Trump Transition: President-Elect Names Gas Executive as Energy Secretary

Posted on 11/17/2024

In a video posted on LinkedIn last year, Mr. Wright declared, “There is no climate crisis, and we’re not in the midst of an energy transition either.”

Mr. Wright, who has no government experience, caught the attention of Mr. Trump in part through his appearances on Fox News. He also appears frequently on podcasts and social media videos, often using language and imagery associated with progressive causes to link oil and gas with issues like the fight for women’s equality.

Mr. Trump announced Mr. Wright’s appointment in a statement and praised him as a “leading technologist and entrepreneur in energy.” He said in addition to leading the Energy Department, Mr. Wright would also be a member of the newly formed council of national energy.

“He has worked in nuclear, solar, geothermal, and oil and gas,” Mr. Trump wrote, referring to Mr. Wright. “Most significantly, Chris was one of the pioneers who helped launch the American shale revolution that fueled American energy independence, and transformed the global energy markets and geopolitics.”

Mr. Wright is close to Harold G. Hamm, the billionaire founder of Continental Resources who donated nearly $5 million to Mr. Trump since 2023 and is playing a role in the transition.

Mr. Wright was a director of the Domestic Energy Producers Alliance, a lobbying group that Mr. Hamm founded. The Wall Street Journal described the alliance as a “counterweight” to larger oil industry groups that recognize that climate change is caused by human activity and support some action to address it.

Mr. Hamm told Hart Energy, an online publication, that Mr. Wright was his top choice to lead the Energy Department.

In August, Mr. Wright’s wife, Liz Wright, co-hosted a fund-raiser in Montana for Mr. Trump. Campaign finance records show that Chris Wright and Liz Wright donated $175,000 apiece to Mr. Trump’s joint fund-raising campaign committee, called Trump 47.

The core mission of the Energy Department is ensuring the safety of the country’s nuclear arsenal. But under President Biden, the agency has also played a large role in leading the energy transition away from fossil fuels and toward wind, solar, nuclear and other forms of noncarbon energy.

As one of his first tasks, Mr. Wright is expected to end a Biden administration pause on new liquefied natural gas export terminals. A judge blocked the pause and the Biden administration did approve at least one export permit, but Republicans and the oil and gas industry have accused the administration of deliberately stalling new approvals.

“We look forward to working with him once confirmed to bolster American geopolitical strength by lifting D.O.E.’s pause on L.N.G. permits and ensuring the open access of American energy for our allies around the world,” said Mike Sommers, the president of the American Petroleum Institute, which represents oil companies, in a statement.

Climate activists criticized the selection of a fossil fuel executive at a time when they say the country needs to invest more heavily in clean energy.

“Like his new boss, Donald Trump, Wright denies the threat of the scientifically proven climate crisis,” said Lori Lodes, the executive director of Climate Power, an environmental nonprofit group. She noted that renewable energy was cheaper to produce than fossil fuels, in part because of the Inflation Reduction Act, a 2022 law pumping hundreds of billions of dollars into wind, solar and other clean energy. Mr. Trump wants Congress to repeal it.

“No matter who they voted for, Americans want cheaper, cleaner energy options,” Ms. Lodes said.

Earlier this week Mr. Trump named Gov. Doug Burgum of North Dakota to lead the Interior Department and chair the new national energy council. Mr. Trump said the team “will drive U.S. energy dominance, which will drive down inflation, win the A.I. arms race with China (and others) and expand American diplomatic power to end wars all across the world.”

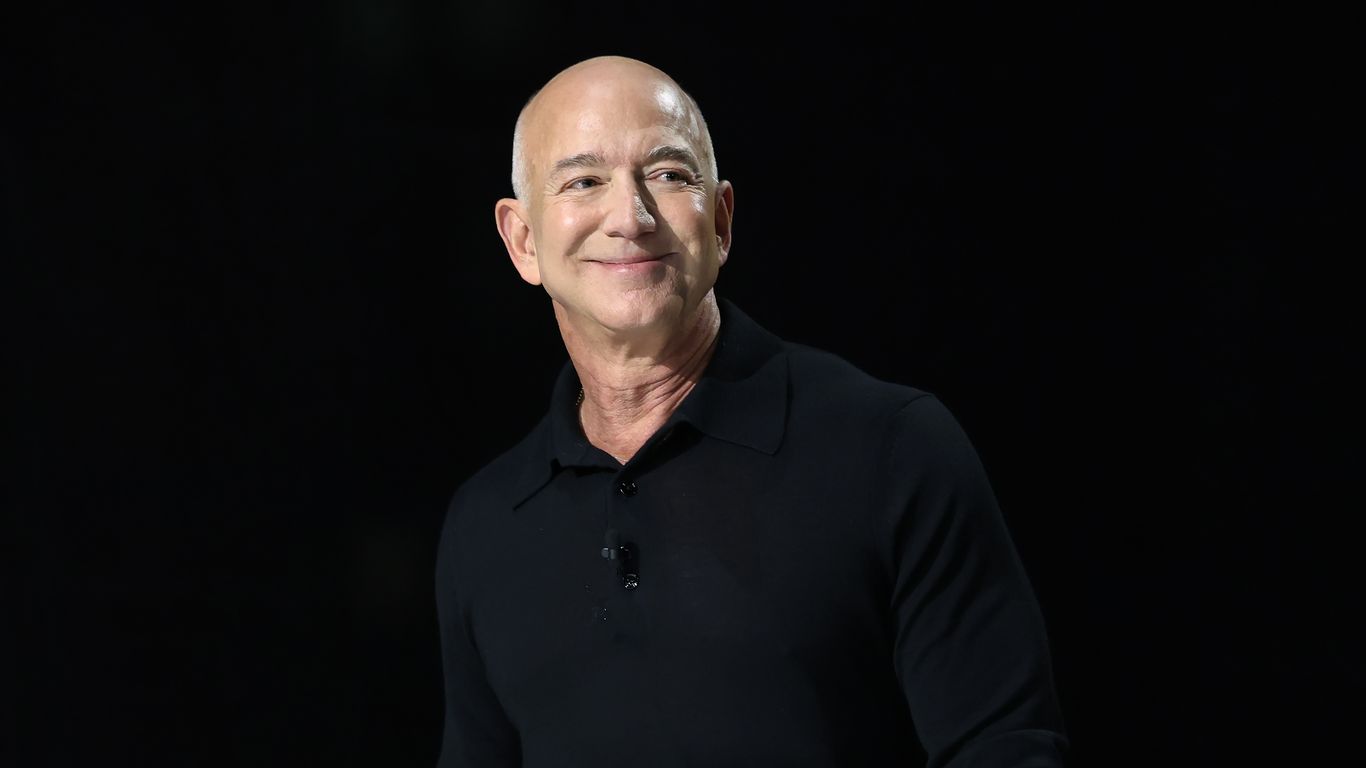

The image of Mr. Wright, who often appears in videos wearing button-down shirts, designer sneakers and no jacket or tie, runs counter to the stereotype of the conservative oil executive.

Yet Mr. Wright’s underlying message lines up almost exactly with Mr. Trump’s: fossil fuels are the critical to growing the economy and climate change is a hoax — or at least, fears of it are overblown.

The president-elect has pledged to “drill, baby drill,” called climate change a scam and promised to erase regulations designed to curb the fossil fuel pollution that is dangerously heating the planet.

Mr. Wright’s rhetoric is less provocative but essentially conveys the same ideas.

On an episode of the podcast “Flipping the Barrel,” Mr. Wright suggested that oil and gas could liberate poor, rural women in developing economies from having to spend hours gathering fuel, including dung, for cookstoves.

“I‘ve been to 55 countries,” he said. “Low income, poor rural areas and traditional societies. Those humans have the same hearts and dreams, want to take care of their kids.”

“A third of humanity doesn’t have access to modern energy, and what’s the biggest impediment to that last third of humanity getting energy right now?” he said. “An irrational and way exaggerated fear of climate change.”

At the United Nations climate summit currently taking place in Baku, Azerbaijan, the main topic is how to help developing nations invest in solar, wind and other clean energy and avoid a reliance on fossil fuels.

Scientists have said that the United States and other major economies must stop developing new oil and gas projects to avert the most catastrophic effects of global warming. The burning of oil, gas and coal is the main driver of climate change.

The current year is shaping up to be the hottest on record, and researchers say the world is on track for dangerous levels of warming this century. Extreme weather linked to climate change is no longer a distant threat; heat waves, floods, drought and hurricanes have caused death and destruction across the globe this year.

People familiar with the thinking of Mr. Trump’s transition team said that among Mr. Wright’s appealing qualities was his oft-told “conversion” story about how he grew up believing that consuming too much oil and gas could be dangerous to humanity — and then later discovered the virtues of abundant oil and gas.

In the podcast, he described being told by a physics professor in high school that oil and gas were running out. Later, however, as an engineering student in graduate school, he learned about hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, the technology of injecting water, chemicals and sand at high pressure into rock to release oil and gas inaccessible through conventional drilling. Over the past decade, fracking has created an American oil and gas boom. Environmentalists worry that fracking can contaminate groundwater.

“There’s a whole lot more oil and gas underground than I certainly thought there was,” said Mr. Wright.

Mr. Wright, who studied engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, founded Pinnacle Technologies in 1992, a company focused on providing shale gas extraction services. From 2000 to 2006 he was chairman of Stroud Energy, an early shale gas producer, according to his website. And in 2011, he founded Liberty Energy, a $2.8 billion company that provides fracking equipment and services.

He has also turned his megaphone on Republican senators who are now in charge of the effort to vet and confirm him. Given the G.O.P.’s slim Senate majority, Mr. Gaetz can afford to lose the support of only three Republicans (assuming all Democrats vote against him) if he wants to be confirmed.

So far, at least five have indicated they are skeptical that Mr. Gaetz could win confirmation. They include Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Susan Collins of Maine, Joni Ernst of Iowa, Kevin Cramer of North Dakota and Thom Tillis of North Carolina.

Additionally, Senator John Cornyn of Texas called on Thursday for the release of a House Ethics Committee report into allegations of sexual misconduct, illegal drug use and other accusations against Mr. Gaetz (all of which the former congressman has denied).

Here are the senators who have been the targets of Mr. Gaetz’s jabs, critiques and insults, which could come back to haunt him as he seeks their votes.

Gaetz called Senator Mitch McConnell “dangerous” and “McFailure,” and cheered his retirement from Republican leadership.

Mr. Gaetz has made no secret of his disdain for establishment Republicans, chief among them Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the minority leader. In 2021, after Mr. McConnell gave a speech castigating Mr. Trump for his role in the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol that year, Mr. Gaetz called Mr. McConnell “dangerous,” saying during an interview on Fox News that he was trying to “purge Trumpism from our movement.”

This year, the former Florida congressman branded Mr. McConnell “McFailure” and even suggested that Senate Republicans should stage a coup of their leader as he had done of Mr. McCarthy.

When Mr. McConnell announced he would be stepping down from his leadership post, Mr. Gaetz rejoiced on social media.

Mr. McConnell has not publicly stated whether he would support a Gaetz nomination.

Gaetz called Senator Markwayne Mullin “a disgrace to the Republican Party.”

Mr. Gaetz has quarreled publicly numerous times with Senator Markwayne Mullin, an Oklahoma Republican and former House colleague who has accused Mr. Gaetz of showing sexually explicit photos and videos of underage girls to colleagues on the House floor. Mr. Gaetz has denied it.

The two men have traded insults in TV interviews and on social media. Mr. Mullin has described Mr. Gaetz as not “a principled individual” and asserted that, “Matt Gaetz is about watching out for himself, and that’s it.”

In a separate tiff over allegations that Mr. Mullin had violated insider trading rules, Mr. Gaetz called him a “disgrace to the Republican Party.”

But since the news of Mr. Gaetz’s nomination broke, Mr. Mullin has made an about-face. He said that even though the two men had their differences, “I completely trust President Trump’s decision making on this one,” Mr. Mullin told CNN’s Jake Tapper. At the same time though, Mr. Mullin said Mr. Gaetz would have to “sell himself” to the Senate.

“There’s a lot of questions that are going to be out there. He’s got to answer those questions, and hopefully he’s able to answer the questions right. And if he can, then we’ll go through the confirmation process.”

Gaetz suggested that Senator Thom Tillis had been untruthful.

Mr. Gaetz in 2020 heavily criticized Mr. Tillis, the Republican Senator from North Carolina, for refusing to call for the resignation of Richard Burr, then a fellow senator from North Carolina who has since left Congress, after Mr. Burr was accused of violating insider trading laws.

“Real leaders tell the truth, Senator Tillis,” Mr. Gaetz wrote on social media.

Mr. Tillis said this week that he was doubtful Mr. Gaetz could get confirmed.

“I think he’s got a lot of work to do to get 50” votes, Mr. Tillis said of Mr. Gaetz, The Associated Press reported. “I’m sure it will make for a popcorn-eating confirmation hearing. Mr. Gaetz and I have jousted on certain issues between the House and the Senate.”

Gaetz opposed Senator-elect Tim Sheehy of Montana for being McConnell’s pick.

Mr. Gaetz came out against Republican Tim Sheehy in Montana’s Senate primary, deriding him as “Mitch McConnell’s choice” to challenge the Democrat, Senator, Jon Tester.

Mr. Gaetz instead backed his House colleague, Representative Matt Rosendale, who dropped his bid not long after starting it.

Mr. Sheehy has not spoken publicly about whether he would vote to confirm Mr. Gaetz.

Gaetz mocked Senator-elect John Curtis of Utah as “Mitt Romney without good hair.”

Mr. Gaetz also campaigned against Representative John Curtis of Utah in the Republican primary for Senate in that state for the seat vacated by Senator Mitt Romney, who is retiring.

“John Curtis is Mitt Romney without good hair,” Gaetz said at a campaign event in Riverton, Utah, where he endorsed the mayor, Trent Staggs as the “America First” conservative who should win.

“I need Republicans who will actually fight,” Mr. Gaetz told The Salt Lake Tribune after the event. “And what I’ve seen in John Curtis for the last several years in the House has been weakness — or a willingness to prioritize foreign interests abroad, special interests in the halls of Washington.”

Mr. Curtis has also made no public comment about Mr. Gaetz’s nomination.

Gaetz backed Senator Rick Scott but is now cozying up to Senator John Thune.

In recent days, Mr. Gaetz has changed his tone considerably in what appears to be a last-ditch effort at diplomacy and courtesy. On Friday, Mr. Gaetz took to social media to praise Senator John Thune, Republican of South Dakota, who was elected this week as majority leader for the new Congress.

Days earlier, Mr. Gaetz had urged senators to vote for Senator Rick Scott, a fellow Floridian and the preferred candidate of the MAGA right, as their next leader. He implied that a vote for Mr. Thune or Mr. Cornyn, the two establishment figures in the race to succeed Mr. McConnell, would mean more of the same in the Senate.

Neither Mr. Thune nor Mr. Cornyn has said whether they will support Mr. Gaetz. Mr. Cornyn, a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, which has jurisdiction over Justice Department nominees, has said that in order to properly vet Mr. Gaetz for the post, senators must see the House Ethics Committee report, and that he would be open to issuing a subpoena for it if necessary.

Washington is far different, too. The Republicans who stymied some of Mr. Trump’s first-term agenda are now dead, retired or Democrats. And the Supreme Court, with three justices appointed by the former president, has proved how far it will go in bending to his will.

As they face this tough political landscape, Democratic officials, activists and ambitious politicians are seeking to build their second wave of opposition to Mr. Trump from the places that they still control: deep-blue states.

Democrats envision flexing their power in these states to partly block the Trump administration’s policies — for example, by refusing to enforce immigration laws — and to push forward their vision of governance by passing state laws enshrining abortion rights, funding paid leave and putting in place a laundry list of other party priorities.

Some of the planning in blue states began in 2023 as a potential backstop if Mr. Trump won, according to multiple Democrats involved in different efforts. The preparations were largely kept quiet to avoid projecting public doubts about Democrats’ ability to win the election.

“States in our system have a lot of power — we’re entrusted with protecting people, and we’re going to do it,” said Keith Ellison, the attorney general of Minnesota, who said his office had been preparing for Mr. Trump’s potential return to power for more than a year. “They can expect that we’re going to show up every single time when they try to run over the American people.”

The Democratic effort will rely on the work of hundreds of lawyers, who are being recruited to combat Trump administration policies on a range of Democratic priorities. Already, advocacy groups have begun workshopping cases and recruiting potential plaintiffs to challenge expected regulations, laws and administrative actions starting on Day 1.

Democracy Forward, a legal group that formed after Mr. Trump won in 2016, has built a multimillion-dollar war chest and marshaled more than 800 lawyers to press a full-throated legal response across a wide range of issues.

“No one was running to the courthouse on a range of things that matter to people in communities,” said Skye Perryman, the group’s chief executive, describing the opposition effort during Mr. Trump’s first term. “Resistance this time is a lot more about collective power building. It’s using the law and using litigation.”

Staff members hired by the party have also begun digging up dirt on Mr. Trump’s future administration. Researchers at the Democratic National Committee and American Bridge, a prominent Democratic super PAC, are compiling dossiers on the earliest picks for his White House and cabinet.

At the federal level, Democrats will have little ability to pass laws or stop Mr. Trump’s agenda. So much of the focus will be on the party’s 23 governors, many of whom are jockeying to be the face of the next anti-Trump movement.

Disagreements over how — and whether — to take on Mr. Trump have already emerged. Govs. Gavin Newsom of California and JB Pritzker of Illinois have taken a more confrontational stance, mobilizing their Democratic-controlled legislatures to gird their states against the future Trump administration.

But others, including Gov. Phil Murphy of New Jersey, have signaled that they will seek areas where they can work with the new administration. Mr. Murphy called Mr. Trump to congratulate him on his victory and plans to attend his inauguration in January. (Mr. Newsom tried to speak with the president-elect this past week, but the call was not returned, he said on his podcast, Politickin’.)

“It’s a combination of fight where you need to fight, and that includes everything — legal action, a bullhorn, peaceful protests and civil disobedience,” Mr. Murphy said of his approach. “And then at the same time, we can’t close off the opportunity to find common ground.”

The Democratic fight for influence

Some of the first maneuvering by top Democrats began this past week, when Mr. Pritzker and Gov. Jared Polis of Colorado announced the formation of a group called Governors Safeguarding Democracy. Its unveiling followed several days of behind-the-scenes drama, as several fellow Democratic governors declined to join the group, at least for now.

A draft news release listed six other governors as members of the coalition led by Mr. Pritzker and Mr. Polis. But four of them — Andy Beshear of Kentucky, Maura Healey of Massachusetts, Michelle Lujan Grisham of New Mexico and Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania — declined to join, according to people briefed on the discussions. Govs. Tony Evers of Wisconsin and Josh Green of Hawaii were also named on the draft news release, but neither has yet agreed to join the group.

Alex Gough, a spokesman for Mr. Pritzker, said that the group had been working with 20 governors’ offices but that “not all of these governors wish to be named publicly at this time for understandable reasons, including the potential threats states are facing.”

Mr. Murphy said he had been approached to join the Pritzker group, as well, but declined, explaining that he was focused on New Jersey until his term ends in early 2026. He said he had also declined to run to lead the Democratic National Committee after holding a series of conversations about entering that race, which is expected to have its first candidates enter by early next week.

The election to lead the party, expected to be held sometime in early 2025, will be an insular contest decided by the 447 members of the D.N.C. Those who have had conversations with party members and prominent Democrats about running include Ken Martin, the Minnesota Democratic chairman; Ben Wikler, the Wisconsin Democratic chairman; Michael Blake, a former New York State Assembly member; Mitch Landrieu, a former Biden administration official who also served as mayor of New Orleans; and Stacey Abrams, who twice ran for governor of Georgia.

“My last 10 days or so have been people asking me, am I running for D.N.C. chair or am I running for New York City mayor?” said Mr. Blake, who was a party vice chair during Mr. Trump’s first term and lost races for Congress and New York City’s public advocate. “I am seriously considering both.”

Joshua Karp, a spokesman for Ms. Abrams, said she had “made no calls and has told people she is not interested in seeking the post.”

Resistance rooted in the law

Much of the party’s new approach remains unsettled. Starting on Sunday night, liberal advocacy organizations will present their strategies at the fall meeting of the Democracy Alliance, a private gathering of some of the party’s richest donors.

The panels range from sweeping subjects — “Making Meaning and Meeting the Moment: Resistance and Reorienting” and “It’s Time to Resist: The Fight Against Project 2025” — to more focused discussions about abortion rights, immigration, racial justice, taxes, countering disinformation and other issues, according to a draft agenda.

Presenters include leaders of prominent left-leaning groups; Democratic politicians like Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Representative Pramila Jayapal of Washington and Representative Ro Khanna of California; and philanthropists like Alex Soros.

Democrats have a growing belief that their efforts must extend beyond the political sphere, trying to go on offense in a splintered media environment where conservatives have amassed more influence. One new liberal dark-money group began prospecting for donors with a pitch that it would unearth unflattering revelations about the Murdoch family and Elon Musk — both pro-Trump media magnates.

The group, called the Two Plus Two Coalition, plans to “target the hidden sources of disinformation and expose them for what they are,” according to a donor prospectus being circulated this past week. The group asked donors for a minimum investment of $1 million, and was aiming for an annual budget of $10 million to $15 million.

The group’s senior adviser, Rick Wilson, a former Republican operative who was a co-founder of the Lincoln Project, said in an interview on Thursday that his organization would operate as an opposition research firm but with a military-grade intelligence-gathering operation that went far beyond the document vetting typical of a political campaign.

“A lot of people in the center and on the left have for a long time sort of bemoaned Fox, but they haven’t done anything about it,” Mr. Wilson said.

Trying to emulate Republicans

In some ways, the new Democratic strategy resembles what Republicans have done during President Biden’s administration.

Over the last four years, Republican governors and state legislatures pursued an agenda that flouted the administration by taking steps to restrict abortion rights, limit transgender rights, ban diversity programs and pursue other conservative priorities. Govs. Ron DeSantis of Florida and Greg Abbott of Texas transported migrants to liberal cities thousands of miles away, forcing immigration to the forefront in places far from the border and helping the Trump campaign capitalize on the issue.

Some Democrats hope to similarly leverage their state power for national impact. In January, two Democratic strategists — Arkadi Gerney and Sarah Knight — circulated a private memo arguing that the party’s top donors should invest more heavily in transforming Democratic-controlled states into new centers of liberal influence.

A second Trump administration, they worried, would be met with far less outrage from the public and more fatigue from Democratic voters. Those factors could leave liberal states playing an even more crucial role, they argued.

Since then, they have been working to better coordinate policy across liberal states, and are urging ambitious Democrats to focus on local efforts.

“Emerging policy experts and political organizers who want to make a difference — don’t go to Washington,” Mr. Gerney said in an interview this past week. “Join the people in Albany, Springfield and Lansing who are working to not only defend against overreach by Trump, but to aggressively make blue and purple states great places to work, live and raise families.”

Kenneth P. Vogel contributed reporting from Washington.

On Tuesday, Mr. Trump tapped two loyal supporters to help find ways to carve up the budget: Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, and Vivek Ramaswamy, a former pharmaceutical executive who was once Mr. Trump’s rival for the Republican presidential nomination. Mr. Trump said the two would lead a new Department of Government Efficiency that would drive “drastic change.”

Mr. Trump has not set a dollar amount that he wants the commission to cut from the federal budget. Mr. Musk has.

After Mr. Trump promised on the campaign trail to tap Mr. Musk to head an efficiency commission, the entrepreneur said it could cut “at least $2 trillion” from the $6.75 trillion federal budget, without providing many details about how that could be done. Mr. Musk also said that the 400-plus federal agencies should be pared down to 99 or fewer, though a massive reduction in the number of agencies would require congressional approval.

In an acknowledgment of just how big of a challenge this poses, Mr. Trump said the new effort could be the “Manhattan project of our time” — a comparison to the resources put into developing the U.S. atomic weapons program during World War II.

What did Mr. Trump ask the commission to do?

Mr. Trump said its mission would be to help the administration “dismantle Government Bureaucracy, slash excess regulations, cut wasteful expenditures and restructure Federal Agencies.” He gave it until July 2026 to finish its work.

The commission will operate outside the government, but will provide guidance and work with the White House budget office, Mr. Trump said.

It’s not clear who will pay for the commission’s staff, or if they will be paid at all: Mr. Musk said in a recent post on X that the “compensation is zero.” The “department” already has an account on X, Mr. Musk’s social-media platform, and Thursday said it was seeking “super high-IQ small-government revolutionaries willing to work 80+ hours per week on unglamorous cost-cutting.” The post implied that Mr. Musk already had some staff working on the project, to winnow down the applicants. “Elon & Vivek will review the top 1% of applicants,” it said.

Can the administration cut $2 trillion in spending?

Despite Mr. Musk’s confidence, there are no easy options.

It’s not hard to find questionable spending in the federal budget. Medicare and Medicaid alone spent $100 billion on fraud and erroneous payments last year. But fraudulent payments are hard (and expensive) to screen out. And finding $2 trillion in savings would be thorny without cutting programs that Congress or Mr. Trump would want to protect.

Here’s the math, based on the 2023 budget: About a third of federal spending went to Medicare and Social Security, programs that aid older Americans. Mr. Trump has said explicitly that he will not cut those. Another 13 percent of the budget went to national defense. Based on his track record, Mr. Trump seems unlikely to make major cuts there, either. He massively boosted military spending in his first term, and has promised to “strengthen and modernize” the military in his second.

Another 10 percent of federal spending went to pay interest on the government’s existing debts. Mr. Musk has already cited that as an area of wasteful spending, recirculating an X post from his America PAC that identified interest payments as something the commission could “fix.” But it would be a risky place to pursue any cuts. The government already committed to making these payments, when it first borrowed the money. If the U.S. suddenly stopped paying them, the result could be a default that creates higher interest rates for average Americans and a potential recession.

What’s left?

That leaves about 40 percent of the budget. Cabinet agencies. Veterans’ benefits. Medicaid, which provides health care for the poor and disabled. Cutting $2 trillion from this sector alone would require huge cutbacks in services that Americans rely on. In the past, both Mr. Trump and Republicans in Congress have called for cuts — even large ones — to some of these programs. But they’ve shown no appetite for chopping them on the scale Mr. Musk has promised. Even the Department of Education, a top target for conservatives this year, supports school districts across the country and has allies on both sides in Congress.

“To eliminate a third of the government, you would have to dramatically eliminate full functions of the federal government,” said Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the right-leaning Manhattan Institute. “You would have to dramatically scale back programs like Social Security, Medicare and defense and veterans. It’s not going to happen.”

Sharon Parrott, president of the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said she worried that the point of the effort was not to reach Mr. Musk’s $2 trillion goal, but rather to change the terms of Washington’s budget debate. She said that Mr. Musk could allow Congress to decimate liberal priorities like education spending, by labeling them as wasteful.

“Any attempt to paint government writ large as rife with waste, as highly inefficient, and as unimportant, can be used in ways that are very damaging,” Ms. Parrott said.

Could Mr. Trump just defy Congress, and refuse to pay for things he thinks are wasteful?

By law, no.

Typically, the president’s role in the budget process is to propose a budget, then wait for Congress to decide what to spend. A 1974 law limits the president’s ability to refuse to spend funds after Congress has appropriated them (that refusal is called “impoundment” in Washington). Presidents can only refuse to spend money if Congress itself approves.

But Mr. Trump has reportedly considered declining to spend the money anyway, despite that law. Some Trump allies have suggested that the 1974 law is unconstitutional. So Mr. Trump could defy Congress, in the belief that he will win an eventual court challenge.

Could the administration slash the federal work force?

The federal government employs roughly 2.3 million civilian workers across the country, according to the most recent data from the Office of Personnel Management. About 85 percent of those employees live outside the Washington metro area.

Mr. Trump could try to reinstitute Schedule F, an executive order he issued late in his first term that would have empowered his administration to strip job protections from many career federal employees and make them more like political appointees who can be fired at will. President Biden revoked the order and his administration finalized a rule this spring that makes it harder to reinstate.

But firing thousands of employees risks impairing critical functions of the government, such as keeping airplanes from colliding and electrical grids from going dark. Mr. Trump could also find it difficult to drastically scale back the federal work force without cutting resources at agencies that support defense and national security.

More than 60 percent of federal civilian workers are employed by the Departments of Defense, Veterans Affairs and Homeland Security, which includes border control, itself a top priority of Mr. Trump’s. The Defense Department makes up the largest share, employing about 34 percent of the work force. The Department of Veterans Affairs employs 21 percent.

Even if Mr. Trump could shut down the Education Department, that would not make a huge dent. The department employs only 0.2 percent of all federal civilian workers, according to Office of Personnel Management data.

The federal work force has not dramatically expanded over the past few decades, whereas the total U.S. population has grown substantially. In 1945, the civilian work force represented about 2.5 percent of the entire population, according to analysis from the Partnership for Public Service, a nonpartisan group. In 2023, that figure was about 0.6 percent.

That is in part because the federal government has relied more on contractors over the years, said Donald F. Kettl, a former dean of the University of Maryland School of Public Policy.

How much does the government spend on federal employees?

In fiscal year 2023, the federal government spent more than $358 billion on pay and benefits for civilian workers in the executive branch.

The government also spends billions of dollars on contracts with outside companies and organizations each year. In fiscal year 2023, the federal government committed about $759 billion on contracts for services and products, according to a Government Accountability Office analysis.

The amount spent on contracts has consistently grown over time. In 2013, for instance, the federal government spent $476.2 billion on goods and services from contractors, according to data from the Office of Management and Budget.

There could be places for Mr. Trump and the commission to cut the work force, but the challenges that come with scaling back could make it difficult to see substantial savings.

“While there may be savings to be had by cutting government employees, it will not be a significant amount that makes much of a dent in the budget deficit,” Mr. Riedl said.

Hasn’t this kind of commission been tried before?

Repeatedly.

As far back as Theodore Roosevelt, presidents have set up commissions to streamline the federal government. In the 1980s, President Reagan gave the task to businessman J. Peter Grace, who recommended 2,478 reforms. In the 1990s, Vice President Al Gore led a “national partnership for reinventing government,” which recommended eliminating 250,000 middle managers from the executive branch.

Both efforts produced some real-world cuts in government, but fell short of their broadest ambitions. They were often led by outsiders, who struggled to work within the slow-moving machinery of government or to sway legislators.

“The fundamental changes need to be done through Congress,” said Tom Schatz, who leads the budget-watchdog nonprofit Citizens Against Government Waste.

That means Mr. Musk and Mr. Ramaswamy likely will not need to win just one political fight to cut $2 trillion, but potentially hundreds or thousands of fights.

“Every program has a constituency. And the constituency in favor of spending money has always been stronger than those that want to reduce spending,” Mr. Schatz said.

Two years later, after Mr. Bush’s bid to privatize Social Security imploded without ever even coming up in Congress and exhaustion with the Iraq war set in, it was instead the president who was spent. Democrats took back Congress, and the governing trifecta Mr. Bush had trumpeted was gone.

The same thing then happened to Barack Obama, Donald J. Trump and Joseph R. Biden Jr. as they gained supremacy in Washington only to see it slip away after two years of aggressively pressing their agenda, with mixed results.

As they prepare for their latest stint in power, congressional Republicans are fully aware from recent history that they may have only two years to accomplish what they want without interference from pesky Democrats before facing a political reckoning. And even those two years could be perilous, with party divisions and small majorities complicating their work and voters expecting big things given their unified control in Washington.

“We’ve got a two-year window of opportunity,” said Senator John Cornyn, Republican of Texas. “It’s going to be hard.”

The fleeting nature of the trifecta has been a regular topic of discussion among Republicans in their private meetings in recent days as they returned to Washington after their election triumph.

Trifectas can be great for the ruling party and provide an opening in often-gridlocked Washington to push through its top priorities. Mr. Obama was able to put in place a sweeping economic stimulus package in 2009 and the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Mr. Trump secured a trillion-dollar-plus tax cut. And Mr. Biden pushed through huge pandemic relief bills and major infrastructure legislation. Two years can produce a lot of change.

Trifectas can also seem daunting and demoralizing to the party out of power, as Republicans experienced in January 2009 when Congress convened with Democrats approaching a filibuster-proof 60 votes in the Senate and holding a huge majority in the House. Republicans feared they might never see power again.

But trifectas can also be transitory, with the legislative efforts done largely along partisan lines and the cycles of politics prompting an inevitable backlash the next time voters weigh in on Congress.

That seeming insurmountable Democratic wall that Republicans confronted in early 2009 was demolished in 2010 when House Republicans gained more than 60 seats in Mr. Obama’s first midterm election and Senate Republicans began their climb back to the majority, though they would not recapture it until 2014.

“The American way is don’t give absolute power to anyone,” said Senator Richard Blumenthal, Democrat of Connecticut. “Don’t give it all to one party or person. We are the checks-and-balances nation. That’s the core of what the founders believed and is in our DNA.”

Trifectas used to be more common when Democrats had an extended streak of control of both the Senate and the House after the Great Depression. But political fortunes began to shift more regularly beginning in the 1990s.

President Bill Clinton had a trifecta during his first two years in office, but it collapsed under the weight of a failed effort to overhaul health care policy and Democratic arrogance in the House, leading Republicans to win a takeover of the House in 1994 after 40 years in the wilderness. In the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, Mr. Bush actually had four years of a trifecta from 2003 to 2007, but it has been two-year intervals since then.

One explanation is that holding unified power in Washington tends to spur a drive by the party in control to push the policy envelope as far as possible and make it difficult, if not impossible, for those in the other party to back the resulting legislation.

That was the case in the fight over the Affordable Care Act in 2009 and 2010, when Republicans capitalized on public unease over the legislation to attack Democrats, even though the policy approach had been built on ideas that originated with the G.O.P. They were able to make the case that Democrats were steamrolling them and imposing a new health care regime on the public along party lines.

Then, when Republicans assembled their own trifecta during the first two years of the Trump administration, they invested much of their time and energy in trying to undo the health care law. They ultimately failed, wasting much of their precious time in full control of the government and drawing a rebuke in 2018 from voters who now liked the health care law.

Republicans say they learned plenty from their last experience with unified power and plan to get out of the gate quickly with a torrent of legislation and nominees to take advantage of what could be a brief moment in political time.

And with Republicans all over Washington tossing around the word “mandate” very freely in the wake of the election, it is pretty clear that their big plans do not include trying to win Democratic support.

“We do have the mandate,” Speaker Mike Johnson told reporters this week, saying he anticipated “the most consequential Congress in the modern era, the most consequential administration in the modern era.”

To Democrats still licking their wounds, that sounds like overreach in the making that could ultimately accrue to their political benefit in two years — though of course there is always the possibility that Republicans could do such a good job that voters opt to keep the trifecta going.

Democrats doubt that.

“Restraint is one of the more difficult leadership qualities to exercise, and I have seen very little appetite for it on the Trump side,” said Senator Peter Welch, Democrat of Vermont.

Even as they get ready for a fast start, Republicans accept that their trifecta is tenuous, particularly with what is certain to be a very small majority in the House. That gives Democrats an excellent shot of knocking them out of power in 2026, a point in the political cycle that historically favors the party on the outs.

“It is pretty fragile,” Senator Kevin Cramer, Republican of North Dakota, conceded of his party’s total hold on things.

With the clock already ticking, Republicans know they have to plunge ahead and notch whatever victories they can, recognizing the reality that two years in full control is about as much as they should expect.

“It means,” Mr. Cramer said, “that we just have to do our thing.”

Mr. Wright, who has no government experience, caught the attention of Mr. Trump in part through his appearances on Fox News. He also appears frequently on podcasts and social media videos, often using language and imagery associated with progressive causes to link oil and gas with issues like the fight for women’s equality.

Mr. Trump announced Mr. Wright’s appointment in a statement and praised him as a “leading technologist and entrepreneur in energy.” He said in addition to leading the Energy Department, Mr. Wright would also be a member of the newly formed council of national energy.

“He has worked in nuclear, solar, geothermal, and oil and gas,” Mr. Trump wrote, referring to Mr. Wright. “Most significantly, Chris was one of the pioneers who helped launch the American shale revolution that fueled American energy independence, and transformed the global energy markets and geopolitics.”

Mr. Wright is close to Harold G. Hamm, the billionaire founder of Continental Resources who donated nearly $5 million to Mr. Trump since 2023 and is playing a role in the transition.

Mr. Wright was a director of the Domestic Energy Producers Alliance, a lobbying group that Mr. Hamm founded. The Wall Street Journal described the alliance as a “counterweight” to larger oil industry groups that recognize that climate change is caused by human activity and support some action to address it.

Mr. Hamm told Hart Energy, an online publication, that Mr. Wright was his top choice to lead the Energy Department.

In August, Mr. Wright’s wife, Liz Wright, co-hosted a fund-raiser in Montana for Mr. Trump. Campaign finance records show that Chris Wright and Liz Wright donated $175,000 apiece to Mr. Trump’s joint fund-raising campaign committee, called Trump 47.

The core mission of the Energy Department is ensuring the safety of the country’s nuclear arsenal. But under President Biden, the agency has also played a large role in leading the energy transition away from fossil fuels and toward wind, solar, nuclear and other forms of noncarbon energy.

As one of his first tasks, Mr. Wright is expected to end a Biden administration pause on new liquefied natural gas export terminals. A judge blocked the pause and the Biden administration did approve at least one export permit, but Republicans and the oil and gas industry have accused the administration of deliberately stalling new approvals.

“We look forward to working with him once confirmed to bolster American geopolitical strength by lifting D.O.E.’s pause on L.N.G. permits and ensuring the open access of American energy for our allies around the world,” said Mike Sommers, the president of the American Petroleum Institute, which represents oil companies, in a statement.

Climate activists criticized the selection of a fossil fuel executive at a time when they say the country needs to invest more heavily in clean energy.

“Like his new boss, Donald Trump, Wright denies the threat of the scientifically proven climate crisis,” said Lori Lodes, the executive director of Climate Power, an environmental nonprofit group. She noted that renewable energy was cheaper to produce than fossil fuels, in part because of the Inflation Reduction Act, a 2022 law pumping hundreds of billions of dollars into wind, solar and other clean energy. Mr. Trump wants Congress to repeal it.

“No matter who they voted for, Americans want cheaper, cleaner energy options,” Ms. Lodes said.

Earlier this week Mr. Trump named Gov. Doug Burgum of North Dakota to lead the Interior Department and chair the new national energy council. Mr. Trump said the team “will drive U.S. energy dominance, which will drive down inflation, win the A.I. arms race with China (and others) and expand American diplomatic power to end wars all across the world.”

The image of Mr. Wright, who often appears in videos wearing button-down shirts, designer sneakers and no jacket or tie, runs counter to the stereotype of the conservative oil executive.

Yet Mr. Wright’s underlying message lines up almost exactly with Mr. Trump’s: fossil fuels are the critical to growing the economy and climate change is a hoax — or at least, fears of it are overblown.

The president-elect has pledged to “drill, baby drill,” called climate change a scam and promised to erase regulations designed to curb the fossil fuel pollution that is dangerously heating the planet.

Mr. Wright’s rhetoric is less provocative but essentially conveys the same ideas.

On an episode of the podcast “Flipping the Barrel,” Mr. Wright suggested that oil and gas could liberate poor, rural women in developing economies from having to spend hours gathering fuel, including dung, for cookstoves.

“I‘ve been to 55 countries,” he said. “Low income, poor rural areas and traditional societies. Those humans have the same hearts and dreams, want to take care of their kids.”

“A third of humanity doesn’t have access to modern energy, and what’s the biggest impediment to that last third of humanity getting energy right now?” he said. “An irrational and way exaggerated fear of climate change.”

At the United Nations climate summit currently taking place in Baku, Azerbaijan, the main topic is how to help developing nations invest in solar, wind and other clean energy and avoid a reliance on fossil fuels.

Scientists have said that the United States and other major economies must stop developing new oil and gas projects to avert the most catastrophic effects of global warming. The burning of oil, gas and coal is the main driver of climate change.

The current year is shaping up to be the hottest on record, and researchers say the world is on track for dangerous levels of warming this century. Extreme weather linked to climate change is no longer a distant threat; heat waves, floods, drought and hurricanes have caused death and destruction across the globe this year.

People familiar with the thinking of Mr. Trump’s transition team said that among Mr. Wright’s appealing qualities was his oft-told “conversion” story about how he grew up believing that consuming too much oil and gas could be dangerous to humanity — and then later discovered the virtues of abundant oil and gas.

In the podcast, he described being told by a physics professor in high school that oil and gas were running out. Later, however, as an engineering student in graduate school, he learned about hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, the technology of injecting water, chemicals and sand at high pressure into rock to release oil and gas inaccessible through conventional drilling. Over the past decade, fracking has created an American oil and gas boom. Environmentalists worry that fracking can contaminate groundwater.

“There’s a whole lot more oil and gas underground than I certainly thought there was,” said Mr. Wright.

Mr. Wright, who studied engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, founded Pinnacle Technologies in 1992, a company focused on providing shale gas extraction services. From 2000 to 2006 he was chairman of Stroud Energy, an early shale gas producer, according to his website. And in 2011, he founded Liberty Energy, a $2.8 billion company that provides fracking equipment and services.

He has also turned his megaphone on Republican senators who are now in charge of the effort to vet and confirm him. Given the G.O.P.’s slim Senate majority, Mr. Gaetz can afford to lose the support of only three Republicans (assuming all Democrats vote against him) if he wants to be confirmed.

So far, at least five have indicated they are skeptical that Mr. Gaetz could win confirmation. They include Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Susan Collins of Maine, Joni Ernst of Iowa, Kevin Cramer of North Dakota and Thom Tillis of North Carolina.

Additionally, Senator John Cornyn of Texas called on Thursday for the release of a House Ethics Committee report into allegations of sexual misconduct, illegal drug use and other accusations against Mr. Gaetz (all of which the former congressman has denied).

Here are the senators who have been the targets of Mr. Gaetz’s jabs, critiques and insults, which could come back to haunt him as he seeks their votes.

Gaetz called Senator Mitch McConnell “dangerous” and “McFailure,” and cheered his retirement from Republican leadership.

Mr. Gaetz has made no secret of his disdain for establishment Republicans, chief among them Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the minority leader. In 2021, after Mr. McConnell gave a speech castigating Mr. Trump for his role in the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol that year, Mr. Gaetz called Mr. McConnell “dangerous,” saying during an interview on Fox News that he was trying to “purge Trumpism from our movement.”

This year, the former Florida congressman branded Mr. McConnell “McFailure” and even suggested that Senate Republicans should stage a coup of their leader as he had done of Mr. McCarthy.

When Mr. McConnell announced he would be stepping down from his leadership post, Mr. Gaetz rejoiced on social media.

Mr. McConnell has not publicly stated whether he would support a Gaetz nomination.

Gaetz called Senator Markwayne Mullin “a disgrace to the Republican Party.”

Mr. Gaetz has quarreled publicly numerous times with Senator Markwayne Mullin, an Oklahoma Republican and former House colleague who has accused Mr. Gaetz of showing sexually explicit photos and videos of underage girls to colleagues on the House floor. Mr. Gaetz has denied it.

The two men have traded insults in TV interviews and on social media. Mr. Mullin has described Mr. Gaetz as not “a principled individual” and asserted that, “Matt Gaetz is about watching out for himself, and that’s it.”

In a separate tiff over allegations that Mr. Mullin had violated insider trading rules, Mr. Gaetz called him a “disgrace to the Republican Party.”

But since the news of Mr. Gaetz’s nomination broke, Mr. Mullin has made an about-face. He said that even though the two men had their differences, “I completely trust President Trump’s decision making on this one,” Mr. Mullin told CNN’s Jake Tapper. At the same time though, Mr. Mullin said Mr. Gaetz would have to “sell himself” to the Senate.

“There’s a lot of questions that are going to be out there. He’s got to answer those questions, and hopefully he’s able to answer the questions right. And if he can, then we’ll go through the confirmation process.”

Gaetz suggested that Senator Thom Tillis had been untruthful.

Mr. Gaetz in 2020 heavily criticized Mr. Tillis, the Republican Senator from North Carolina, for refusing to call for the resignation of Richard Burr, then a fellow senator from North Carolina who has since left Congress, after Mr. Burr was accused of violating insider trading laws.

“Real leaders tell the truth, Senator Tillis,” Mr. Gaetz wrote on social media.

Mr. Tillis said this week that he was doubtful Mr. Gaetz could get confirmed.

“I think he’s got a lot of work to do to get 50” votes, Mr. Tillis said of Mr. Gaetz, The Associated Press reported. “I’m sure it will make for a popcorn-eating confirmation hearing. Mr. Gaetz and I have jousted on certain issues between the House and the Senate.”

Gaetz opposed Senator-elect Tim Sheehy of Montana for being McConnell’s pick.

Mr. Gaetz came out against Republican Tim Sheehy in Montana’s Senate primary, deriding him as “Mitch McConnell’s choice” to challenge the Democrat, Senator, Jon Tester.

Mr. Gaetz instead backed his House colleague, Representative Matt Rosendale, who dropped his bid not long after starting it.

Mr. Sheehy has not spoken publicly about whether he would vote to confirm Mr. Gaetz.

Gaetz mocked Senator-elect John Curtis of Utah as “Mitt Romney without good hair.”

Mr. Gaetz also campaigned against Representative John Curtis of Utah in the Republican primary for Senate in that state for the seat vacated by Senator Mitt Romney, who is retiring.

“John Curtis is Mitt Romney without good hair,” Gaetz said at a campaign event in Riverton, Utah, where he endorsed the mayor, Trent Staggs as the “America First” conservative who should win.

“I need Republicans who will actually fight,” Mr. Gaetz told The Salt Lake Tribune after the event. “And what I’ve seen in John Curtis for the last several years in the House has been weakness — or a willingness to prioritize foreign interests abroad, special interests in the halls of Washington.”

Mr. Curtis has also made no public comment about Mr. Gaetz’s nomination.

Gaetz backed Senator Rick Scott but is now cozying up to Senator John Thune.

In recent days, Mr. Gaetz has changed his tone considerably in what appears to be a last-ditch effort at diplomacy and courtesy. On Friday, Mr. Gaetz took to social media to praise Senator John Thune, Republican of South Dakota, who was elected this week as majority leader for the new Congress.

Days earlier, Mr. Gaetz had urged senators to vote for Senator Rick Scott, a fellow Floridian and the preferred candidate of the MAGA right, as their next leader. He implied that a vote for Mr. Thune or Mr. Cornyn, the two establishment figures in the race to succeed Mr. McConnell, would mean more of the same in the Senate.

Neither Mr. Thune nor Mr. Cornyn has said whether they will support Mr. Gaetz. Mr. Cornyn, a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, which has jurisdiction over Justice Department nominees, has said that in order to properly vet Mr. Gaetz for the post, senators must see the House Ethics Committee report, and that he would be open to issuing a subpoena for it if necessary.

Washington is far different, too. The Republicans who stymied some of Mr. Trump’s first-term agenda are now dead, retired or Democrats. And the Supreme Court, with three justices appointed by the former president, has proved how far it will go in bending to his will.

As they face this tough political landscape, Democratic officials, activists and ambitious politicians are seeking to build their second wave of opposition to Mr. Trump from the places that they still control: deep-blue states.

Democrats envision flexing their power in these states to partly block the Trump administration’s policies — for example, by refusing to enforce immigration laws — and to push forward their vision of governance by passing state laws enshrining abortion rights, funding paid leave and putting in place a laundry list of other party priorities.

Some of the planning in blue states began in 2023 as a potential backstop if Mr. Trump won, according to multiple Democrats involved in different efforts. The preparations were largely kept quiet to avoid projecting public doubts about Democrats’ ability to win the election.

“States in our system have a lot of power — we’re entrusted with protecting people, and we’re going to do it,” said Keith Ellison, the attorney general of Minnesota, who said his office had been preparing for Mr. Trump’s potential return to power for more than a year. “They can expect that we’re going to show up every single time when they try to run over the American people.”

The Democratic effort will rely on the work of hundreds of lawyers, who are being recruited to combat Trump administration policies on a range of Democratic priorities. Already, advocacy groups have begun workshopping cases and recruiting potential plaintiffs to challenge expected regulations, laws and administrative actions starting on Day 1.

Democracy Forward, a legal group that formed after Mr. Trump won in 2016, has built a multimillion-dollar war chest and marshaled more than 800 lawyers to press a full-throated legal response across a wide range of issues.

“No one was running to the courthouse on a range of things that matter to people in communities,” said Skye Perryman, the group’s chief executive, describing the opposition effort during Mr. Trump’s first term. “Resistance this time is a lot more about collective power building. It’s using the law and using litigation.”

Staff members hired by the party have also begun digging up dirt on Mr. Trump’s future administration. Researchers at the Democratic National Committee and American Bridge, a prominent Democratic super PAC, are compiling dossiers on the earliest picks for his White House and cabinet.

At the federal level, Democrats will have little ability to pass laws or stop Mr. Trump’s agenda. So much of the focus will be on the party’s 23 governors, many of whom are jockeying to be the face of the next anti-Trump movement.

Disagreements over how — and whether — to take on Mr. Trump have already emerged. Govs. Gavin Newsom of California and JB Pritzker of Illinois have taken a more confrontational stance, mobilizing their Democratic-controlled legislatures to gird their states against the future Trump administration.

But others, including Gov. Phil Murphy of New Jersey, have signaled that they will seek areas where they can work with the new administration. Mr. Murphy called Mr. Trump to congratulate him on his victory and plans to attend his inauguration in January. (Mr. Newsom tried to speak with the president-elect this past week, but the call was not returned, he said on his podcast, Politickin’.)

“It’s a combination of fight where you need to fight, and that includes everything — legal action, a bullhorn, peaceful protests and civil disobedience,” Mr. Murphy said of his approach. “And then at the same time, we can’t close off the opportunity to find common ground.”

The Democratic fight for influence

Some of the first maneuvering by top Democrats began this past week, when Mr. Pritzker and Gov. Jared Polis of Colorado announced the formation of a group called Governors Safeguarding Democracy. Its unveiling followed several days of behind-the-scenes drama, as several fellow Democratic governors declined to join the group, at least for now.

A draft news release listed six other governors as members of the coalition led by Mr. Pritzker and Mr. Polis. But four of them — Andy Beshear of Kentucky, Maura Healey of Massachusetts, Michelle Lujan Grisham of New Mexico and Josh Shapiro of Pennsylvania — declined to join, according to people briefed on the discussions. Govs. Tony Evers of Wisconsin and Josh Green of Hawaii were also named on the draft news release, but neither has yet agreed to join the group.

Alex Gough, a spokesman for Mr. Pritzker, said that the group had been working with 20 governors’ offices but that “not all of these governors wish to be named publicly at this time for understandable reasons, including the potential threats states are facing.”

Mr. Murphy said he had been approached to join the Pritzker group, as well, but declined, explaining that he was focused on New Jersey until his term ends in early 2026. He said he had also declined to run to lead the Democratic National Committee after holding a series of conversations about entering that race, which is expected to have its first candidates enter by early next week.

The election to lead the party, expected to be held sometime in early 2025, will be an insular contest decided by the 447 members of the D.N.C. Those who have had conversations with party members and prominent Democrats about running include Ken Martin, the Minnesota Democratic chairman; Ben Wikler, the Wisconsin Democratic chairman; Michael Blake, a former New York State Assembly member; Mitch Landrieu, a former Biden administration official who also served as mayor of New Orleans; and Stacey Abrams, who twice ran for governor of Georgia.

“My last 10 days or so have been people asking me, am I running for D.N.C. chair or am I running for New York City mayor?” said Mr. Blake, who was a party vice chair during Mr. Trump’s first term and lost races for Congress and New York City’s public advocate. “I am seriously considering both.”

Joshua Karp, a spokesman for Ms. Abrams, said she had “made no calls and has told people she is not interested in seeking the post.”

Resistance rooted in the law

Much of the party’s new approach remains unsettled. Starting on Sunday night, liberal advocacy organizations will present their strategies at the fall meeting of the Democracy Alliance, a private gathering of some of the party’s richest donors.

The panels range from sweeping subjects — “Making Meaning and Meeting the Moment: Resistance and Reorienting” and “It’s Time to Resist: The Fight Against Project 2025” — to more focused discussions about abortion rights, immigration, racial justice, taxes, countering disinformation and other issues, according to a draft agenda.

Presenters include leaders of prominent left-leaning groups; Democratic politicians like Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, Representative Pramila Jayapal of Washington and Representative Ro Khanna of California; and philanthropists like Alex Soros.

Democrats have a growing belief that their efforts must extend beyond the political sphere, trying to go on offense in a splintered media environment where conservatives have amassed more influence. One new liberal dark-money group began prospecting for donors with a pitch that it would unearth unflattering revelations about the Murdoch family and Elon Musk — both pro-Trump media magnates.

The group, called the Two Plus Two Coalition, plans to “target the hidden sources of disinformation and expose them for what they are,” according to a donor prospectus being circulated this past week. The group asked donors for a minimum investment of $1 million, and was aiming for an annual budget of $10 million to $15 million.

The group’s senior adviser, Rick Wilson, a former Republican operative who was a co-founder of the Lincoln Project, said in an interview on Thursday that his organization would operate as an opposition research firm but with a military-grade intelligence-gathering operation that went far beyond the document vetting typical of a political campaign.

“A lot of people in the center and on the left have for a long time sort of bemoaned Fox, but they haven’t done anything about it,” Mr. Wilson said.

Trying to emulate Republicans

In some ways, the new Democratic strategy resembles what Republicans have done during President Biden’s administration.

Over the last four years, Republican governors and state legislatures pursued an agenda that flouted the administration by taking steps to restrict abortion rights, limit transgender rights, ban diversity programs and pursue other conservative priorities. Govs. Ron DeSantis of Florida and Greg Abbott of Texas transported migrants to liberal cities thousands of miles away, forcing immigration to the forefront in places far from the border and helping the Trump campaign capitalize on the issue.

Some Democrats hope to similarly leverage their state power for national impact. In January, two Democratic strategists — Arkadi Gerney and Sarah Knight — circulated a private memo arguing that the party’s top donors should invest more heavily in transforming Democratic-controlled states into new centers of liberal influence.

A second Trump administration, they worried, would be met with far less outrage from the public and more fatigue from Democratic voters. Those factors could leave liberal states playing an even more crucial role, they argued.

Since then, they have been working to better coordinate policy across liberal states, and are urging ambitious Democrats to focus on local efforts.

“Emerging policy experts and political organizers who want to make a difference — don’t go to Washington,” Mr. Gerney said in an interview this past week. “Join the people in Albany, Springfield and Lansing who are working to not only defend against overreach by Trump, but to aggressively make blue and purple states great places to work, live and raise families.”

Kenneth P. Vogel contributed reporting from Washington.

On Tuesday, Mr. Trump tapped two loyal supporters to help find ways to carve up the budget: Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, and Vivek Ramaswamy, a former pharmaceutical executive who was once Mr. Trump’s rival for the Republican presidential nomination. Mr. Trump said the two would lead a new Department of Government Efficiency that would drive “drastic change.”

Mr. Trump has not set a dollar amount that he wants the commission to cut from the federal budget. Mr. Musk has.

After Mr. Trump promised on the campaign trail to tap Mr. Musk to head an efficiency commission, the entrepreneur said it could cut “at least $2 trillion” from the $6.75 trillion federal budget, without providing many details about how that could be done. Mr. Musk also said that the 400-plus federal agencies should be pared down to 99 or fewer, though a massive reduction in the number of agencies would require congressional approval.

In an acknowledgment of just how big of a challenge this poses, Mr. Trump said the new effort could be the “Manhattan project of our time” — a comparison to the resources put into developing the U.S. atomic weapons program during World War II.

What did Mr. Trump ask the commission to do?

Mr. Trump said its mission would be to help the administration “dismantle Government Bureaucracy, slash excess regulations, cut wasteful expenditures and restructure Federal Agencies.” He gave it until July 2026 to finish its work.

The commission will operate outside the government, but will provide guidance and work with the White House budget office, Mr. Trump said.

It’s not clear who will pay for the commission’s staff, or if they will be paid at all: Mr. Musk said in a recent post on X that the “compensation is zero.” The “department” already has an account on X, Mr. Musk’s social-media platform, and Thursday said it was seeking “super high-IQ small-government revolutionaries willing to work 80+ hours per week on unglamorous cost-cutting.” The post implied that Mr. Musk already had some staff working on the project, to winnow down the applicants. “Elon & Vivek will review the top 1% of applicants,” it said.

Can the administration cut $2 trillion in spending?

Despite Mr. Musk’s confidence, there are no easy options.

It’s not hard to find questionable spending in the federal budget. Medicare and Medicaid alone spent $100 billion on fraud and erroneous payments last year. But fraudulent payments are hard (and expensive) to screen out. And finding $2 trillion in savings would be thorny without cutting programs that Congress or Mr. Trump would want to protect.

Here’s the math, based on the 2023 budget: About a third of federal spending went to Medicare and Social Security, programs that aid older Americans. Mr. Trump has said explicitly that he will not cut those. Another 13 percent of the budget went to national defense. Based on his track record, Mr. Trump seems unlikely to make major cuts there, either. He massively boosted military spending in his first term, and has promised to “strengthen and modernize” the military in his second.

Another 10 percent of federal spending went to pay interest on the government’s existing debts. Mr. Musk has already cited that as an area of wasteful spending, recirculating an X post from his America PAC that identified interest payments as something the commission could “fix.” But it would be a risky place to pursue any cuts. The government already committed to making these payments, when it first borrowed the money. If the U.S. suddenly stopped paying them, the result could be a default that creates higher interest rates for average Americans and a potential recession.

What’s left?

That leaves about 40 percent of the budget. Cabinet agencies. Veterans’ benefits. Medicaid, which provides health care for the poor and disabled. Cutting $2 trillion from this sector alone would require huge cutbacks in services that Americans rely on. In the past, both Mr. Trump and Republicans in Congress have called for cuts — even large ones — to some of these programs. But they’ve shown no appetite for chopping them on the scale Mr. Musk has promised. Even the Department of Education, a top target for conservatives this year, supports school districts across the country and has allies on both sides in Congress.

“To eliminate a third of the government, you would have to dramatically eliminate full functions of the federal government,” said Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the right-leaning Manhattan Institute. “You would have to dramatically scale back programs like Social Security, Medicare and defense and veterans. It’s not going to happen.”

Sharon Parrott, president of the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said she worried that the point of the effort was not to reach Mr. Musk’s $2 trillion goal, but rather to change the terms of Washington’s budget debate. She said that Mr. Musk could allow Congress to decimate liberal priorities like education spending, by labeling them as wasteful.

“Any attempt to paint government writ large as rife with waste, as highly inefficient, and as unimportant, can be used in ways that are very damaging,” Ms. Parrott said.

Could Mr. Trump just defy Congress, and refuse to pay for things he thinks are wasteful?

By law, no.

Typically, the president’s role in the budget process is to propose a budget, then wait for Congress to decide what to spend. A 1974 law limits the president’s ability to refuse to spend funds after Congress has appropriated them (that refusal is called “impoundment” in Washington). Presidents can only refuse to spend money if Congress itself approves.

But Mr. Trump has reportedly considered declining to spend the money anyway, despite that law. Some Trump allies have suggested that the 1974 law is unconstitutional. So Mr. Trump could defy Congress, in the belief that he will win an eventual court challenge.

Could the administration slash the federal work force?

The federal government employs roughly 2.3 million civilian workers across the country, according to the most recent data from the Office of Personnel Management. About 85 percent of those employees live outside the Washington metro area.

Mr. Trump could try to reinstitute Schedule F, an executive order he issued late in his first term that would have empowered his administration to strip job protections from many career federal employees and make them more like political appointees who can be fired at will. President Biden revoked the order and his administration finalized a rule this spring that makes it harder to reinstate.

But firing thousands of employees risks impairing critical functions of the government, such as keeping airplanes from colliding and electrical grids from going dark. Mr. Trump could also find it difficult to drastically scale back the federal work force without cutting resources at agencies that support defense and national security.

More than 60 percent of federal civilian workers are employed by the Departments of Defense, Veterans Affairs and Homeland Security, which includes border control, itself a top priority of Mr. Trump’s. The Defense Department makes up the largest share, employing about 34 percent of the work force. The Department of Veterans Affairs employs 21 percent.

Even if Mr. Trump could shut down the Education Department, that would not make a huge dent. The department employs only 0.2 percent of all federal civilian workers, according to Office of Personnel Management data.

The federal work force has not dramatically expanded over the past few decades, whereas the total U.S. population has grown substantially. In 1945, the civilian work force represented about 2.5 percent of the entire population, according to analysis from the Partnership for Public Service, a nonpartisan group. In 2023, that figure was about 0.6 percent.

That is in part because the federal government has relied more on contractors over the years, said Donald F. Kettl, a former dean of the University of Maryland School of Public Policy.

How much does the government spend on federal employees?

In fiscal year 2023, the federal government spent more than $358 billion on pay and benefits for civilian workers in the executive branch.

The government also spends billions of dollars on contracts with outside companies and organizations each year. In fiscal year 2023, the federal government committed about $759 billion on contracts for services and products, according to a Government Accountability Office analysis.

The amount spent on contracts has consistently grown over time. In 2013, for instance, the federal government spent $476.2 billion on goods and services from contractors, according to data from the Office of Management and Budget.

There could be places for Mr. Trump and the commission to cut the work force, but the challenges that come with scaling back could make it difficult to see substantial savings.

“While there may be savings to be had by cutting government employees, it will not be a significant amount that makes much of a dent in the budget deficit,” Mr. Riedl said.

Hasn’t this kind of commission been tried before?

Repeatedly.

As far back as Theodore Roosevelt, presidents have set up commissions to streamline the federal government. In the 1980s, President Reagan gave the task to businessman J. Peter Grace, who recommended 2,478 reforms. In the 1990s, Vice President Al Gore led a “national partnership for reinventing government,” which recommended eliminating 250,000 middle managers from the executive branch.

Both efforts produced some real-world cuts in government, but fell short of their broadest ambitions. They were often led by outsiders, who struggled to work within the slow-moving machinery of government or to sway legislators.

“The fundamental changes need to be done through Congress,” said Tom Schatz, who leads the budget-watchdog nonprofit Citizens Against Government Waste.

That means Mr. Musk and Mr. Ramaswamy likely will not need to win just one political fight to cut $2 trillion, but potentially hundreds or thousands of fights.

“Every program has a constituency. And the constituency in favor of spending money has always been stronger than those that want to reduce spending,” Mr. Schatz said.

Two years later, after Mr. Bush’s bid to privatize Social Security imploded without ever even coming up in Congress and exhaustion with the Iraq war set in, it was instead the president who was spent. Democrats took back Congress, and the governing trifecta Mr. Bush had trumpeted was gone.

The same thing then happened to Barack Obama, Donald J. Trump and Joseph R. Biden Jr. as they gained supremacy in Washington only to see it slip away after two years of aggressively pressing their agenda, with mixed results.

As they prepare for their latest stint in power, congressional Republicans are fully aware from recent history that they may have only two years to accomplish what they want without interference from pesky Democrats before facing a political reckoning. And even those two years could be perilous, with party divisions and small majorities complicating their work and voters expecting big things given their unified control in Washington.

“We’ve got a two-year window of opportunity,” said Senator John Cornyn, Republican of Texas. “It’s going to be hard.”

The fleeting nature of the trifecta has been a regular topic of discussion among Republicans in their private meetings in recent days as they returned to Washington after their election triumph.

Trifectas can be great for the ruling party and provide an opening in often-gridlocked Washington to push through its top priorities. Mr. Obama was able to put in place a sweeping economic stimulus package in 2009 and the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Mr. Trump secured a trillion-dollar-plus tax cut. And Mr. Biden pushed through huge pandemic relief bills and major infrastructure legislation. Two years can produce a lot of change.

Trifectas can also seem daunting and demoralizing to the party out of power, as Republicans experienced in January 2009 when Congress convened with Democrats approaching a filibuster-proof 60 votes in the Senate and holding a huge majority in the House. Republicans feared they might never see power again.

But trifectas can also be transitory, with the legislative efforts done largely along partisan lines and the cycles of politics prompting an inevitable backlash the next time voters weigh in on Congress.

That seeming insurmountable Democratic wall that Republicans confronted in early 2009 was demolished in 2010 when House Republicans gained more than 60 seats in Mr. Obama’s first midterm election and Senate Republicans began their climb back to the majority, though they would not recapture it until 2014.

“The American way is don’t give absolute power to anyone,” said Senator Richard Blumenthal, Democrat of Connecticut. “Don’t give it all to one party or person. We are the checks-and-balances nation. That’s the core of what the founders believed and is in our DNA.”

Trifectas used to be more common when Democrats had an extended streak of control of both the Senate and the House after the Great Depression. But political fortunes began to shift more regularly beginning in the 1990s.

President Bill Clinton had a trifecta during his first two years in office, but it collapsed under the weight of a failed effort to overhaul health care policy and Democratic arrogance in the House, leading Republicans to win a takeover of the House in 1994 after 40 years in the wilderness. In the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, Mr. Bush actually had four years of a trifecta from 2003 to 2007, but it has been two-year intervals since then.

One explanation is that holding unified power in Washington tends to spur a drive by the party in control to push the policy envelope as far as possible and make it difficult, if not impossible, for those in the other party to back the resulting legislation.