Latino men voted for Trump in large numbers. Here’s what they hope he delivers.

Posted on 12/01/2024

Latino men vaulted into the spotlight with their greater-than-expected support for President-elect Donald Trump. Soon, they’ll be looking for returns on their votes.

U.S. Hispanics, who are younger than the general population, are driving the growth of the labor force — by 2030, they will account for 1 out of every 5 workers. In interviews before and after the election, Latino men repeatedly said they want relief from the rising cost of living and more job and business opportunities.

While Hispanic men overall are doing better than Latinas and other groups in some quality-of-life measures, they lag behind white and other men in many areas.

“The [next] administration has a big, big task, especially because they have the House and Senate. President Trump can’t afford to not deliver on some of the things that the community really wants,” said Abraham Enriquez, founder and president of Bienvenido US, a conservative Latino advocacy group that helped turn out Hispanic voters for Trump and Republicans.

“What does it mean for a young Hispanic man that is of Mexican descent such as myself?” Enriquez, 29, said. “Homeownership is at the top of my priorities. It’s the one pathway to generational wealth.”

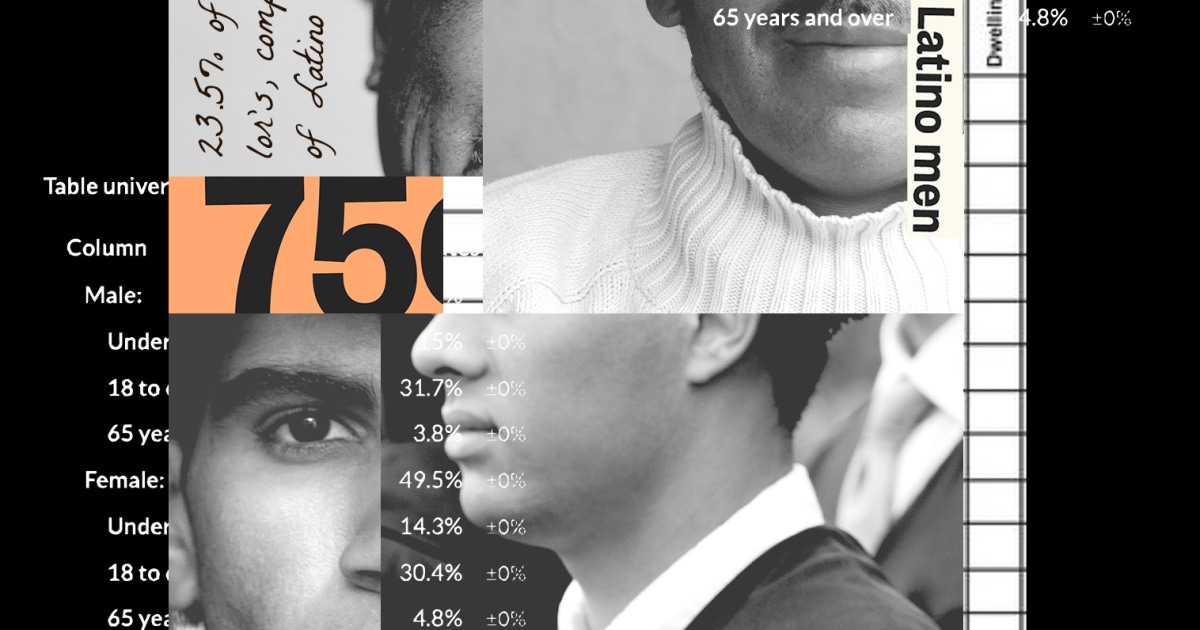

Close to 1 in 10 people in the U.S., about 32 million people, are Hispanic males; the U.S. Latino population is nearly evenly divided between men and women. Latino males are younger than men in the U.S. overall and have a higher participation in the workforce than any other racial group.

NBC News exit polls showed Trump won 55% support from Hispanic men, while a poll for Latino and other progressive groups reported he won 43%.

The story of Hispanic men is a two-part story, especially in the areas of education and income, according to Mark Hugo Lopez, director of race and ethnicity research at the Pew Research Center.

“Hispanic men have made progress, but so did other people too,” Lopez said. “Hispanic men face many pressures, pressures about family, about economics, about roles they are expected to play.”

Hispanic men have seen solid progress in educational attainment: The share of Latino men ages 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree grew at about the same rate as white men over the last two decades, according to Pew.

The college conundrum

Blanco, a hotel sales coordinator, is also a full-time student at Florida International University. He had not wanted to attend college, despite encouragement from his college-educated parents, who moved the family from Caracas in 2010. He hopes to build a career in sales.

“I told my dad before, if he wasn’t paying for it, I probably wouldn’t do it,” he said of attending college. “I don’t see the point of it in my specific industry — I’ve learned more on the jobs than what I learned in any college class.”

Living at home, he’s been able to save. His earnings at his hotel job have ended the days of getting tax refunds; now, he pays income taxes. He hopes Trump and the next Congress will approve tax breaks and cut spending so he can keep more of his money, he said.

Blanco’s initial lack of interest in college is not uncommon. Victor Saénz, an education professor at University of Texas at Austin, and Luis Ponjuán, an associate professor of education at Texas A&M, began focusing their research on Hispanic men 15 years ago, after noticing their college enrollment numbers were dropping while Latinas’ were growing.

Though the same share of Hispanic men and women 25 and older had bachelor’s degrees in 2003, Latinas have been outpacing men since then, though numbers for both have been improving.

“So many young men that we work with feel left behind, abandoned, not like they’re the focal point of our sort of government efforts, whether it’s public education or public policies,” he said.

Early in their research, there were signs that economics were driving the decisions of young men and boys on whether to attend college and what career pathways they were choosing, Saénz said.

“For so many young men, they decide not to go to college because it seems like it’s a waste of time, it’s an opportunity cost. [They] could be going to work and trying to contribute to their family. … Those are very strong drivers for so many young men, and that’s often rooted in their own notion of being a man, right?” Saénz said.

Some Hispanic men are defining college differently. Ponjuán told the story of a Corpus Christi man in his 40s who earned a commercial driver’s license certificate to get a better job and therefore considered himself a college graduate; he told Ponjuán he could now show his son the value of college education.

But Ponjuán warned that some jobs with high concentrations of Latinos become harder to do in middle age.

“Latino men are checking out because they are the labor force for a lot of these jobs that require manual labor and blue-collar workers,” Ponjuán said. “Young men enter these careers, and by the time they reach 34, 35, their bodies give out and they are no longer able to go into management, because they don’t have a degree or they don’t have the skill sets.”

The median age of Hispanic men is 30.6, while the median age for the general population is 38.1.

Hispanic men work in some of the most dangerous jobs, mostly in transportation and construction, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The most recent census of fatal occupational injuries issued by BLS showed Latino workers were 30% more likely to suffer a fatal injury on the job than other workers overall.

Jun Garza, 43, who was born and raised in San Antonio, is part owner of a small construction and remodeling business there. He didn’t finish high school and was on his own at 15. But he had skills in various trades he learned from his father and uncle, who often used him for jobs because “I was a hard worker.”

He recently injured himself falling off a ladder while trimming a tree at his home. A light bulb went off that “this is not something I’ll be able to do my whole life,” he said; the work has already taken a toll on his body. “I’m not super old, but I will be older, and when I’m too old, they may not want to hire me.”

Garza is now earning his GED and hopes to earn a construction manager certification through community college.

Like Garza, some Hispanic men are using their blue-collar skills to start their own contracting, landscaping, restaurant and other businesses.

“Latinos are starting small businesses out of necessity,” said Juan Proaño, an entrepreneur and the CEO of League of United Latin American Citizens, the nation’s oldest Latino advocacy group. “When they can’t find a job to support their families, they venture out to start one. The problem is they have to finance to grow that business to scale. While there are a lot of Latino startups, there are not a lot of scalable businesses, businesses that banks would invest in.”

A greater share of Latino male-owned businesses, 21%, are generating $1 million or more in annual revenue than Latina-owned businesses, at 14%. But 31% of white male-owned businesses are generating that level of revenue, according to the State of Latino Entrepreneurship Report, produced by the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Although he lacks health insurance, Garza said what he would most like the next administration to do is help small-business owners like him know what’s available to reduce costs, such as tax deductions — just like big businesses know how to do.

Latinos overall have made gains in health insurance coverage, homeownership and inflation-adjusted wages under the Biden administration. But one of this year’s election takeaways is that those gains weren’t enough to overcome frustrations, especially among Latino men, about high costs and the impact on their families. Their votes in future elections will likely rest on whether they feel the “American dream” is proving true for them.

“It’s abundant and clear to me that they need to see they are valued as a workforce, that they are invested in as a workforce,” Ponjuán said, “that they are given the infrastructure for that success to happen.”

U.S. Hispanics, who are younger than the general population, are driving the growth of the labor force — by 2030, they will account for 1 out of every 5 workers. In interviews before and after the election, Latino men repeatedly said they want relief from the rising cost of living and more job and business opportunities.

While Hispanic men overall are doing better than Latinas and other groups in some quality-of-life measures, they lag behind white and other men in many areas.

“The [next] administration has a big, big task, especially because they have the House and Senate. President Trump can’t afford to not deliver on some of the things that the community really wants,” said Abraham Enriquez, founder and president of Bienvenido US, a conservative Latino advocacy group that helped turn out Hispanic voters for Trump and Republicans.

“What does it mean for a young Hispanic man that is of Mexican descent such as myself?” Enriquez, 29, said. “Homeownership is at the top of my priorities. It’s the one pathway to generational wealth.”

Close to 1 in 10 people in the U.S., about 32 million people, are Hispanic males; the U.S. Latino population is nearly evenly divided between men and women. Latino males are younger than men in the U.S. overall and have a higher participation in the workforce than any other racial group.

NBC News exit polls showed Trump won 55% support from Hispanic men, while a poll for Latino and other progressive groups reported he won 43%.

The story of Hispanic men is a two-part story, especially in the areas of education and income, according to Mark Hugo Lopez, director of race and ethnicity research at the Pew Research Center.

“Hispanic men have made progress, but so did other people too,” Lopez said. “Hispanic men face many pressures, pressures about family, about economics, about roles they are expected to play.”

Hispanic men have seen solid progress in educational attainment: The share of Latino men ages 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree grew at about the same rate as white men over the last two decades, according to Pew.

The college conundrum

Blanco, a hotel sales coordinator, is also a full-time student at Florida International University. He had not wanted to attend college, despite encouragement from his college-educated parents, who moved the family from Caracas in 2010. He hopes to build a career in sales.

“I told my dad before, if he wasn’t paying for it, I probably wouldn’t do it,” he said of attending college. “I don’t see the point of it in my specific industry — I’ve learned more on the jobs than what I learned in any college class.”

Living at home, he’s been able to save. His earnings at his hotel job have ended the days of getting tax refunds; now, he pays income taxes. He hopes Trump and the next Congress will approve tax breaks and cut spending so he can keep more of his money, he said.

Blanco’s initial lack of interest in college is not uncommon. Victor Saénz, an education professor at University of Texas at Austin, and Luis Ponjuán, an associate professor of education at Texas A&M, began focusing their research on Hispanic men 15 years ago, after noticing their college enrollment numbers were dropping while Latinas’ were growing.

Though the same share of Hispanic men and women 25 and older had bachelor’s degrees in 2003, Latinas have been outpacing men since then, though numbers for both have been improving.

“So many young men that we work with feel left behind, abandoned, not like they’re the focal point of our sort of government efforts, whether it’s public education or public policies,” he said.

Early in their research, there were signs that economics were driving the decisions of young men and boys on whether to attend college and what career pathways they were choosing, Saénz said.

“For so many young men, they decide not to go to college because it seems like it’s a waste of time, it’s an opportunity cost. [They] could be going to work and trying to contribute to their family. … Those are very strong drivers for so many young men, and that’s often rooted in their own notion of being a man, right?” Saénz said.

Some Hispanic men are defining college differently. Ponjuán told the story of a Corpus Christi man in his 40s who earned a commercial driver’s license certificate to get a better job and therefore considered himself a college graduate; he told Ponjuán he could now show his son the value of college education.

But Ponjuán warned that some jobs with high concentrations of Latinos become harder to do in middle age.

“Latino men are checking out because they are the labor force for a lot of these jobs that require manual labor and blue-collar workers,” Ponjuán said. “Young men enter these careers, and by the time they reach 34, 35, their bodies give out and they are no longer able to go into management, because they don’t have a degree or they don’t have the skill sets.”

The median age of Hispanic men is 30.6, while the median age for the general population is 38.1.

Hispanic men work in some of the most dangerous jobs, mostly in transportation and construction, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The most recent census of fatal occupational injuries issued by BLS showed Latino workers were 30% more likely to suffer a fatal injury on the job than other workers overall.

Jun Garza, 43, who was born and raised in San Antonio, is part owner of a small construction and remodeling business there. He didn’t finish high school and was on his own at 15. But he had skills in various trades he learned from his father and uncle, who often used him for jobs because “I was a hard worker.”

He recently injured himself falling off a ladder while trimming a tree at his home. A light bulb went off that “this is not something I’ll be able to do my whole life,” he said; the work has already taken a toll on his body. “I’m not super old, but I will be older, and when I’m too old, they may not want to hire me.”

Garza is now earning his GED and hopes to earn a construction manager certification through community college.

Like Garza, some Hispanic men are using their blue-collar skills to start their own contracting, landscaping, restaurant and other businesses.

“Latinos are starting small businesses out of necessity,” said Juan Proaño, an entrepreneur and the CEO of League of United Latin American Citizens, the nation’s oldest Latino advocacy group. “When they can’t find a job to support their families, they venture out to start one. The problem is they have to finance to grow that business to scale. While there are a lot of Latino startups, there are not a lot of scalable businesses, businesses that banks would invest in.”

A greater share of Latino male-owned businesses, 21%, are generating $1 million or more in annual revenue than Latina-owned businesses, at 14%. But 31% of white male-owned businesses are generating that level of revenue, according to the State of Latino Entrepreneurship Report, produced by the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Although he lacks health insurance, Garza said what he would most like the next administration to do is help small-business owners like him know what’s available to reduce costs, such as tax deductions — just like big businesses know how to do.

Latinos overall have made gains in health insurance coverage, homeownership and inflation-adjusted wages under the Biden administration. But one of this year’s election takeaways is that those gains weren’t enough to overcome frustrations, especially among Latino men, about high costs and the impact on their families. Their votes in future elections will likely rest on whether they feel the “American dream” is proving true for them.

“It’s abundant and clear to me that they need to see they are valued as a workforce, that they are invested in as a workforce,” Ponjuán said, “that they are given the infrastructure for that success to happen.”

Comments( 0 )

0 0 949

0 0 388

0 0 989

0 0 825