searching and using intelligence for decades.

In December 2020, shortly before she left Congress, Gabbard introduced legislation that would repeal the Patriot Act and Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, two of the most significant surveillance authorities passed by Congress after September 11, 2001. Like her other legislative attempts on spying issues, it went nowhere.

The DNI’s primary responsibility — beyond his or her role in determining what intelligence the president sees every day in his daily brief — is over the budget and priorities of the 18 agencies that make up the intelligence community. Because of that, it would be a complicated and difficult — though not impossible — task for Gabbard to unilaterally dismantle intelligence collection under Section 702.

In theory, Gabbard could issue an order to the intelligence community not to use 702 at all, but the Defense Department and Congress would likely push back on that, said Glenn Gerstell, former general counsel at the National Security Agency.

Getting rid of Section 702 entirely would address Gabbard’s concern — shared by civil liberties advocates in both parties — that the law offers too many ways for the intelligence community to surveil Americans without a warrant. But it would also dramatically curtail America’s ability to spy on foreign adversaries overseas, Gerstell said.

“If you were to eliminate just that one statute, you could take about 60% or 70% of the pages of (the president’s daily brief) and just throw it out before it even gets to the commander in chief,” Gerstell said. “And I can’t imagine why any commander in chief would want to operate in this world blindfolded.”

Fighting against a ‘cabal of warmongers’

As both a Democrat and a Republican, Gabbard has espoused a firmly isolationist, anti-war ideology — an organizing principle that fit her identity both as an up-and-coming progressive star and then, later, an adherent to Trump’s “America First” policy.

She’s supported a hawkish foreign policy toward Islamist terrorist groups but has been notably anti-war toward US adversaries like Russia and Syria, along with her distrust of the US intelligence community’s spying apparatus.

At least part of that fiercely doveish foreign policy appears to be driven by a longstanding conviction that the US is standing on the brink of nuclear war with Russia or China. In 2018, Hawaii residents received an accidentally sent alert on their phones warning of an incoming ballistic missile attack. The warning stemmed from a miscommunication during a state drill, not any action by an American adversary. But for Gabbard, the incident was a “wake-up call” that “the threat of nuclear war was and is real and is even greater today,” she wrote in her memoir.

A consistent theme in Gabbard’s book is that the “Democrat elite and neocons” have formed a “cabal of warmongers in permanent Washington.”

“Politicians have plans in place to protect themselves so they can continue to wage a nuclear war from underground in the event of such an attack,” she wrote.

Those same “warmongers in Washington from both political parties… lie to us about the consequences of their warmongering and where it could lead.”

Current and former intelligence officials say they’re particularly concerned by what they see as an unnerving worldview that appears to give precedence to the views of foreign dictators over American leaders.

In early 2022, Gabbard endorsed Russian President Vladimir Putin’s rationale for the invasion of Ukraine, pinning the blame not on Moscow but on the Biden administration’s failure to acknowledge “Russia’s legitimate security concerns regarding Ukraine’s becoming a member of NATO.”

She also repeated a debunked Russian conspiracy theory about supposed American biolabs in Ukraine developing deadly pathogens.

Her public remarks have drawn attention in Russia, where panelists on a Russian state media television show cynically asked if she was a Kremlin state agent. “Yes!” the host said, without evidence.

Some prominent Republicans like former Trump national security adviser John Bolton and former Trump UN ambassador and 2024 GOP presidential candidate Nikki Haley have come out against her.

“This is not a place for a Russian, Iranian, Syrian, Chinese sympathizer. DNI has to analyze real threats,” Haley said Wednesday on her weekly radio program. “Are we comfortable with someone like that at the top of our national intelligence agencies?”

Gabbard has shown no compunction about courting controversy over her foreign policy ideas — and the uproar over her empathetic posture towards Russia appeared not only to sharpen her turn to the right but harden her suspicions of the intelligence community.

In 2020, former Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton suggested, without evidence, that Russia was “grooming” Gabbard — an accusation that appeared to profoundly offend Gabbard and give her a deep empathy for Trump. In her 2024 memoir, she wrote that Democrats had “invented a conspiracy theory that (Trump) was ‘colluding’ with the Russians to win the election. Hillary Clinton used a similar tactic against me.”

A meeting with Assad that ‘blindsided’ Democrats

Before coming to Washington, Gabbard joined in the Hawaii National Guard and deployed to Iraq in 2004. Her experience during the Iraq War appeared to shape her populist, anti-interventionist worldview in ways that would often put her at odds with the Obama administration — and showcase her willingness to defy her party.

Gabbard was elected to Congress at age 31. She found a natural place on the House Armed Services Committee both as a veteran and a lawmaker representing Hawaii, a state with a significant military presence.

Lawmakers and congressional aides who served with Gabbard on the committee told CNN Gabbard quickly became a “reliable foil” for Democrats on the committee. She was particularly focused on stopping the war in Syria and opposed the Obama administration’s strategy of backing rebel groups against Syrian President al-Bashar Assad. She also opposed US military strikes in in 2014 after ISIS took over large swaths of Syrian territory.

“She was playing on her own team,” said one former committee aide.

In January 2017, Gabbard planned a trip to Lebanon and Syria sponsored by an Ohio-based Arab American economic group. Her original itinerary filed with the House Ethics Committee did not include any meetings with Assad.

But Gabbard met Assad twice during her four days in Syria, according to travel documents she filed with the House after her trip.

Her trip and meetings caught Democrats in Congress completely by surprise, former aides and lawmakers said, as she didn’t inform committee leaders or then-House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi. Former aides said Gabbard’s colleagues were “stunned” and “blindsided” that she would meet with an adversary of the US.

When she returned, Gabbard said in an interview with CNN that she met with Assad because “there has to be a conversation with him” for any viable peace agreement.

“When the opportunity arose to meet with him, I did so because I felt that it’s important that if we profess to truly care about the Syrian people, about their suffering, then we’ve got to be able to meet with anyone that we need to if there is a possibility that we can achieve peace,” she said.

Three months later, Gabbard opposed Trump’s military strikes in Syria in response to a chemical weapons attack. She also criticized Trump’s 2020 killing of Iranian commander Qasem Soleimani, saying after an intelligence briefing that there was “no justification whatsoever for this illegal and unconstitutional act of war that President Trump took.”

‘Accountable to no one’

Gabbard left Congress in January 2021, after not running for reelection while she mounted a longshot Democratic presidential campaign that focused on her anti-war views.

In October 2022, she announced that she was leaving the Democratic Party altogether. By October 2024, Gabbard had endorsed Trump, joined his transition team and officially switched parties.

Gabbard is in many ways a stranger to the intelligence community. Multiple current and former career officials who spoke to CNN were alarmed by some of her more controversial public statements but knew little about her beyond the headlines. As a member of Congress, Gabbard served on the House Armed Services Committee, but has had no formal oversight or work with the community she may be tasked with leading.

Lawmakers who served alongside Gabbard in Congress say that it was often a challenge to figure out where she stood ideologically.

But Gabbard’s disdain for government surveillance powers — and her aggrieved sense that Americans have been lied to about those authorities — are among her most coherent and consistent national security positions, even as Gabbard has transformed from a Democratic congresswoman and presidential candidate to a potential Cabinet member in the new Trump administration.

In 2017, when Trump was challenging the credibility of the FBI’s investigation into his campaign’s ties to Russia, Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer warned him: “You take on the intelligence community, they have six ways from Sunday at getting back at you.”

Gabbard, then a Democrat, heard a “chilling message,” she wrote in her memoir: “The intelligence community and national security state are so supremely powerful and accountable to no one that even the president of the United States better not dare criticize them.”

Tulsi Gabbard, then in the midst of a failed bid for the Democratic nomination for president, met with Daniel Ellsberg, a military analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times and The Washington Post in the 1970s and was charged with violations of the Espionage Act. He argued to her that it should be unconstitutional to charge officials who leak classified information to media outlets with espionage.

Gabbard agreed, declaring the practice “insanity.” Later that year, she introduced a bill in the House called the “Protect Brave Whistleblowers Act,” designed to shield people like Ellsberg. She wrote two more bills that same week supporting Julian Assange and Edward Snowden, who were behind two of the biggest US national security leaks of the 21st Century.

Trump’s selection of Gabbard to run the Office of the Director of National Intelligence has quickly drawn scrutiny because of her relative inexperience in the intelligence community and her public adoption of positions on Syria and the war in Ukraine that many national security officials see as Russian propaganda.

But where she is perhaps most at odds with the agencies she may soon be tasked with leading is her distrust of broad government surveillance authorities and her support for those willing to expose some of the intelligence community’s most sensitive secrets.

It’s also where she may come into conflict with Trump’s own past record — even as she appears to represent an evolution of the MAGA movement toward a more youthful, techno-libertarian vision of the anti-surveillance faction of the Republican Party. It was the first Trump administration, after all, that in 2019 took the unprecedented step of charging Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, with Espionage Act violations for soliciting and publishing classified information.

“Tulsi Gabbard is a highly unusual pick for Director of National Intelligence in an administration that has nominated some very solid people, like Marco Rubio, Elise Stefanik and Mike Waltz, because she’s somebody who clearly thinks that Edward Snowden should get away scot-free from stealing classified information,” said Jamil Jaffer, a former George W. Bush administration associate White House counsel and founder and executive director of the National Security Institute at George Mason University’s law school.

Gabbard has fiercely defended Assange, introducing a bill in 2020 opposing his extradition and prosecution. And her legislation defending Snowden, the contractor who in 2013 revealed the existence of the bulk collection of American phone records by the National Security Agency before fleeing to Russia, called on the federal government to drop all charges.

Both men are broadly seen as enemies of the state within the intelligence community. And the information they have exposed, officials say, has done grievous harm to America’s ability to collect and protect intelligence.

But both are also causes that have drawn a curious cross-section of political support, from the far left — Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has also opposed the extradition of Assange — to the libertarian-leaning right that contains both Trump allies like Sen. Rand Paul as well as critics such as former Rep. Justin Amash. Former Rep. Matt Gaetz, Trump’s pick to be attorney general, was one of two lawmakers to co-sponsor of Gabbard’s Snowden legislation.

It’s an unusual coalition that long predates — and in some ways exists outside of — Trump’s own deep skepticism of the “deep state” intelligence community, fueled by his claims that the FBI and other intelligence agencies illegally surveilled him as part of a political witch hunt.

Since arriving in Washington roughly a dozen years ago, Gabbard has evolved from a Democratic congresswoman who ran for president in 2020 to a Trump-endorsing Fox News regular who defected to the Republican Party earlier this year.

Interviews with former lawmakers and congressional aides who served with Gabbard as well as a reading of her 2024 memoir highlight a political chameleon who has maintained a populist and isolationist worldview, a willingness to buck party orthodoxy and a tendency to distrust authority figures that her critics say veers into outright conspiracy theory.

“People have core values and beliefs, and Tulsi, I believe, kind of lacks that,” said one Democrat who was close to Gabbard while they were in Congress together.

Gabbard did not respond to CNN’s request for an interview. Trump in a statement announcing her selection said Gabbard would bring a “fearless spirit that has defined her illustrious career to our Intelligence Community, championing our Constitutional Rights, and securing Peace through Strength.”

Gabbard proposed repealing Patriot Act

If confirmed, Gabbard will be the most markedly anti-surveillance official to lead the intelligence community in the post-9/11 era. Her animus towards what she has described as the “national security state and its warmongering friends,” hellbent on using the Espionage Act and other tools to punish its enemies, raises questions about whether she might seek to reshape the rules by which American intelligence agencies have been collecting, searching and using intelligence for decades.

In December 2020, shortly before she left Congress, Gabbard introduced legislation that would repeal the Patriot Act and Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, two of the most significant surveillance authorities passed by Congress after September 11, 2001. Like her other legislative attempts on spying issues, it went nowhere.

The DNI’s primary responsibility — beyond his or her role in determining what intelligence the president sees every day in his daily brief — is over the budget and priorities of the 18 agencies that make up the intelligence community. Because of that, it would be a complicated and difficult — though not impossible — task for Gabbard to unilaterally dismantle intelligence collection under Section 702.

In theory, Gabbard could issue an order to the intelligence community not to use 702 at all, but the Defense Department and Congress would likely push back on that, said Glenn Gerstell, former general counsel at the National Security Agency.

Getting rid of Section 702 entirely would address Gabbard’s concern — shared by civil liberties advocates in both parties — that the law offers too many ways for the intelligence community to surveil Americans without a warrant. But it would also dramatically curtail America’s ability to spy on foreign adversaries overseas, Gerstell said.

“If you were to eliminate just that one statute, you could take about 60% or 70% of the pages of (the president’s daily brief) and just throw it out before it even gets to the commander in chief,” Gerstell said. “And I can’t imagine why any commander in chief would want to operate in this world blindfolded.”

Fighting against a ‘cabal of warmongers’

As both a Democrat and a Republican, Gabbard has espoused a firmly isolationist, anti-war ideology — an organizing principle that fit her identity both as an up-and-coming progressive star and then, later, an adherent to Trump’s “America First” policy.

She’s supported a hawkish foreign policy toward Islamist terrorist groups but has been notably anti-war toward US adversaries like Russia and Syria, along with her distrust of the US intelligence community’s spying apparatus.

At least part of that fiercely doveish foreign policy appears to be driven by a longstanding conviction that the US is standing on the brink of nuclear war with Russia or China. In 2018, Hawaii residents received an accidentally sent alert on their phones warning of an incoming ballistic missile attack. The warning stemmed from a miscommunication during a state drill, not any action by an American adversary. But for Gabbard, the incident was a “wake-up call” that “the threat of nuclear war was and is real and is even greater today,” she wrote in her memoir.

A consistent theme in Gabbard’s book is that the “Democrat elite and neocons” have formed a “cabal of warmongers in permanent Washington.”

“Politicians have plans in place to protect themselves so they can continue to wage a nuclear war from underground in the event of such an attack,” she wrote.

Those same “warmongers in Washington from both political parties… lie to us about the consequences of their warmongering and where it could lead.”

Current and former intelligence officials say they’re particularly concerned by what they see as an unnerving worldview that appears to give precedence to the views of foreign dictators over American leaders.

In early 2022, Gabbard endorsed Russian President Vladimir Putin’s rationale for the invasion of Ukraine, pinning the blame not on Moscow but on the Biden administration’s failure to acknowledge “Russia’s legitimate security concerns regarding Ukraine’s becoming a member of NATO.”

She also repeated a debunked Russian conspiracy theory about supposed American biolabs in Ukraine developing deadly pathogens.

Her public remarks have drawn attention in Russia, where panelists on a Russian state media television show cynically asked if she was a Kremlin state agent. “Yes!” the host said, without evidence.

Some prominent Republicans like former Trump national security adviser John Bolton and former Trump UN ambassador and 2024 GOP presidential candidate Nikki Haley have come out against her.

“This is not a place for a Russian, Iranian, Syrian, Chinese sympathizer. DNI has to analyze real threats,” Haley said Wednesday on her weekly radio program. “Are we comfortable with someone like that at the top of our national intelligence agencies?”

Gabbard has shown no compunction about courting controversy over her foreign policy ideas — and the uproar over her empathetic posture towards Russia appeared not only to sharpen her turn to the right but harden her suspicions of the intelligence community.

In 2020, former Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton suggested, without evidence, that Russia was “grooming” Gabbard — an accusation that appeared to profoundly offend Gabbard and give her a deep empathy for Trump. In her 2024 memoir, she wrote that Democrats had “invented a conspiracy theory that (Trump) was ‘colluding’ with the Russians to win the election. Hillary Clinton used a similar tactic against me.”

A meeting with Assad that ‘blindsided’ Democrats

Before coming to Washington, Gabbard joined in the Hawaii National Guard and deployed to Iraq in 2004. Her experience during the Iraq War appeared to shape her populist, anti-interventionist worldview in ways that would often put her at odds with the Obama administration — and showcase her willingness to defy her party.

Gabbard was elected to Congress at age 31. She found a natural place on the House Armed Services Committee both as a veteran and a lawmaker representing Hawaii, a state with a significant military presence.

Lawmakers and congressional aides who served with Gabbard on the committee told CNN Gabbard quickly became a “reliable foil” for Democrats on the committee. She was particularly focused on stopping the war in Syria and opposed the Obama administration’s strategy of backing rebel groups against Syrian President al-Bashar Assad. She also opposed US military strikes in in 2014 after ISIS took over large swaths of Syrian territory.

“She was playing on her own team,” said one former committee aide.

In January 2017, Gabbard planned a trip to Lebanon and Syria sponsored by an Ohio-based Arab American economic group. Her original itinerary filed with the House Ethics Committee did not include any meetings with Assad.

But Gabbard met Assad twice during her four days in Syria, according to travel documents she filed with the House after her trip.

Her trip and meetings caught Democrats in Congress completely by surprise, former aides and lawmakers said, as she didn’t inform committee leaders or then-House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi. Former aides said Gabbard’s colleagues were “stunned” and “blindsided” that she would meet with an adversary of the US.

When she returned, Gabbard said in an interview with CNN that she met with Assad because “there has to be a conversation with him” for any viable peace agreement.

“When the opportunity arose to meet with him, I did so because I felt that it’s important that if we profess to truly care about the Syrian people, about their suffering, then we’ve got to be able to meet with anyone that we need to if there is a possibility that we can achieve peace,” she said.

Three months later, Gabbard opposed Trump’s military strikes in Syria in response to a chemical weapons attack. She also criticized Trump’s 2020 killing of Iranian commander Qasem Soleimani, saying after an intelligence briefing that there was “no justification whatsoever for this illegal and unconstitutional act of war that President Trump took.”

‘Accountable to no one’

Gabbard left Congress in January 2021, after not running for reelection while she mounted a longshot Democratic presidential campaign that focused on her anti-war views.

In October 2022, she announced that she was leaving the Democratic Party altogether. By October 2024, Gabbard had endorsed Trump, joined his transition team and officially switched parties.

Gabbard is in many ways a stranger to the intelligence community. Multiple current and former career officials who spoke to CNN were alarmed by some of her more controversial public statements but knew little about her beyond the headlines. As a member of Congress, Gabbard served on the House Armed Services Committee, but has had no formal oversight or work with the community she may be tasked with leading.

Lawmakers who served alongside Gabbard in Congress say that it was often a challenge to figure out where she stood ideologically.

But Gabbard’s disdain for government surveillance powers — and her aggrieved sense that Americans have been lied to about those authorities — are among her most coherent and consistent national security positions, even as Gabbard has transformed from a Democratic congresswoman and presidential candidate to a potential Cabinet member in the new Trump administration.

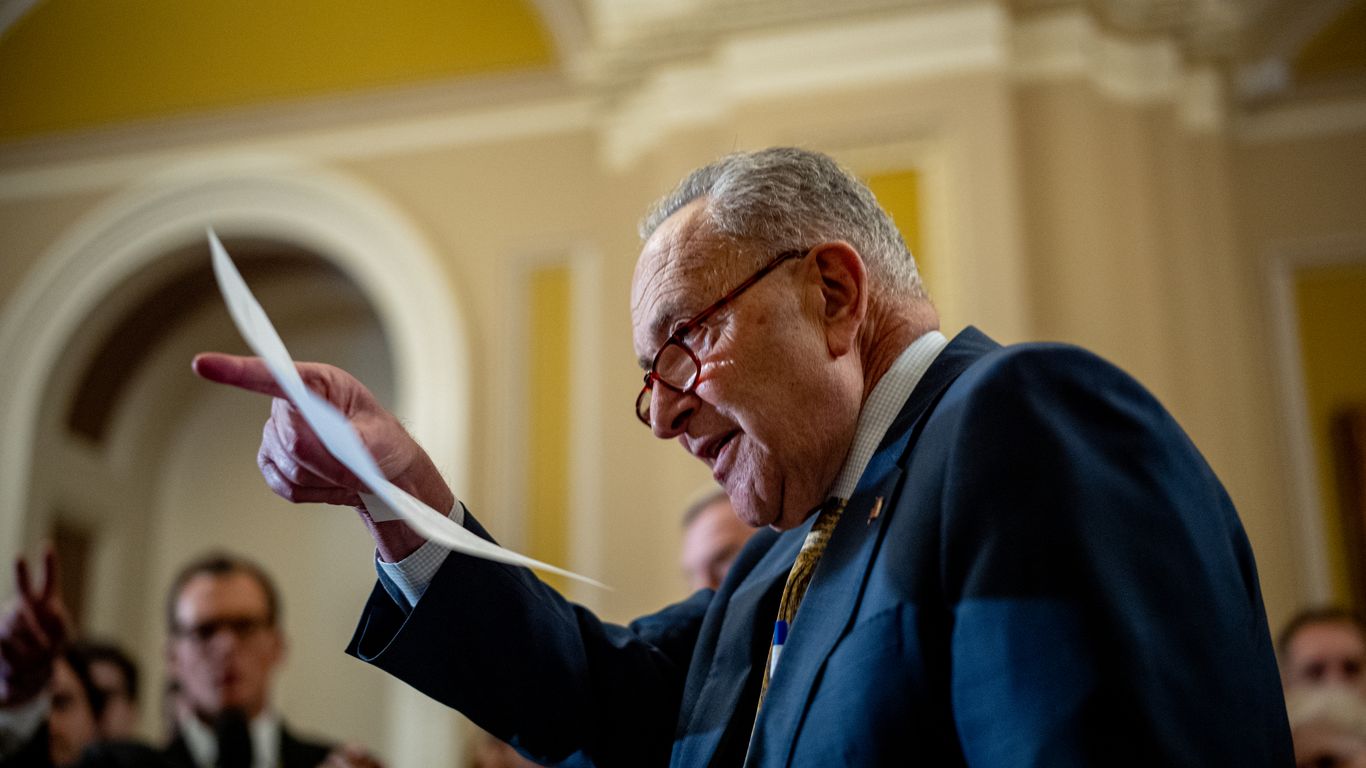

In 2017, when Trump was challenging the credibility of the FBI’s investigation into his campaign’s ties to Russia, Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer warned him: “You take on the intelligence community, they have six ways from Sunday at getting back at you.”

Gabbard, then a Democrat, heard a “chilling message,” she wrote in her memoir: “The intelligence community and national security state are so supremely powerful and accountable to no one that even the president of the United States better not dare criticize them.”

Comments( 0 )

0 0 3