Trump Transition Updates: House Speaker Doesn’t Want Gaetz Ethics Report Released

Posted on 11/16/2024

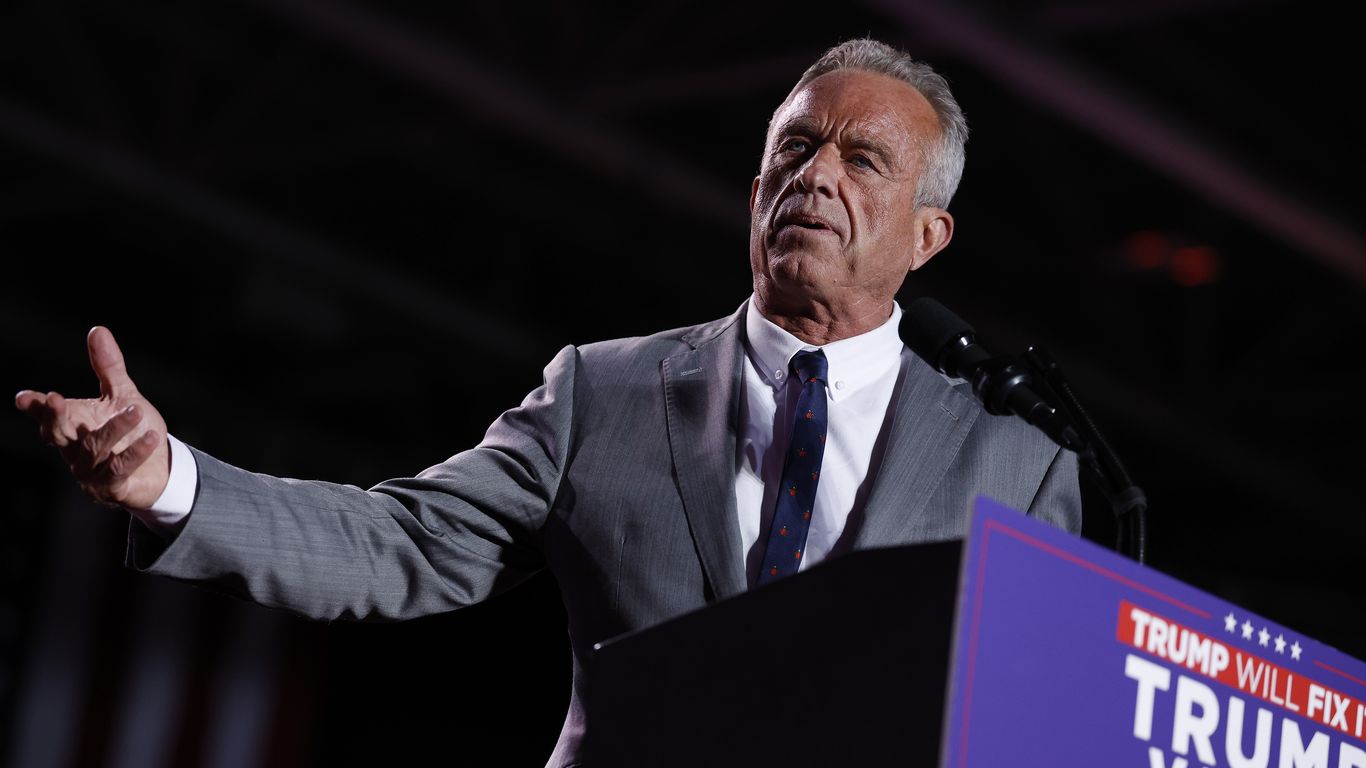

Whatever one calls him, Mr. Kennedy is a polarizing choice whose views on certain public health matters beyond vaccination are far outside the mainstream. He opposes fluoride in water. He favors raw milk, which the Food and Drug Administration deems risky. And he has promoted unproven therapies like hydroxychloroquine for Covid-19. His own relatives called his presidential bid “dangerous for our country.”

If there is a through line to Mr. Kennedy’s thinking, it appears to be a deep mistrust of corporate influence on health and medicine. In some cases, that has led him to support positions that are also embraced by public health professionals, including his push to get ultra-processed foods, which have been linked to obesity, off grocery store shelves. His disdain for profit-seeking pharmaceutical manufacturers and food companies drew applause on the campaign trail.

People close to him say his commitment to “make America healthy again” is heartfelt.

“This is his life’s mission,” said Brian Festa, a founder of We the Patriots U.S.A., a “medical freedom” group that has pushed back on vaccine mandates, who said he has known Mr. Kennedy for years.

But like Mr. Trump, Mr. Kennedy also has a tendency to float wild theories based on scanty evidence. And he has hinted at taking actions, like prosecuting leading medical journals, that have unnerved the medical community. On Friday, many leading public health experts reacted to his nomination with alarm.

“This is the first time we’ve ever had someone that walking in the door whose public views, you just can’t trust,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, the executive director of the American Public Health Association, which represents 25,000 public health professionals.

He called Mr. Kennedy, an environmental lawyer, “totally unprepared, by skill and by training,” for the job of secretary, which involves managing a department with more than 80,000 employees and 13 operating divisions, overseeing everything from Medicare to biomedical research.

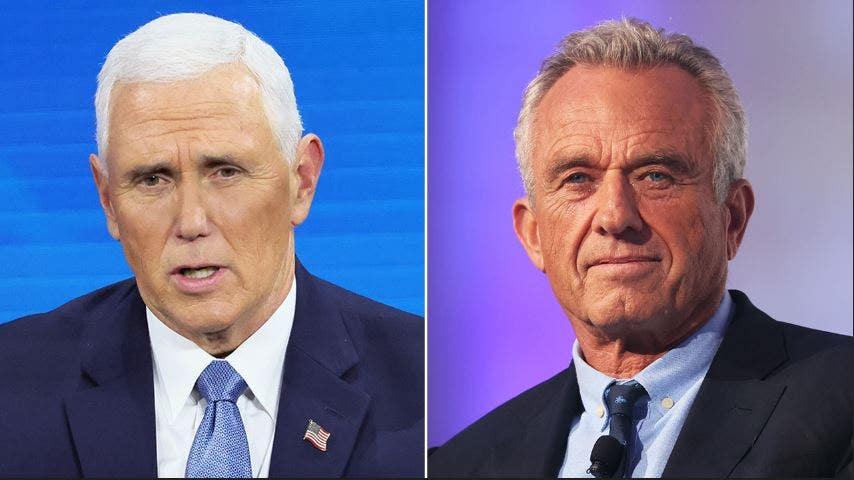

Mike Pence, the former vice president under Mr. Trump, publicly opposed Mr. Kennedy’s nomination on Friday, citing his support for abortion rights.

The pharmaceutical industry’s trade group issued a statement neither praising nor criticizing Mr. Kennedy’s nomination. Calling itself “a crown jewel of the American economy,” the group vowed to “work with the Trump administration to further strengthen our innovation ecosystem and improve health care for patients.” Shares of stock in vaccine makers fell after Mr. Trump announced his selection of Mr. Kennedy on Thursday.

Mr. Kennedy did not respond to a request for an interview, and he has not publicly outlined his priorities. But if he is confirmed by the Senate, he would have wide latitude as health secretary, and has forecast his plans to shake things up.

In an interview in January 2024 with Dr. Mark Hyman, before he suspended his own independent presidential campaign and endorsed Mr. Trump, he spoke about what he would do if elected, outlining some of his lesser-known goals.

He said he would steer the nearly $48 billion annual budget of the National Institutes of Health away from drug development and toward studies that would explain high rates of chronic disease. He also said he would seek to prosecute medical journals like The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine under the federal anti-corruption statute.

“I’m going to litigate against you under the racketeering laws, under the general tort laws,” he said during the interview. “I’m going to find a way to sue you unless you come up with a plan right now to show how you’re going to start publishing real science and stop retracting the real science and publishing the fake pharmaceutical science by these phony industry mercenaries, scientists.”

More recently, Mr. Kennedy has said Mr. Trump would advise communities to stop fluoridating their water, contradicting the advice of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which cites fluoridation to reduce tooth decay as on of the ten great public health achievements of the 20th century. He has said he would slash 600 jobs at the N.I.H. and has instructed Food and Drug Administration officials to “preserve your records” and “pack your bags.”

Mr. Kennedy has argued that the F.D.A. is a victim of “corporate capture.” Under a three-decade-old “user fee” program, drug, device and biotech companies make payments to the agency partly to seek product approvals. The fees now account for nearly half the F.D.A.’s budget.

“The F.D.A. is just a sock puppet to the industries it is supposed to regulate,” Mr. Kennedy said in the interview with Dr. Hyman. “All of this is easily changed. I’m not saying I’m going to be able to accomplish it all on Day 1, but I’m going to accomplish it very quickly.”

Public health experts typically focus on Mr. Kennedy’s views on vaccination. Mr. Kennedy has cast doubt on Covid vaccines and has promoted the long-debunked theory that vaccines cause autism. His detractors say that his critiques of vaccine safety have cost lives, pointing in particular to a visit Mr. Kennedy made to Samoa in 2019.

That year, the island nation put its measles vaccination program on hold after the death of two infants who had received measles shots. Mr. Kennedy visited and, according to news reports, met with a prominent vaccine opponent, giving a boost to the anti-vaccination movement there.

The deaths were subsequently attributed to a mistake by the nurses who administered the vaccine, not to the vaccine itself. But the dip in vaccination rates led to a measles outbreak and 83 deaths.

Dr. Jonathan E. Howard, an associate professor of neurology and psychiatry at New York University who has been tracking the anti-vaccine movement for the past 15 years, said Mr. Kennedy would be “a disaster” as health secretary, adding, “He is an anti-vaccine paranoid crank who has a trail of dead children in Samoa.”

Often, Mr. Kennedy uses a “we don’t know” construction to spin out unproven theories, such as his suggestion that the coronavirus might have been engineered to attack specific races.

“Covid-19 is targeted to attack Caucasians and Black people,” Mr. Kennedy said at a fund-raiser, according to The New York Post. “The people who are most immune are Ashkenazi Jews and Chinese.”

“We don’t know whether it was deliberately targeted or not, but there are papers out there that show the racial or ethnic differential and impact,” he added.

Mr. Kennedy was apparently referring to a 2020 study looking at genetic differences in Covid-19 patients, but numerous studies examining racial disparities attribute them to socioeconomic factors, including poverty and lack of access to health care.

Mr. Kennedy also has repeatedly suggested that chemicals in the water might be responsible for “sexual dysphoria” in children. In a clip aired by CNN, he noted that atrazine, a herbicide sometimes found in well water in agricultural areas, will “concentrate and forcibly feminize” frogs. He went on, “What this does to sexual development in children, nobody knows.”

There is no evidence that the chemical, typically used on farms to kill weeds, causes the same effects in children, although studies show it has been linked to birth defects in babies whose mothers are exposed to it. But according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, an arm of the C.D.C., “Most people are not exposed to atrazine on a regular basis.”

Mr. Kennedy came to health advocacy through his work as an environmental lawyer. In 1999, he was named a hero of the planet by Time magazine for his work with the Riverkeeper organization, among the groups credited with cleaning up New York’s polluted Hudson River. One of his aims was to get mercury out of waterways.

In a speech last year at Hillsdale College, he said that in 2005, when he was giving speeches around the country, mothers of children with autism approached him to ask him to take a look at vaccines, some of which had in the past contained a mercury-based preservative, thimerosal. The preservative was removed by manufacturers in 2001 at the request of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and subsequent studies showed no link between the preservative and autism.

In the years since, Mr. Kennedy has made millions of dollars railing against vaccines. The windfall has come through books, including one denigrating Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the former government scientist both celebrated and despised for his work on Covid, and through Children’s Health Defense, the nonprofit he has used as a platform to sow doubts about vaccination.

Allies of Mr. Kennedy say he has earned the right to make policy, given the support he generated while campaigning alongside Mr. Trump. Calley Means, a health care entrepreneur who has been an adviser to Mr. Kennedy and who was instrumental in connecting him to Mr. Trump, said in an interview last week that Mr. Kennedy had “a true mandate to take on broken health care institutions, and to deliver the change.”

Now, after fighting for Mr. Trump in case after case that they helped turn into a form of political theater, some of those lawyers are being rewarded again for their work. Mr. Trump has said he intends to nominate them to high-ranking posts in the Justice Department, which he has made clear he wants to operate as a legal arm of the White House rather than with the quasi-independence that has been the post-Watergate norm.

After the president-elect’s announcement this week that he wants Matt Gaetz, the controversial former Florida congressman and a longtime ally, to be his attorney general, he named Todd Blanche and Emil Bove, two experienced former federal prosecutors who took the lead in defending Mr. Trump at his state trial in Manhattan and against two federal indictments, to fill the No. 2 and No. 3 positions in the department.

A third lawyer, D. John Sauer, who was the Missouri solicitor general and oversaw Mr. Trump’s appellate battles, was chosen to represent the department in front of the Supreme Court as the U.S. solicitor general.

Another lawyer, Stanley Woodward Jr., who defended several people in Mr. Trump’s orbit and helped in the process of vetting his vice-presidential pick, has also been mentioned for a top legal job, though it remains unclear if he will actually receive a role.

Throughout American history, presidents have made a habit of installing lawyers close to them in powerful positions. George Washington picked his personal lawyer, Edmund Randolph, as his first attorney general, and John F. Kennedy put his brother Robert in the post.

But until now, no president had ever nominated his own criminal defense team to top jobs in the Justice Department. And Mr. Trump’s choice of Mr. Blanche, Mr. Bove and Mr. Sauer runs the risk of turning the agency into something it was never meant to be: the president’s private law firm.

“It’s a strange move, for sure, although that’s not to say that you can’t be Trump’s defense lawyer and still be a good lawyer,” said Alan Rozenshtein, a former Justice Department official who teaches at the University of Minnesota Law School. “Still, it raises all sorts of complex conflicts of interest and raises questions about whether the Justice Department should exist to protect the president of the United States.”

At the same time, there has never been a president who entered office having experienced a criminal trial, and three other indictments in different places.

Mr. Trump’s transition office did not respond to an email seeking comment.

When Mr. Trump first came under investigation after he left office, he had a hard time finding — and keeping — lawyers to defend him.

Two of his original lawyers, James Trusty and John Rowley, stepped down from the job shortly after he was indicted in Florida in June 2023 on charges of mishandling classified documents. The month before the indictment was issued, another lawyer, Timothy Parlatore, also quit the team, citing problems with Mr. Trump’s adviser Boris Epshteyn.

After Mr. Trump was charged again in Washington, accused of plotting to overturn the 2020 election, he settled on a legal team that included Mr. Blanche, who was already representing him in the Manhattan case where he faced charges of falsifying business records to cover up a sex scandal.

As each of the proceedings ground toward trial, Mr. Bove and Mr. Sauer joined the team.

Unlike Mr. Gaetz, all of the other Justice Department picks are courtroom veterans and, should they be confirmed, would bring to their jobs a wealth of experience in handling legal matters.

After attending Brooklyn Law School at night, Mr. Blanche spent several years as a prosecutor in the U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan, one of the country’s premier federal law enforcement agencies, eventually becoming a supervisor overseeing violent criminal cases. He then entered private practice and has represented people close to Mr. Trump, including Paul Manafort, the chairman of his 2016 presidential campaign, as well as Mr. Epshteyn.

Mr. Bove overlapped with Mr. Blanche in the prosecutor’s office, where he developed an expertise in classified information law and a reputation for handling complex international investigations. Among his most prominent cases was the prosecution of a South African crime lord, Paul Le Roux, and several mercenaries who worked for him, including a former U.S. soldier nicknamed Rambo.

Mr. Sauer, who once clerked for Justice Antonin Scalia, argued several appellate matters on Mr. Trump’s behalf. He challenged a gag order placed on Mr. Trump in his federal election case in Washington and appeared before the Supreme Court, ultimately winning a historic case that granted former presidents a broad form of immunity from criminal prosecution.

In private conversations, some of Mr. Trump’s lawyers have appeared not to be engaging in spin so much as displaying a sincere sense of outrage over the indictments against Mr. Trump, which they genuinely view as flawed at best and tainted by politics against their client at worst.

Still, in the course of defending Mr. Trump, each of the men has strayed at times beyond the strict boundaries of their roles as legal advocates, often advancing in court (or court filings) what amounted to their client’s political talking points.

Over and over, they amplified Mr. Trump’s claims that the cases brought against him by the special counsel Jack Smith, or by local prosecutors, were partisan witch hunts intended to destroy his chances of regaining power.

Just last month, for instance, Mr. Blanche and Mr. Bove put their names to a motion complaining that a sprawling government document detailing Mr. Trump’s attempts to reverse the last election was “a politically motivated manifesto” that prosecutors were seeking to release to the public “in the final weeks of the 2024 presidential election.”

In reality, the document was produced by Mr. Smith’s deputies on the Supreme Court’s orders as part of its immunity decision. And the judge overseeing the election case, Tanya S. Chutkan, scolded Mr. Blanche, Mr. Bove and other members of the team for “focusing on political rhetoric rather than addressing the legal issues at hand.”

“Not only is that focus unresponsive and unhelpful to the court,” Judge Chutkan wrote, “but it is also unbefitting of experienced defense counsel and undermining of the judicial proceedings in this case.”

In April, Mr. Sauer stepped out onto his own legal limb for Mr. Trump when he appeared in front of the Supreme Court to make his immunity claims for Mr. Trump.

In a now-famous exchange, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Mr. Sauer whether a president’s decision to use the military to assassinate a rival should be considered an official act “for which he could get immunity.”

“It would depend on the hypothetical,” Mr. Sauer said, shocking many legal experts. “We can see that could well be an official act.”

Beyond such acts of legal loyalty, Mr. Trump’s lawyers have also seemed to recognize the importance of proximity to this particular client.

Even before the trial in Manhattan, where Mr. Trump was convicted of 34 felonies, Mr. Blanche, who was based in New York City, bought a home in Palm Beach County, Fla., near Mar-a-Lago, his client’s private club and residence. At the trial, he displayed a close relationship with Mr. Trump, sitting inches from him during long days of testimony and standing, mute, by his side each time he addressed reporters.

This summer, some of Mr. Trump’s lawyers were seen in suites at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee.

Daniel C. Richman, a former federal prosecutor and law professor at Columbia University, said that Mr. Blanche, Mr. Bove and Mr. Sauer could face significant conflicts of interest once they enter office.

As Mr. Trump’s personal lawyers, he said, they still have a duty to protect his interests in the cases they worked on, and that could present a problem if their responsibilities to the public pull them in a different direction.

“We can’t be sure how this will play out,” Mr. Richman said, “but it’s certainly an issue to spot.”

Questions like these already seemed to have concerned top Democrats, including Senator Richard J. Durbin of Illinois, who will lead the party’s interrogation of the nominees at upcoming confirmation hearings.

“Donald Trump viewed the Justice Department as his personal law firm during his first term,” Mr. Durbin said on Friday, “and these selections — his personal attorneys — are poised to do his bidding.”

Mr. Burgum will be “chairman of the newly formed, and very important, National Energy Council,” Mr. Trump wrote in a statement, “which will consist of all departments and agencies involved in the permitting, production, generation, distribution, regulation, transportation, of ALL forms of American energy.”

“This council will oversee the path to U.S. ENERGY DOMINANCE by cutting red tape, enhancing private sector investments across all sectors of the Economy, and by focusing on INNOVATION over longstanding, but totally unnecessary, regulation,” he wrote.

Mr. Burgum will also have a seat on the National Security Council, Mr. Trump wrote, given the significant role of energy in foreign policy.

The position was inspired by President Barack Obama and President Biden, Democrats who created White House “climate czars,” said people close to Mr. Trump’s transition team, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the matter publicly.

Those climate advisers drove a “whole-of-government” approach to ensure that all federal agencies advanced efforts to reduce the nation’s use of planet-warming coal, oil and gas and to accelerate the use of wind and solar power and electric vehicles.

Mr. Trump’s energy czar is expected to have similar authorities — but effectively the opposite mandate.

“The White House should have someone who oversees energy policy because it cuts across almost all federal agencies,” said Thomas J. Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, a conservative research group focused on energy that helped shape Mr. Trump’s first-term energy agenda. “Obama and Biden set a lot of precedents. It’s an effective model.”

John Podesta, the current White House climate czar, who also briefly served in that role in the Obama administration, chuckled dryly at the compliment.

He said that if Mr. Burgum truly wanted to ensure supplies of affordable electricity, he would seek to retain the Biden administration’s signature climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act. The 2022 law pumps more than $370 billion into tax incentives for wind and solar power and electric vehicles.

“The support that we have given on the manufacturing and deployment side has resulted in a boom of clean, affordable electricity generation,” he said.

Mr. Trump’s transition team is already strategizing with Republicans on Capitol Hill about how to undo portions of that law.

The energy czar’s policy directive is reminiscent of the White House Energy Task Force overseen by Vice President Dick Cheney during the George W. Bush administration, aimed at ensuring that fossil fuels would remain the nation’s primary energy for “years down the road” and that the federal government would focus on increasing the supply of fossil fuels, rather than limiting demand.

Scientists have said that the United States and other major economies must stop developing new oil and gas projects to avert the most catastrophic effects of global warming. The burning of oil, gas and coal is the main driver of climate change.

The current year is shaping up to be the hottest in recorded history, and researchers say the world is on track for dangerous levels of warming this century.

Mr. Trump has long contended that using government levers to boost extraction and consumption would lower the cost of gasoline and electricity and ripple through the economy to bring down the cost of transportation, housing, food and other commodities.

Most economists say that energy prices are determined by global markets, rather than the actions of the U.S. government.

And it’s questionable how much more oil and gas companies would produce under different policies. The United States is already producing more oil than any other country in history, despite the Biden administration’s climate efforts.

Oil producers are also wary of a glut on the market, which could lower prices and profits.

“I’m less bullish on this than they are,” Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who directed the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office and now runs the American Action Forum, a conservative research organization, of the impact of an energy czar position. “I don’t think we’re going to notice a dramatic impact very quickly.”

Mr. Pyle noted another feature of the White House czar position that is likely to appeal to Mr. Trump: While the work and correspondence of officials in federal agencies are subject to government transparency laws, including Freedom of Information Act requests, the work of White House czars has more legal shields from those requirements.

“There is an advantage that they don’t have to be as transparent,” he said.

A correction was made on

Nov. 15, 2024

:

An earlier version of this article misstated the name of council on which Mr. Burgum would sit. It is the National Security Council, not the White House Security Council.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at nytnews@nytimes.com.Learn more

Since Mr. Trump won the Nov. 5 election, many Iranian former officials, pundits and media outlets have been publicly advocating for Tehran to try to engage with the president-elect and pursue a more conciliatory approach, despite vows from Mr. Trump’s allies to renew a high-pressure campaign against Iran.

U.S. officials have said that Iran sought to kill Mr. Trump in revenge for ordering the 2020 drone strike that killed Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, the commander who directed Iran’s militias and proxy forces. The Department of Justice has issued two indictments that officials said were related to Iranian plotting against Mr. Trump.

American officials have also accused Iran of plotting to assassinate other Trump administration figures.

The officials interviewed for this story spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive diplomatic messages.

The message exchange was first reported by The Wall Street Journal.

The message from Iran repeated Tehran’s contention that the killing of General Suleimani was a criminal act, the two U.S. officials said. But it also said that Iran did not want to kill Mr. Trump, according to the U.S. officials, an Iranian official and an Iranian analyst who talks with both sides.

The Iranians said the message to the United States indicated that Iran sought to avenge the killing of General Suleimani through international legal means.

The U.S. officials said the Iranian message was not a letter from a specific official. But the Iranian official and analyst said it was from Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Iran’s mission to the United Nations declined to comment on the message exchange. But it said in a statement that Iran was committed to responding to General Suleimani’s killing “through legal and judicial avenues.”

During the presidential campaign, American officials warned that Iran was plotting to kill Mr. Trump.

Federal prosecutors in Manhattan said last week that Iranian plotters had discussed a plan to assassinate him, which Iran’s Foreign Ministry called baseless.

In July, Asif Raza Merchant, a Pakistani man who had visited Iran, was arrested in New York and was later charged with trying to hire a hit man to assassinate American politicians. Investigators believe his potential targets included Mr. Trump.

Intelligence about Iran’s intentions was provided to the Secret Service, which added counter-sniper teams to Mr. Trump’s protective detail ahead of the assassination attempt on him in July, in Butler, Pa., by a lone gunman with no ties to Tehran, according to U.S. officials.

Iran had considered Mr. Trump to be a difficult target because of his Secret Service protection. But after the attempted assassination in Pennsylvania and another near Mr. Trump’s golf course in Florida, U.S. intelligence agencies assessed that Iran grew more confident that the former president could be successfully targeted.

That assessment of a growing threat, combined with the attempts on Mr. Trump’s life, prompted both an intense security review and a diplomatic campaign to convince Iran that it was making a grave miscalculation, according to officials.

Elon Musk, who has become a close ally of Mr. Trump, met with Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations on Monday, at Mr. Musk’s request, the Iranians said — a sign that it is not only the lame duck Democratic administration that is looking to avoid a direct clash, but also the Trump camp. The Iranians said the meeting with Ambassador Amir Saied Iravani, at a secret location in New York City, was about defusing tensions between Iran and the United States under the Trump administration.

Mr. Musk did not respond to a request for comment.

The United States and Iran have not had official diplomatic relations since Iran’s 1979 revolution, when 52 Americans were taken hostage in the U.S. embassy in Tehran, and held for more than a year.

The Swiss embassy in Tehran is the official diplomatic liaison between the two nations, but American and Iranian officials have held direct and indirect negotiations in recent years on a host of issues, including Iran’s nuclear program, regional tensions and swapping detainees.

The U.S. and Iranian messages were sent through the Swiss, according to the Iranian official and the analyst.

It can be downright confusing. Here’s what to expect:

JD Vance: vice president

How Vance’s Senate seat in Ohio will be filled

When Mr. Trump named Ohio’s junior senator as his running mate, he did so knowing that the state’s Republican governor, Mike DeWine, would get to appoint Mr. Vance’s temporary replacement if the pair was elected.

Ohio is one of 45 states that grant that power to the governor. That means Republicans, who flipped control of the Senate in the Nov. 5 election, will almost certainly keep the seat until at least 2026, when there will be a special election to determine who serves out the remaining two years of Mr. Vance’s term.

The next regular election for the seat will be in 2028. The state has turned increasingly red, and its Democratic senator, Sherrod Brown, lost re-election in November.

Marco Rubio: Secretary of State

How Rubio’s Senate seat in Florida will be filled

Should the Senate confirm Florida’s senior senator for the prestigious cabinet role, the state’s governor, Ron DeSantis, would choose his replacement.

Mr. DeSantis, who endorsed Mr. Trump after dropping his own Republican presidential bid, would appoint someone to the seat, and then a special election would be held in 2026 to fill the remaining two years of Mr. Rubio’s term. The seat would be up for election again in 2028. Florida has not elected a Democratic senator in over a decade.

Matt Gaetz: Attorney General

How Gaetz’s House seat in Florida will be filled

Mr. Gaetz, selected for attorney general, has been one of Mr. Trump’s most polarizing cabinet picks. A hard-right provocateur, Mr. Gaetz cruised to a fifth term in his safely Republican House district on Florida’s panhandle this month. Vacancies in the House — where Republicans kept a slim majority in the election — are filled differently than those in the Senate.

A Florida state law says that the governor, in consultation with Florida’s secretary of state, must select the dates of a special primary election and a special election.

Mr. DeSantis said he instructed Cord Byrd, the secretary of state and a Republican, to schedule a special election immediately to fill the seat, and Mr. Byrd said he would do so soon. But a date has not yet been announced.

Mr. DeSantis’s urgency to fill the vacancy contrasted sharply with the timing of a special election after the death of Representative Alcee Hastings, a Democrat, in April 2021. Mr. DeSantis scheduled special primaries seven months later, and a special general election was held in January 2022.

Mike Waltz: National Security Adviser

How Waltz’s House seat in Florida will be filled

The former Green Beret, who received four Bronze Stars and is known for his hawkish views on national security, was re-elected with more than 65 percent of the vote in November in east-central Florida. His district, Florida’s Sixth, is one of the most Republican-leaning areas in the country.

The seat will be filled in a special election, which Mr. DeSantis has also said that he wants scheduled immediately. No date has yet been announced.

Elise Stefanik: United Nations Ambassador

How Stefanik’s House seat in New York will be filled

The No. 4 leader of the House Republicans was rewarded for her unflagging loyalty to Mr. Trump, who offered her the role of U.N. ambassador. She will leave what is viewed as a safe G.O.P. district in upstate New York.

Under state law, Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York, a Democrat, will have 10 days after Ms. Stefanik resigns to call for a special election, which must take place between 70 and 80 days after that.

Ms. Stefanik has not yet resigned; it is customary for nominees to wait until after Senate confirmation before they do. That process will begin after Mr. Trump takes office.

Kristi Noem: Homeland Security Secretary

How Noem’s job as South Dakota governor will be filled

In filling all the vacancies that Mr. Trump’s nominees would create, the process of installing South Dakota’s next governor may be the simplest.

The office would be taken over by the lieutenant governor, Larry Rhoden, a Republican who has been Ms. Noem’s running mate for two election cycles.

At one point during the 2024 presidential election, Ms. Noem drew mention as a possible contender to be Mr. Trump’s running mate. Then the release of her memoir brought negative attention over her account of shooting her dog in a gravel pit and her false claims about having met with Kim Jong-un, the North Korean leader.

Her cabinet post requires Senate confirmation.

If there is a through line to Mr. Kennedy’s thinking, it appears to be a deep mistrust of corporate influence on health and medicine. In some cases, that has led him to support positions that are also embraced by public health professionals, including his push to get ultra-processed foods, which have been linked to obesity, off grocery store shelves. His disdain for profit-seeking pharmaceutical manufacturers and food companies drew applause on the campaign trail.

People close to him say his commitment to “make America healthy again” is heartfelt.

“This is his life’s mission,” said Brian Festa, a founder of We the Patriots U.S.A., a “medical freedom” group that has pushed back on vaccine mandates, who said he has known Mr. Kennedy for years.

But like Mr. Trump, Mr. Kennedy also has a tendency to float wild theories based on scanty evidence. And he has hinted at taking actions, like prosecuting leading medical journals, that have unnerved the medical community. On Friday, many leading public health experts reacted to his nomination with alarm.

“This is the first time we’ve ever had someone that walking in the door whose public views, you just can’t trust,” said Dr. Georges Benjamin, the executive director of the American Public Health Association, which represents 25,000 public health professionals.

He called Mr. Kennedy, an environmental lawyer, “totally unprepared, by skill and by training,” for the job of secretary, which involves managing a department with more than 80,000 employees and 13 operating divisions, overseeing everything from Medicare to biomedical research.

Mike Pence, the former vice president under Mr. Trump, publicly opposed Mr. Kennedy’s nomination on Friday, citing his support for abortion rights.

The pharmaceutical industry’s trade group issued a statement neither praising nor criticizing Mr. Kennedy’s nomination. Calling itself “a crown jewel of the American economy,” the group vowed to “work with the Trump administration to further strengthen our innovation ecosystem and improve health care for patients.” Shares of stock in vaccine makers fell after Mr. Trump announced his selection of Mr. Kennedy on Thursday.

Mr. Kennedy did not respond to a request for an interview, and he has not publicly outlined his priorities. But if he is confirmed by the Senate, he would have wide latitude as health secretary, and has forecast his plans to shake things up.

In an interview in January 2024 with Dr. Mark Hyman, before he suspended his own independent presidential campaign and endorsed Mr. Trump, he spoke about what he would do if elected, outlining some of his lesser-known goals.

He said he would steer the nearly $48 billion annual budget of the National Institutes of Health away from drug development and toward studies that would explain high rates of chronic disease. He also said he would seek to prosecute medical journals like The Lancet and The New England Journal of Medicine under the federal anti-corruption statute.

“I’m going to litigate against you under the racketeering laws, under the general tort laws,” he said during the interview. “I’m going to find a way to sue you unless you come up with a plan right now to show how you’re going to start publishing real science and stop retracting the real science and publishing the fake pharmaceutical science by these phony industry mercenaries, scientists.”

More recently, Mr. Kennedy has said Mr. Trump would advise communities to stop fluoridating their water, contradicting the advice of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which cites fluoridation to reduce tooth decay as on of the ten great public health achievements of the 20th century. He has said he would slash 600 jobs at the N.I.H. and has instructed Food and Drug Administration officials to “preserve your records” and “pack your bags.”

Mr. Kennedy has argued that the F.D.A. is a victim of “corporate capture.” Under a three-decade-old “user fee” program, drug, device and biotech companies make payments to the agency partly to seek product approvals. The fees now account for nearly half the F.D.A.’s budget.

“The F.D.A. is just a sock puppet to the industries it is supposed to regulate,” Mr. Kennedy said in the interview with Dr. Hyman. “All of this is easily changed. I’m not saying I’m going to be able to accomplish it all on Day 1, but I’m going to accomplish it very quickly.”

Public health experts typically focus on Mr. Kennedy’s views on vaccination. Mr. Kennedy has cast doubt on Covid vaccines and has promoted the long-debunked theory that vaccines cause autism. His detractors say that his critiques of vaccine safety have cost lives, pointing in particular to a visit Mr. Kennedy made to Samoa in 2019.

That year, the island nation put its measles vaccination program on hold after the death of two infants who had received measles shots. Mr. Kennedy visited and, according to news reports, met with a prominent vaccine opponent, giving a boost to the anti-vaccination movement there.

The deaths were subsequently attributed to a mistake by the nurses who administered the vaccine, not to the vaccine itself. But the dip in vaccination rates led to a measles outbreak and 83 deaths.

Dr. Jonathan E. Howard, an associate professor of neurology and psychiatry at New York University who has been tracking the anti-vaccine movement for the past 15 years, said Mr. Kennedy would be “a disaster” as health secretary, adding, “He is an anti-vaccine paranoid crank who has a trail of dead children in Samoa.”

Often, Mr. Kennedy uses a “we don’t know” construction to spin out unproven theories, such as his suggestion that the coronavirus might have been engineered to attack specific races.

“Covid-19 is targeted to attack Caucasians and Black people,” Mr. Kennedy said at a fund-raiser, according to The New York Post. “The people who are most immune are Ashkenazi Jews and Chinese.”

“We don’t know whether it was deliberately targeted or not, but there are papers out there that show the racial or ethnic differential and impact,” he added.

Mr. Kennedy was apparently referring to a 2020 study looking at genetic differences in Covid-19 patients, but numerous studies examining racial disparities attribute them to socioeconomic factors, including poverty and lack of access to health care.

Mr. Kennedy also has repeatedly suggested that chemicals in the water might be responsible for “sexual dysphoria” in children. In a clip aired by CNN, he noted that atrazine, a herbicide sometimes found in well water in agricultural areas, will “concentrate and forcibly feminize” frogs. He went on, “What this does to sexual development in children, nobody knows.”

There is no evidence that the chemical, typically used on farms to kill weeds, causes the same effects in children, although studies show it has been linked to birth defects in babies whose mothers are exposed to it. But according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, an arm of the C.D.C., “Most people are not exposed to atrazine on a regular basis.”

Mr. Kennedy came to health advocacy through his work as an environmental lawyer. In 1999, he was named a hero of the planet by Time magazine for his work with the Riverkeeper organization, among the groups credited with cleaning up New York’s polluted Hudson River. One of his aims was to get mercury out of waterways.

In a speech last year at Hillsdale College, he said that in 2005, when he was giving speeches around the country, mothers of children with autism approached him to ask him to take a look at vaccines, some of which had in the past contained a mercury-based preservative, thimerosal. The preservative was removed by manufacturers in 2001 at the request of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and subsequent studies showed no link between the preservative and autism.

In the years since, Mr. Kennedy has made millions of dollars railing against vaccines. The windfall has come through books, including one denigrating Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the former government scientist both celebrated and despised for his work on Covid, and through Children’s Health Defense, the nonprofit he has used as a platform to sow doubts about vaccination.

Allies of Mr. Kennedy say he has earned the right to make policy, given the support he generated while campaigning alongside Mr. Trump. Calley Means, a health care entrepreneur who has been an adviser to Mr. Kennedy and who was instrumental in connecting him to Mr. Trump, said in an interview last week that Mr. Kennedy had “a true mandate to take on broken health care institutions, and to deliver the change.”

Now, after fighting for Mr. Trump in case after case that they helped turn into a form of political theater, some of those lawyers are being rewarded again for their work. Mr. Trump has said he intends to nominate them to high-ranking posts in the Justice Department, which he has made clear he wants to operate as a legal arm of the White House rather than with the quasi-independence that has been the post-Watergate norm.

After the president-elect’s announcement this week that he wants Matt Gaetz, the controversial former Florida congressman and a longtime ally, to be his attorney general, he named Todd Blanche and Emil Bove, two experienced former federal prosecutors who took the lead in defending Mr. Trump at his state trial in Manhattan and against two federal indictments, to fill the No. 2 and No. 3 positions in the department.

A third lawyer, D. John Sauer, who was the Missouri solicitor general and oversaw Mr. Trump’s appellate battles, was chosen to represent the department in front of the Supreme Court as the U.S. solicitor general.

Another lawyer, Stanley Woodward Jr., who defended several people in Mr. Trump’s orbit and helped in the process of vetting his vice-presidential pick, has also been mentioned for a top legal job, though it remains unclear if he will actually receive a role.

Throughout American history, presidents have made a habit of installing lawyers close to them in powerful positions. George Washington picked his personal lawyer, Edmund Randolph, as his first attorney general, and John F. Kennedy put his brother Robert in the post.

But until now, no president had ever nominated his own criminal defense team to top jobs in the Justice Department. And Mr. Trump’s choice of Mr. Blanche, Mr. Bove and Mr. Sauer runs the risk of turning the agency into something it was never meant to be: the president’s private law firm.

“It’s a strange move, for sure, although that’s not to say that you can’t be Trump’s defense lawyer and still be a good lawyer,” said Alan Rozenshtein, a former Justice Department official who teaches at the University of Minnesota Law School. “Still, it raises all sorts of complex conflicts of interest and raises questions about whether the Justice Department should exist to protect the president of the United States.”

At the same time, there has never been a president who entered office having experienced a criminal trial, and three other indictments in different places.

Mr. Trump’s transition office did not respond to an email seeking comment.

When Mr. Trump first came under investigation after he left office, he had a hard time finding — and keeping — lawyers to defend him.

Two of his original lawyers, James Trusty and John Rowley, stepped down from the job shortly after he was indicted in Florida in June 2023 on charges of mishandling classified documents. The month before the indictment was issued, another lawyer, Timothy Parlatore, also quit the team, citing problems with Mr. Trump’s adviser Boris Epshteyn.

After Mr. Trump was charged again in Washington, accused of plotting to overturn the 2020 election, he settled on a legal team that included Mr. Blanche, who was already representing him in the Manhattan case where he faced charges of falsifying business records to cover up a sex scandal.

As each of the proceedings ground toward trial, Mr. Bove and Mr. Sauer joined the team.

Unlike Mr. Gaetz, all of the other Justice Department picks are courtroom veterans and, should they be confirmed, would bring to their jobs a wealth of experience in handling legal matters.

After attending Brooklyn Law School at night, Mr. Blanche spent several years as a prosecutor in the U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan, one of the country’s premier federal law enforcement agencies, eventually becoming a supervisor overseeing violent criminal cases. He then entered private practice and has represented people close to Mr. Trump, including Paul Manafort, the chairman of his 2016 presidential campaign, as well as Mr. Epshteyn.

Mr. Bove overlapped with Mr. Blanche in the prosecutor’s office, where he developed an expertise in classified information law and a reputation for handling complex international investigations. Among his most prominent cases was the prosecution of a South African crime lord, Paul Le Roux, and several mercenaries who worked for him, including a former U.S. soldier nicknamed Rambo.

Mr. Sauer, who once clerked for Justice Antonin Scalia, argued several appellate matters on Mr. Trump’s behalf. He challenged a gag order placed on Mr. Trump in his federal election case in Washington and appeared before the Supreme Court, ultimately winning a historic case that granted former presidents a broad form of immunity from criminal prosecution.

In private conversations, some of Mr. Trump’s lawyers have appeared not to be engaging in spin so much as displaying a sincere sense of outrage over the indictments against Mr. Trump, which they genuinely view as flawed at best and tainted by politics against their client at worst.

Still, in the course of defending Mr. Trump, each of the men has strayed at times beyond the strict boundaries of their roles as legal advocates, often advancing in court (or court filings) what amounted to their client’s political talking points.

Over and over, they amplified Mr. Trump’s claims that the cases brought against him by the special counsel Jack Smith, or by local prosecutors, were partisan witch hunts intended to destroy his chances of regaining power.

Just last month, for instance, Mr. Blanche and Mr. Bove put their names to a motion complaining that a sprawling government document detailing Mr. Trump’s attempts to reverse the last election was “a politically motivated manifesto” that prosecutors were seeking to release to the public “in the final weeks of the 2024 presidential election.”

In reality, the document was produced by Mr. Smith’s deputies on the Supreme Court’s orders as part of its immunity decision. And the judge overseeing the election case, Tanya S. Chutkan, scolded Mr. Blanche, Mr. Bove and other members of the team for “focusing on political rhetoric rather than addressing the legal issues at hand.”

“Not only is that focus unresponsive and unhelpful to the court,” Judge Chutkan wrote, “but it is also unbefitting of experienced defense counsel and undermining of the judicial proceedings in this case.”

In April, Mr. Sauer stepped out onto his own legal limb for Mr. Trump when he appeared in front of the Supreme Court to make his immunity claims for Mr. Trump.

In a now-famous exchange, Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked Mr. Sauer whether a president’s decision to use the military to assassinate a rival should be considered an official act “for which he could get immunity.”

“It would depend on the hypothetical,” Mr. Sauer said, shocking many legal experts. “We can see that could well be an official act.”

Beyond such acts of legal loyalty, Mr. Trump’s lawyers have also seemed to recognize the importance of proximity to this particular client.

Even before the trial in Manhattan, where Mr. Trump was convicted of 34 felonies, Mr. Blanche, who was based in New York City, bought a home in Palm Beach County, Fla., near Mar-a-Lago, his client’s private club and residence. At the trial, he displayed a close relationship with Mr. Trump, sitting inches from him during long days of testimony and standing, mute, by his side each time he addressed reporters.

This summer, some of Mr. Trump’s lawyers were seen in suites at the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee.

Daniel C. Richman, a former federal prosecutor and law professor at Columbia University, said that Mr. Blanche, Mr. Bove and Mr. Sauer could face significant conflicts of interest once they enter office.

As Mr. Trump’s personal lawyers, he said, they still have a duty to protect his interests in the cases they worked on, and that could present a problem if their responsibilities to the public pull them in a different direction.

“We can’t be sure how this will play out,” Mr. Richman said, “but it’s certainly an issue to spot.”

Questions like these already seemed to have concerned top Democrats, including Senator Richard J. Durbin of Illinois, who will lead the party’s interrogation of the nominees at upcoming confirmation hearings.

“Donald Trump viewed the Justice Department as his personal law firm during his first term,” Mr. Durbin said on Friday, “and these selections — his personal attorneys — are poised to do his bidding.”

Mr. Burgum will be “chairman of the newly formed, and very important, National Energy Council,” Mr. Trump wrote in a statement, “which will consist of all departments and agencies involved in the permitting, production, generation, distribution, regulation, transportation, of ALL forms of American energy.”

“This council will oversee the path to U.S. ENERGY DOMINANCE by cutting red tape, enhancing private sector investments across all sectors of the Economy, and by focusing on INNOVATION over longstanding, but totally unnecessary, regulation,” he wrote.

Mr. Burgum will also have a seat on the National Security Council, Mr. Trump wrote, given the significant role of energy in foreign policy.

The position was inspired by President Barack Obama and President Biden, Democrats who created White House “climate czars,” said people close to Mr. Trump’s transition team, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss the matter publicly.

Those climate advisers drove a “whole-of-government” approach to ensure that all federal agencies advanced efforts to reduce the nation’s use of planet-warming coal, oil and gas and to accelerate the use of wind and solar power and electric vehicles.

Mr. Trump’s energy czar is expected to have similar authorities — but effectively the opposite mandate.

“The White House should have someone who oversees energy policy because it cuts across almost all federal agencies,” said Thomas J. Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, a conservative research group focused on energy that helped shape Mr. Trump’s first-term energy agenda. “Obama and Biden set a lot of precedents. It’s an effective model.”

John Podesta, the current White House climate czar, who also briefly served in that role in the Obama administration, chuckled dryly at the compliment.

He said that if Mr. Burgum truly wanted to ensure supplies of affordable electricity, he would seek to retain the Biden administration’s signature climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act. The 2022 law pumps more than $370 billion into tax incentives for wind and solar power and electric vehicles.

“The support that we have given on the manufacturing and deployment side has resulted in a boom of clean, affordable electricity generation,” he said.

Mr. Trump’s transition team is already strategizing with Republicans on Capitol Hill about how to undo portions of that law.

The energy czar’s policy directive is reminiscent of the White House Energy Task Force overseen by Vice President Dick Cheney during the George W. Bush administration, aimed at ensuring that fossil fuels would remain the nation’s primary energy for “years down the road” and that the federal government would focus on increasing the supply of fossil fuels, rather than limiting demand.

Scientists have said that the United States and other major economies must stop developing new oil and gas projects to avert the most catastrophic effects of global warming. The burning of oil, gas and coal is the main driver of climate change.

The current year is shaping up to be the hottest in recorded history, and researchers say the world is on track for dangerous levels of warming this century.

Mr. Trump has long contended that using government levers to boost extraction and consumption would lower the cost of gasoline and electricity and ripple through the economy to bring down the cost of transportation, housing, food and other commodities.

Most economists say that energy prices are determined by global markets, rather than the actions of the U.S. government.

And it’s questionable how much more oil and gas companies would produce under different policies. The United States is already producing more oil than any other country in history, despite the Biden administration’s climate efforts.

Oil producers are also wary of a glut on the market, which could lower prices and profits.

“I’m less bullish on this than they are,” Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who directed the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office and now runs the American Action Forum, a conservative research organization, of the impact of an energy czar position. “I don’t think we’re going to notice a dramatic impact very quickly.”

Mr. Pyle noted another feature of the White House czar position that is likely to appeal to Mr. Trump: While the work and correspondence of officials in federal agencies are subject to government transparency laws, including Freedom of Information Act requests, the work of White House czars has more legal shields from those requirements.

“There is an advantage that they don’t have to be as transparent,” he said.

A correction was made on

Nov. 15, 2024

:

An earlier version of this article misstated the name of council on which Mr. Burgum would sit. It is the National Security Council, not the White House Security Council.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at nytnews@nytimes.com.Learn more

Since Mr. Trump won the Nov. 5 election, many Iranian former officials, pundits and media outlets have been publicly advocating for Tehran to try to engage with the president-elect and pursue a more conciliatory approach, despite vows from Mr. Trump’s allies to renew a high-pressure campaign against Iran.

U.S. officials have said that Iran sought to kill Mr. Trump in revenge for ordering the 2020 drone strike that killed Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, the commander who directed Iran’s militias and proxy forces. The Department of Justice has issued two indictments that officials said were related to Iranian plotting against Mr. Trump.

American officials have also accused Iran of plotting to assassinate other Trump administration figures.

The officials interviewed for this story spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive diplomatic messages.

The message exchange was first reported by The Wall Street Journal.

The message from Iran repeated Tehran’s contention that the killing of General Suleimani was a criminal act, the two U.S. officials said. But it also said that Iran did not want to kill Mr. Trump, according to the U.S. officials, an Iranian official and an Iranian analyst who talks with both sides.

The Iranians said the message to the United States indicated that Iran sought to avenge the killing of General Suleimani through international legal means.

The U.S. officials said the Iranian message was not a letter from a specific official. But the Iranian official and analyst said it was from Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Iran’s mission to the United Nations declined to comment on the message exchange. But it said in a statement that Iran was committed to responding to General Suleimani’s killing “through legal and judicial avenues.”

During the presidential campaign, American officials warned that Iran was plotting to kill Mr. Trump.

Federal prosecutors in Manhattan said last week that Iranian plotters had discussed a plan to assassinate him, which Iran’s Foreign Ministry called baseless.

In July, Asif Raza Merchant, a Pakistani man who had visited Iran, was arrested in New York and was later charged with trying to hire a hit man to assassinate American politicians. Investigators believe his potential targets included Mr. Trump.

Intelligence about Iran’s intentions was provided to the Secret Service, which added counter-sniper teams to Mr. Trump’s protective detail ahead of the assassination attempt on him in July, in Butler, Pa., by a lone gunman with no ties to Tehran, according to U.S. officials.

Iran had considered Mr. Trump to be a difficult target because of his Secret Service protection. But after the attempted assassination in Pennsylvania and another near Mr. Trump’s golf course in Florida, U.S. intelligence agencies assessed that Iran grew more confident that the former president could be successfully targeted.

That assessment of a growing threat, combined with the attempts on Mr. Trump’s life, prompted both an intense security review and a diplomatic campaign to convince Iran that it was making a grave miscalculation, according to officials.

Elon Musk, who has become a close ally of Mr. Trump, met with Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations on Monday, at Mr. Musk’s request, the Iranians said — a sign that it is not only the lame duck Democratic administration that is looking to avoid a direct clash, but also the Trump camp. The Iranians said the meeting with Ambassador Amir Saied Iravani, at a secret location in New York City, was about defusing tensions between Iran and the United States under the Trump administration.

Mr. Musk did not respond to a request for comment.

The United States and Iran have not had official diplomatic relations since Iran’s 1979 revolution, when 52 Americans were taken hostage in the U.S. embassy in Tehran, and held for more than a year.

The Swiss embassy in Tehran is the official diplomatic liaison between the two nations, but American and Iranian officials have held direct and indirect negotiations in recent years on a host of issues, including Iran’s nuclear program, regional tensions and swapping detainees.

The U.S. and Iranian messages were sent through the Swiss, according to the Iranian official and the analyst.

It can be downright confusing. Here’s what to expect:

JD Vance: vice president

How Vance’s Senate seat in Ohio will be filled

When Mr. Trump named Ohio’s junior senator as his running mate, he did so knowing that the state’s Republican governor, Mike DeWine, would get to appoint Mr. Vance’s temporary replacement if the pair was elected.

Ohio is one of 45 states that grant that power to the governor. That means Republicans, who flipped control of the Senate in the Nov. 5 election, will almost certainly keep the seat until at least 2026, when there will be a special election to determine who serves out the remaining two years of Mr. Vance’s term.

The next regular election for the seat will be in 2028. The state has turned increasingly red, and its Democratic senator, Sherrod Brown, lost re-election in November.

Marco Rubio: Secretary of State

How Rubio’s Senate seat in Florida will be filled

Should the Senate confirm Florida’s senior senator for the prestigious cabinet role, the state’s governor, Ron DeSantis, would choose his replacement.

Mr. DeSantis, who endorsed Mr. Trump after dropping his own Republican presidential bid, would appoint someone to the seat, and then a special election would be held in 2026 to fill the remaining two years of Mr. Rubio’s term. The seat would be up for election again in 2028. Florida has not elected a Democratic senator in over a decade.

Matt Gaetz: Attorney General

How Gaetz’s House seat in Florida will be filled

Mr. Gaetz, selected for attorney general, has been one of Mr. Trump’s most polarizing cabinet picks. A hard-right provocateur, Mr. Gaetz cruised to a fifth term in his safely Republican House district on Florida’s panhandle this month. Vacancies in the House — where Republicans kept a slim majority in the election — are filled differently than those in the Senate.

A Florida state law says that the governor, in consultation with Florida’s secretary of state, must select the dates of a special primary election and a special election.

Mr. DeSantis said he instructed Cord Byrd, the secretary of state and a Republican, to schedule a special election immediately to fill the seat, and Mr. Byrd said he would do so soon. But a date has not yet been announced.

Mr. DeSantis’s urgency to fill the vacancy contrasted sharply with the timing of a special election after the death of Representative Alcee Hastings, a Democrat, in April 2021. Mr. DeSantis scheduled special primaries seven months later, and a special general election was held in January 2022.

Mike Waltz: National Security Adviser

How Waltz’s House seat in Florida will be filled

The former Green Beret, who received four Bronze Stars and is known for his hawkish views on national security, was re-elected with more than 65 percent of the vote in November in east-central Florida. His district, Florida’s Sixth, is one of the most Republican-leaning areas in the country.

The seat will be filled in a special election, which Mr. DeSantis has also said that he wants scheduled immediately. No date has yet been announced.

Elise Stefanik: United Nations Ambassador

How Stefanik’s House seat in New York will be filled

The No. 4 leader of the House Republicans was rewarded for her unflagging loyalty to Mr. Trump, who offered her the role of U.N. ambassador. She will leave what is viewed as a safe G.O.P. district in upstate New York.

Under state law, Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York, a Democrat, will have 10 days after Ms. Stefanik resigns to call for a special election, which must take place between 70 and 80 days after that.

Ms. Stefanik has not yet resigned; it is customary for nominees to wait until after Senate confirmation before they do. That process will begin after Mr. Trump takes office.

Kristi Noem: Homeland Security Secretary

How Noem’s job as South Dakota governor will be filled

In filling all the vacancies that Mr. Trump’s nominees would create, the process of installing South Dakota’s next governor may be the simplest.

The office would be taken over by the lieutenant governor, Larry Rhoden, a Republican who has been Ms. Noem’s running mate for two election cycles.

At one point during the 2024 presidential election, Ms. Noem drew mention as a possible contender to be Mr. Trump’s running mate. Then the release of her memoir brought negative attention over her account of shooting her dog in a gravel pit and her false claims about having met with Kim Jong-un, the North Korean leader.

Her cabinet post requires Senate confirmation.

Comments( 0 )

0 0 3

0 0 4

0 0 5

0 0 5