Susan Smith case: 2 boys drowned and a deception that gripped the nation: Why it is still intensely felt 30 years later

Posted on 11/21/2024

Inside Susan Smith’s car pulled from the bottom of a South Carolina lake in 1994 were the bodies of her two young boys, still strapped in their car seats, along with her wedding dress and photo album.

Everything that symbolized Smith’s life was in that car, investigators say, except for her husband who stood beside her on the national stage for nine days as she lied, describing a fictional carjacker and pleading for the return of her children – Michael, 3, and Alex, 14 months – who were already dead.

Over 30 years later, an emotional Smith, now 53 and eligible for parole, was heard on Wednesday pleading again, this time for her own mercy. Smith was unanimously denied parole by the board after her ex-husband David Smith and 14 other witnesses gave emotional statements opposing her release, making her chances for parole all but impossible, experts told CNN.

The case set off a media firestorm and dayslong manhunt for a suspect after Smith, then 23, told police in November 1994 her sons were taken when she was carjacked by a Black man in the city of Union, in late October. The false accusation took flight as people across the country searched for the boys, setting up vigils, hanging flyers and calling police with tips.

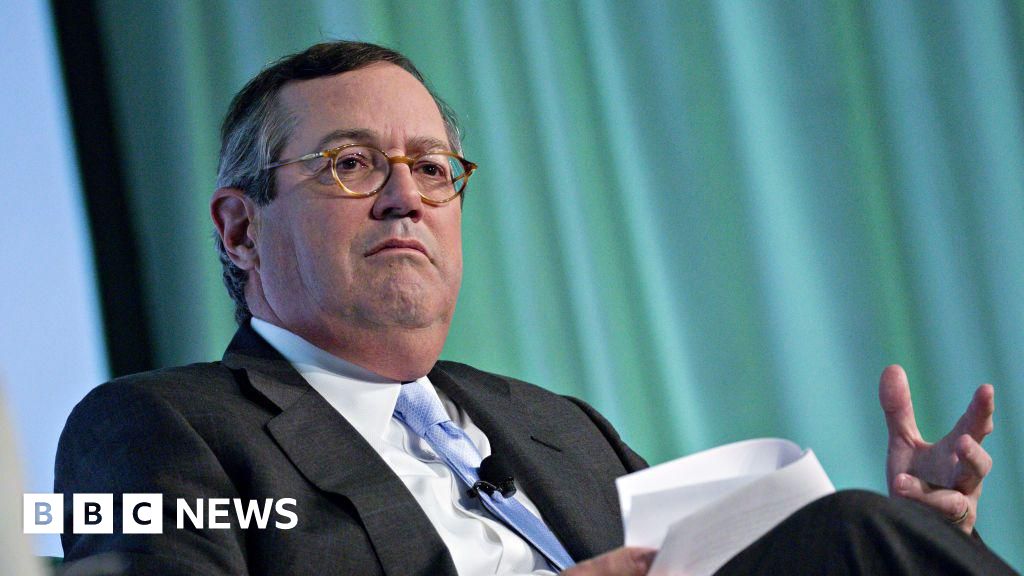

“When that car is pulled out and in those two car seats are two precious boys who have been in the water for nine days … I saw men and women in law enforcement just crying,” said Tommy Pope, the lead prosecutor on the case who was there when the car was lifted from John D. Long Lake.

“The betrayal was worse than had there been a carjacker, and that’s what’s made it resonate through the decades now – people were so drawn in to help and drawn in by Susan,” Pope told CNN.

The loss of Michael and Alex and the betrayal so deeply felt by all of those who clung to every hope that the boys would be found – investigators and family alike – still reverberates through the community. Smith’s generic description of a Black man as the suspect fits into the racist phenomenon of White women falsely accusing Black men of being criminals, which has permeated society for decades, said Gloria Browne-Marshall, civil rights attorney and law professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

“How many Black men were detained, beaten, arrested, accused of this crime based on the notion of her word alone?” Browne-Marshall said.

Investigators were skeptical of Smith’s story from the start, and eventually, under questioning, she confessed to rolling her car into the lake, killing her sons.

At her 1995 murder trial, which was followed closely around the world, the prosecution pointed to reports Smith was having an affair with her boss’ rich son who had just broken up with her because he didn’t want children. Smith’s attorneys argued she was suicidal and depressed and intended to stay in the car with her children, claiming it was a botched murder-suicide.

That argument didn’t add up, Pope said, when law enforcement tested the car to determine if Smith had a chance to change her mind or save her children after she rolled her car into the lake.

Investigators determined the car floated for about six minutes before it sunk below the water surface and to the bottom of the lake with her boys inside.

“This wasn’t a tragic mistake,” David Smith said at Wednesday’s hearing. “She purposely meant to end their lives. I never have felt any remorse from her. She never expressed any to me.”

‘I know that what I did was horrible’

Pope, a former 16th Judicial Circuit solicitor who worked in state law enforcement for years before becoming a prosecutor, believes Smith was trying to wipe away every trace of her life.

Smith in the ’90s worked at a local textile mill with a man believed to have been her lover, Pope said. But when Smith received his breakup letter, she took it to heart, he said.

“Susan Smith made a horrible decision that, somehow, if she didn’t have kids, that she was going to somehow be with this guy that was really just blowing her off,” Pope said. “She had convinced herself, based on what he wrote, that somehow, she would be with him.”

“She basically packed up that whole part of her life and put it in that lake,” Pope said.

Pope had sought the death penalty for Smith, he said, but the jury opted to give her a life sentence, believing the harsher punishment for her was serving a life sentence so she could reflect on her actions.

But Pope said he doesn’t believe this has been the case, pointing to her internal disciplinary charges during her three decades in prison.

Smith testified on her own behalf Wednesday, pleading for her release via video before the South Carolina Board of Paroles and Pardons in Columbia and saying she had learned from her mistakes.

“I know that what I did was horrible,” Smith tearfully told the board.

At the hearing, David Smith pointed to his ex-wife’s record as he told the parole board that 30 years is simply not enough time for Susan Smith to spend in prison.

“I’m not here to speak about what she’s done in prison… I’m just here to advocate on Michael’s and Alex’s behalf and as their father,” he said.

The father said he questioned whether he could go on after Susan Smith killed their sons.

“What she did not only to Michael and Alex, she came pretty close to causing me to end my life because of the grief she brought upon me,” David Smith said.

Susan Smith’s attorney, Tommy A. Thomas, did not respond to a request for comment before or after Wednesday’s parole hearing. He told the board his client was “truly remorseful.”

Hundreds opposed Smith’s parole

Smith’s chances for parole were already unlikely, as research shows the main factor influencing parole decisions is the presence of a victim or the victim’s family, said Hayden Smith, professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of South Carolina.

Her disciplinary record and the media attention involved also likely played a role in the outcome, he said.

But the presence of her former husband and 14 witnesses at the hearing who opposed Susan Smith’s parole made her chances “next to none,” the professor said.

“Victims showing up, making statements – that’s the central part of this, the dynamic that happens in the room – that relationship. The parole board really listens to that,” said Hayden Smith, who conducts research for the state’s department of corrections and has interviewed Susan Smith while incarcerated.

As of the first week of November, the Office of Victim Services had received at least 360 letters, emails and messages about Smith’s parole hearing, with all but six opposing granting her parole, the department said.

Parole is granted only for violent offenders about 8% of the time, according to the South Carolina Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services.

Violent crime offenders who are released on parole put pressure on a system already strapped for resources, the professor said.

“In Susan’s case, she was incarcerated for a long period of time. You often have mental health issues, housing issues, victim notification and a whole range of sanctions,” said Hayden Smith, describing the parole process after release.

It goes back, he said, to the 1988 case of convicted murderer Willie Horton, who raped a woman and stabbed her partner while furloughed from prison under a Massachusetts program.

“That’s the Willie Horton rule, which is, can you give me some assurances as the parole board that this person is not going to hurt someone?” said Hayden Smith.

A history of Black men being falsely accused

Susan Smith’s case is the “quintessential mix of southern ingredients,” said professor Smith – emphasizing the racial undertones of the case.

“What was the effect of some people in the community instantly assuming her story was correct and starting to pursue and look around for African Americans?” the professor said.

Professor Browne-Marshall says the case reflects an over 150-year history of White women making false accusations about Black men with the assumption society will “buy into the notion of innate hostility that Black people have in their DNA, which is a myth, as well as the lust they supposedly have for White women.”

Browne-Marshall referenced the work of Black journalist Ida B. Wells, who investigated lynchings in Southern states, saying many lynchings involved White women making accusations against Black men, but some “didn’t even involve White women.”

That societal phenomenon, the professor said, is a “demonstrated position of power that White women have.”

“The very notion was enough to trigger someone to say that whoever has been accused must have done it. So, it’s not a question about whether or not this person is lying, it’s a question of which Black man did it,” she continued. “… It’s a historical power play that still works today.”

After Smith’s confession, her family apologized to the Black community, with her brother issuing a statement saying “it is really disturbing to think that this would be a racial issue,” according to a November 1994 report in the Washington Post.

Pope says he’s still haunted by the thought that an innocent Black man could have ended up in jail because of the false accusation. If that happened, Pope said he would have quit his job.

“Susan’s description was so generic, if she had stuck with it and tried to identify somebody … It’s terrifying to think if she had really named somebody,” the prosecutor said. “I’d have never gotten over it if that had occurred.”

In the nine days that Susan Smith repeated her lie again and again, often sobbing and appearing emotionally distraught on camera, Pope believes one media interview – in retrospect – revealed a likely truth.

“She talks about when the carjacker is driving away and her kids are crying for her. I’m thinking, ‘well, that part was probably true. She’s rolled them in the lake and they’re floating, screaming for their mama for six minutes,” said Pope.

“Some of the best lies are wrapped in truth.”

Everything that symbolized Smith’s life was in that car, investigators say, except for her husband who stood beside her on the national stage for nine days as she lied, describing a fictional carjacker and pleading for the return of her children – Michael, 3, and Alex, 14 months – who were already dead.

Over 30 years later, an emotional Smith, now 53 and eligible for parole, was heard on Wednesday pleading again, this time for her own mercy. Smith was unanimously denied parole by the board after her ex-husband David Smith and 14 other witnesses gave emotional statements opposing her release, making her chances for parole all but impossible, experts told CNN.

The case set off a media firestorm and dayslong manhunt for a suspect after Smith, then 23, told police in November 1994 her sons were taken when she was carjacked by a Black man in the city of Union, in late October. The false accusation took flight as people across the country searched for the boys, setting up vigils, hanging flyers and calling police with tips.

“When that car is pulled out and in those two car seats are two precious boys who have been in the water for nine days … I saw men and women in law enforcement just crying,” said Tommy Pope, the lead prosecutor on the case who was there when the car was lifted from John D. Long Lake.

“The betrayal was worse than had there been a carjacker, and that’s what’s made it resonate through the decades now – people were so drawn in to help and drawn in by Susan,” Pope told CNN.

The loss of Michael and Alex and the betrayal so deeply felt by all of those who clung to every hope that the boys would be found – investigators and family alike – still reverberates through the community. Smith’s generic description of a Black man as the suspect fits into the racist phenomenon of White women falsely accusing Black men of being criminals, which has permeated society for decades, said Gloria Browne-Marshall, civil rights attorney and law professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

“How many Black men were detained, beaten, arrested, accused of this crime based on the notion of her word alone?” Browne-Marshall said.

Investigators were skeptical of Smith’s story from the start, and eventually, under questioning, she confessed to rolling her car into the lake, killing her sons.

At her 1995 murder trial, which was followed closely around the world, the prosecution pointed to reports Smith was having an affair with her boss’ rich son who had just broken up with her because he didn’t want children. Smith’s attorneys argued she was suicidal and depressed and intended to stay in the car with her children, claiming it was a botched murder-suicide.

That argument didn’t add up, Pope said, when law enforcement tested the car to determine if Smith had a chance to change her mind or save her children after she rolled her car into the lake.

Investigators determined the car floated for about six minutes before it sunk below the water surface and to the bottom of the lake with her boys inside.

“This wasn’t a tragic mistake,” David Smith said at Wednesday’s hearing. “She purposely meant to end their lives. I never have felt any remorse from her. She never expressed any to me.”

‘I know that what I did was horrible’

Pope, a former 16th Judicial Circuit solicitor who worked in state law enforcement for years before becoming a prosecutor, believes Smith was trying to wipe away every trace of her life.

Smith in the ’90s worked at a local textile mill with a man believed to have been her lover, Pope said. But when Smith received his breakup letter, she took it to heart, he said.

“Susan Smith made a horrible decision that, somehow, if she didn’t have kids, that she was going to somehow be with this guy that was really just blowing her off,” Pope said. “She had convinced herself, based on what he wrote, that somehow, she would be with him.”

“She basically packed up that whole part of her life and put it in that lake,” Pope said.

Pope had sought the death penalty for Smith, he said, but the jury opted to give her a life sentence, believing the harsher punishment for her was serving a life sentence so she could reflect on her actions.

But Pope said he doesn’t believe this has been the case, pointing to her internal disciplinary charges during her three decades in prison.

Smith testified on her own behalf Wednesday, pleading for her release via video before the South Carolina Board of Paroles and Pardons in Columbia and saying she had learned from her mistakes.

“I know that what I did was horrible,” Smith tearfully told the board.

At the hearing, David Smith pointed to his ex-wife’s record as he told the parole board that 30 years is simply not enough time for Susan Smith to spend in prison.

“I’m not here to speak about what she’s done in prison… I’m just here to advocate on Michael’s and Alex’s behalf and as their father,” he said.

The father said he questioned whether he could go on after Susan Smith killed their sons.

“What she did not only to Michael and Alex, she came pretty close to causing me to end my life because of the grief she brought upon me,” David Smith said.

Susan Smith’s attorney, Tommy A. Thomas, did not respond to a request for comment before or after Wednesday’s parole hearing. He told the board his client was “truly remorseful.”

Hundreds opposed Smith’s parole

Smith’s chances for parole were already unlikely, as research shows the main factor influencing parole decisions is the presence of a victim or the victim’s family, said Hayden Smith, professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of South Carolina.

Her disciplinary record and the media attention involved also likely played a role in the outcome, he said.

But the presence of her former husband and 14 witnesses at the hearing who opposed Susan Smith’s parole made her chances “next to none,” the professor said.

“Victims showing up, making statements – that’s the central part of this, the dynamic that happens in the room – that relationship. The parole board really listens to that,” said Hayden Smith, who conducts research for the state’s department of corrections and has interviewed Susan Smith while incarcerated.

As of the first week of November, the Office of Victim Services had received at least 360 letters, emails and messages about Smith’s parole hearing, with all but six opposing granting her parole, the department said.

Parole is granted only for violent offenders about 8% of the time, according to the South Carolina Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services.

Violent crime offenders who are released on parole put pressure on a system already strapped for resources, the professor said.

“In Susan’s case, she was incarcerated for a long period of time. You often have mental health issues, housing issues, victim notification and a whole range of sanctions,” said Hayden Smith, describing the parole process after release.

It goes back, he said, to the 1988 case of convicted murderer Willie Horton, who raped a woman and stabbed her partner while furloughed from prison under a Massachusetts program.

“That’s the Willie Horton rule, which is, can you give me some assurances as the parole board that this person is not going to hurt someone?” said Hayden Smith.

A history of Black men being falsely accused

Susan Smith’s case is the “quintessential mix of southern ingredients,” said professor Smith – emphasizing the racial undertones of the case.

“What was the effect of some people in the community instantly assuming her story was correct and starting to pursue and look around for African Americans?” the professor said.

Professor Browne-Marshall says the case reflects an over 150-year history of White women making false accusations about Black men with the assumption society will “buy into the notion of innate hostility that Black people have in their DNA, which is a myth, as well as the lust they supposedly have for White women.”

Browne-Marshall referenced the work of Black journalist Ida B. Wells, who investigated lynchings in Southern states, saying many lynchings involved White women making accusations against Black men, but some “didn’t even involve White women.”

That societal phenomenon, the professor said, is a “demonstrated position of power that White women have.”

“The very notion was enough to trigger someone to say that whoever has been accused must have done it. So, it’s not a question about whether or not this person is lying, it’s a question of which Black man did it,” she continued. “… It’s a historical power play that still works today.”

After Smith’s confession, her family apologized to the Black community, with her brother issuing a statement saying “it is really disturbing to think that this would be a racial issue,” according to a November 1994 report in the Washington Post.

Pope says he’s still haunted by the thought that an innocent Black man could have ended up in jail because of the false accusation. If that happened, Pope said he would have quit his job.

“Susan’s description was so generic, if she had stuck with it and tried to identify somebody … It’s terrifying to think if she had really named somebody,” the prosecutor said. “I’d have never gotten over it if that had occurred.”

In the nine days that Susan Smith repeated her lie again and again, often sobbing and appearing emotionally distraught on camera, Pope believes one media interview – in retrospect – revealed a likely truth.

“She talks about when the carjacker is driving away and her kids are crying for her. I’m thinking, ‘well, that part was probably true. She’s rolled them in the lake and they’re floating, screaming for their mama for six minutes,” said Pope.

“Some of the best lies are wrapped in truth.”

Comments( 0 )

0 0 4

0 0 2

0 0 2

0 0 3