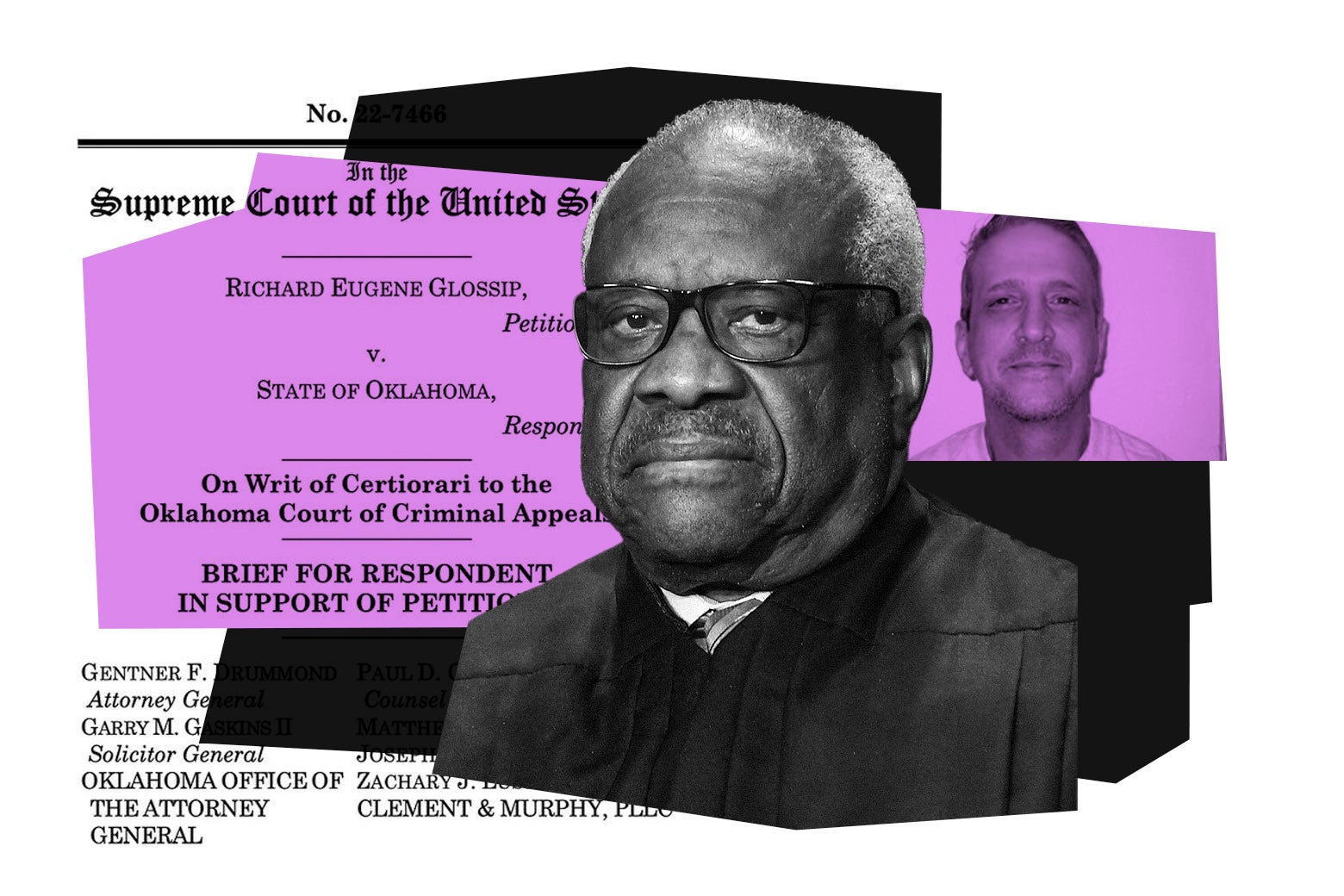

Clarence Thomas Thinks the Real Victims Are Prosecutors Who Engage in Misconduct

Posted on 10/09/2024

The Supreme Court heard arguments on Wednesday in Glossip v. Oklahoma, a death penalty case posing a question so bizarre that its very existence should serve as an indictment for capital punishment: Can courts force a state to execute a possibly innocent prisoner when the state itself doesn’t want to? Richard Glossip, the petitioner, argues that prosecutors concealed key evidence and allowed false testimony at his trial, securing a wrongful conviction. Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner F. Drummond agrees, supporting Glossip’s quest for a new trial. But the far-right Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ruled against him, and attempted to insulate its ruling from SCOTUS review by asserting that state law bars any further appeals. Now the Supreme Court must decide whether the lower court successfully thwarted federal reversal—and if not, whether Glossip deserves a new trial that complies with the Constitution.

Arguments were knotty, with a slim majority of justices potentially leaning in Glossip’s favor. They were dominated, though, by two justices on clear opposite sides of the case: Justice Clarence Thomas, a staunch supporter of speedy executions, and Sonia Sotomayor, a death penalty skeptic. Thomas went to bat for the prosecutors accused of misconduct, persistently defending their honor with deep empathy and concern for their reputations. Sotomayor, by contrast, emphasized strong evidence that these prosecutors willfully violated Glossip’s due process rights. The question now is whether either of them will win over Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, who hold the decisive votes. If both justices choose Sotomayor’s reality-based position over Thomas’ fantastical defense of the prosecutors, it will be an easy call.

One strange feature of Glossip is that everyone agrees Richard Glossip did not personally kill the victim, Barry Van Treese. It was, rather, Justin Sneed who killed Van Treese. Sneed then struck a deal with prosecutors to avoid a death sentence by testifying that Glossip ordered him to carry out the murder. Sneed’s testimony was central to the state’s case against Glossip, and prosecutors sought to prove he could be trusted. At one point, the lead prosecutor, Connie Smothermon, asked Sneed if he took medication; he told the jury he was once prescribed lithium for a “cold” but “never seen no psychiatrist or anything.”

Here’s the problem: Contemporaneous notes, uncovered years later, reflect prosecutors’ knowledge that Sneed was lying. These notes, taken by Smothermon, state that Sneed was “on lithium” and under the care of a “Dr. Trumpet.” The prison psychiatrist who treated Sneed was named “Dr. Trombka.” Glossip’s lawyers think Smothermon was referring to this doctor. They believe these notes show that Smothermon and her co-counsel, Gary Ackley, knew Dr. Trombka treated Sneed with lithium for a psychiatric disorder—but refused to share this information with Glossip.

These omissions are no small matter. The due process clause requires prosecutors to turn over potentially favorable evidence to the defense, and compels them to correct false testimony. Smothermon and Ackley did neither. If they had, Glossip’s attorneys might have undermined Sneed’s credibility by proving that he lied on the stand. They may have more persuasively painted him as the lone killer, too, since Trombka believed Sneed was capable of violent “manic episodes.” Because prosecutors chose to stay silent, Glossip’s attorneys could not make the strongest case for their client.

Yet during Wednesday’s arguments, Thomas sought to recast Smothermon and Ackley as innocent victims of a smear campaign. He immediately asked Seth Waxman, Glossip’s lawyer: “Did you at any point get a statement from either one of the prosecutors?” Waxman told him that he did, in fact, get a sworn statement from Ackley, and that Smothermon was interviewed by an independent counsel appointed by Drummond. So yes: Both prosecutors provided statements. Yet Thomas persisted as if they hadn’t. “It would seem that because not only their reputations are being impugned, but they are central to this case—it would seem that an interview of these two prosecutors would be central.” Waxman protested that, again, both prosecutors were given an opportunity to tell their side of the story. And again, Thomas refused to accept it: “They suggest,” the justice said, “that they were not sought out and given an opportunity to give detailed accounts of what those notes meant.”

In truth, Smothermon and Ackley have had ample opportunity to say their piece. Oklahoma Attorney General Drummond commissioned a thorough probe that included interviews with both prosecutors. Yet when Paul Clement—who represents Drummond—continued defending Glossip, Thomas made the same baseless accusation. “Shouldn’t these two prosecutors—it seems as though their reputations are being impugned,” Thomas told Clement, “and according to them, they did not receive an opportunity to explain in depth.” Clement responded that “that’s hard to square with the record here.” He pointed out that, on top of Drummond’s probe, the Oklahoma Legislature commissioned its own probe of the case, during which Smothermon and Ackley were interviewed.

Thomas then pivoted to minimizing the prosecutors’ misconduct, alternately dismissing the notes as inscrutable and crediting Smothermon’s “explanation” of their irrelevance. Clement explained that “the most plausible inference” is that the notes reveal unconstitutional concealment of evidence. Thomas pivoted back to his false claim that Glossip’s lawyers never spoke to the prosecutors, saying of Smothermon: “Her point is that you didn’t ask her, that you didn’t have an in-depth conversation with her about it. You’re drawing it from the note, which she thinks is inadequate information.”

This back-and-forth dragged on, with the justice refusing to accept reality. “Why wouldn’t they be interviewed?” he asked Clement again. “Why don’t we have materials from them other than in an amicus brief in this case?” Clement could only restate the fact: “Well, with respect, Justice Thomas,” he said, “you do have materials from them.” Thomas just wouldn’t hear it: “What are we to do with the point that they make that they were frozen out of the process?” he asked. An exasperated Clement only continued pointing the justice toward the prosecutors’ own statements.

And what did the prosecutors say to exonerate themselves? Smothermon has argued that Glossip’s defenders made an incorrect extrapolation. They say her note about “Dr. Trumpet” was a misspelling of Dr. Trombka, Sneed’s psychiatrist. Smothermon disagrees: She told an investigator, and later wrote in an email, that her note may refer to “Dr Trumpet the jazz musician.” She further suggested that she “was making a personal note or something else” about this mysterious trumpet player. She did not provide his true identity, only his alleged stage name. When the New York Times asked for further clarification, Smothermon responded that she does not “speak with members of the media” on principle.

Thomas ate up so much of argument time asking about the prosecutors that Sotomayor finally interjected. “I think, under the law, anything in the prosecutor’s possession, which includes prison records, the knowledge is imputed to the prosecutor, correct?” she asked. Clement agreed, adding that “there’s only one conclusion to be made here.” Sotomayor also asked if Clement knew “as a matter of fact” whether Smothermon was interviewed. He confirmed, for the dozenth time, that they were. “I’m having a hard time understanding what the current claim by both of them is: ‘We weren’t able to give our full story,’ ” Sotomayor continued. “It wasn’t as if they were boxed out?” Clement affirmed that they were not.

Why was Thomas fixated on this fantasy that the prosecutors were boxed out? It reads in part as misdirected empathy. In many death penalty case, Thomas expresses profound empathy for the victim and their family, then leverages this empathy to justify callous disregard for the defendant’s life. In Glossip, rather than pour his heart out for Van Treese, Thomas latched onto the prosecutors accused of violating due process. He bestowed upon Smothermon and Ackley a presumption of innocence that he so often denies to criminal defendants, including Glossip himself.

Neither Kavanaugh nor Barrett seemed persuaded by Thomas’ quest to rehabilitate the prosecutors. Kavanaugh appeared to grasp the injustice here; he mused that Sneed “lied on the stand,” creating “all sorts of avenues for questioning his credibility” that Glossip could not pursue, because prosecutors prevented his attorneys from seeing critical evidence. Barrett sounded stuck in the procedural morass created by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals in its bid to prevent SCOTUS from overruling it. Chief Justice John Roberts implied that any concealed evidence would be irrelevant to the jury anyway. With Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson lining up alongside Sotomayor, the case will likely come down to Kavanaugh and Barrett. (Justice Neil Gorsuch is recused due to participating in earlier proceedings on the lower court.)

Ultimately, Thomas’ questions on Wednesday functioned as smoke and mirrors, a feeble effort to absolve the alleged constitutional violation in this case by depicting prosecutors as victims of a witch hunt. The voluminous record in the case provides no support for this position. And when evidence suggests that prosecutors ran afoul of due process, they are not entitled to the benefit of the doubt. It should not be this difficult for five justices to see that Glossip got an unfair trial whose defects cannot be rationalized away today.

Arguments were knotty, with a slim majority of justices potentially leaning in Glossip’s favor. They were dominated, though, by two justices on clear opposite sides of the case: Justice Clarence Thomas, a staunch supporter of speedy executions, and Sonia Sotomayor, a death penalty skeptic. Thomas went to bat for the prosecutors accused of misconduct, persistently defending their honor with deep empathy and concern for their reputations. Sotomayor, by contrast, emphasized strong evidence that these prosecutors willfully violated Glossip’s due process rights. The question now is whether either of them will win over Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, who hold the decisive votes. If both justices choose Sotomayor’s reality-based position over Thomas’ fantastical defense of the prosecutors, it will be an easy call.

One strange feature of Glossip is that everyone agrees Richard Glossip did not personally kill the victim, Barry Van Treese. It was, rather, Justin Sneed who killed Van Treese. Sneed then struck a deal with prosecutors to avoid a death sentence by testifying that Glossip ordered him to carry out the murder. Sneed’s testimony was central to the state’s case against Glossip, and prosecutors sought to prove he could be trusted. At one point, the lead prosecutor, Connie Smothermon, asked Sneed if he took medication; he told the jury he was once prescribed lithium for a “cold” but “never seen no psychiatrist or anything.”

Here’s the problem: Contemporaneous notes, uncovered years later, reflect prosecutors’ knowledge that Sneed was lying. These notes, taken by Smothermon, state that Sneed was “on lithium” and under the care of a “Dr. Trumpet.” The prison psychiatrist who treated Sneed was named “Dr. Trombka.” Glossip’s lawyers think Smothermon was referring to this doctor. They believe these notes show that Smothermon and her co-counsel, Gary Ackley, knew Dr. Trombka treated Sneed with lithium for a psychiatric disorder—but refused to share this information with Glossip.

These omissions are no small matter. The due process clause requires prosecutors to turn over potentially favorable evidence to the defense, and compels them to correct false testimony. Smothermon and Ackley did neither. If they had, Glossip’s attorneys might have undermined Sneed’s credibility by proving that he lied on the stand. They may have more persuasively painted him as the lone killer, too, since Trombka believed Sneed was capable of violent “manic episodes.” Because prosecutors chose to stay silent, Glossip’s attorneys could not make the strongest case for their client.

Yet during Wednesday’s arguments, Thomas sought to recast Smothermon and Ackley as innocent victims of a smear campaign. He immediately asked Seth Waxman, Glossip’s lawyer: “Did you at any point get a statement from either one of the prosecutors?” Waxman told him that he did, in fact, get a sworn statement from Ackley, and that Smothermon was interviewed by an independent counsel appointed by Drummond. So yes: Both prosecutors provided statements. Yet Thomas persisted as if they hadn’t. “It would seem that because not only their reputations are being impugned, but they are central to this case—it would seem that an interview of these two prosecutors would be central.” Waxman protested that, again, both prosecutors were given an opportunity to tell their side of the story. And again, Thomas refused to accept it: “They suggest,” the justice said, “that they were not sought out and given an opportunity to give detailed accounts of what those notes meant.”

In truth, Smothermon and Ackley have had ample opportunity to say their piece. Oklahoma Attorney General Drummond commissioned a thorough probe that included interviews with both prosecutors. Yet when Paul Clement—who represents Drummond—continued defending Glossip, Thomas made the same baseless accusation. “Shouldn’t these two prosecutors—it seems as though their reputations are being impugned,” Thomas told Clement, “and according to them, they did not receive an opportunity to explain in depth.” Clement responded that “that’s hard to square with the record here.” He pointed out that, on top of Drummond’s probe, the Oklahoma Legislature commissioned its own probe of the case, during which Smothermon and Ackley were interviewed.

Thomas then pivoted to minimizing the prosecutors’ misconduct, alternately dismissing the notes as inscrutable and crediting Smothermon’s “explanation” of their irrelevance. Clement explained that “the most plausible inference” is that the notes reveal unconstitutional concealment of evidence. Thomas pivoted back to his false claim that Glossip’s lawyers never spoke to the prosecutors, saying of Smothermon: “Her point is that you didn’t ask her, that you didn’t have an in-depth conversation with her about it. You’re drawing it from the note, which she thinks is inadequate information.”

This back-and-forth dragged on, with the justice refusing to accept reality. “Why wouldn’t they be interviewed?” he asked Clement again. “Why don’t we have materials from them other than in an amicus brief in this case?” Clement could only restate the fact: “Well, with respect, Justice Thomas,” he said, “you do have materials from them.” Thomas just wouldn’t hear it: “What are we to do with the point that they make that they were frozen out of the process?” he asked. An exasperated Clement only continued pointing the justice toward the prosecutors’ own statements.

And what did the prosecutors say to exonerate themselves? Smothermon has argued that Glossip’s defenders made an incorrect extrapolation. They say her note about “Dr. Trumpet” was a misspelling of Dr. Trombka, Sneed’s psychiatrist. Smothermon disagrees: She told an investigator, and later wrote in an email, that her note may refer to “Dr Trumpet the jazz musician.” She further suggested that she “was making a personal note or something else” about this mysterious trumpet player. She did not provide his true identity, only his alleged stage name. When the New York Times asked for further clarification, Smothermon responded that she does not “speak with members of the media” on principle.

Thomas ate up so much of argument time asking about the prosecutors that Sotomayor finally interjected. “I think, under the law, anything in the prosecutor’s possession, which includes prison records, the knowledge is imputed to the prosecutor, correct?” she asked. Clement agreed, adding that “there’s only one conclusion to be made here.” Sotomayor also asked if Clement knew “as a matter of fact” whether Smothermon was interviewed. He confirmed, for the dozenth time, that they were. “I’m having a hard time understanding what the current claim by both of them is: ‘We weren’t able to give our full story,’ ” Sotomayor continued. “It wasn’t as if they were boxed out?” Clement affirmed that they were not.

Why was Thomas fixated on this fantasy that the prosecutors were boxed out? It reads in part as misdirected empathy. In many death penalty case, Thomas expresses profound empathy for the victim and their family, then leverages this empathy to justify callous disregard for the defendant’s life. In Glossip, rather than pour his heart out for Van Treese, Thomas latched onto the prosecutors accused of violating due process. He bestowed upon Smothermon and Ackley a presumption of innocence that he so often denies to criminal defendants, including Glossip himself.

Neither Kavanaugh nor Barrett seemed persuaded by Thomas’ quest to rehabilitate the prosecutors. Kavanaugh appeared to grasp the injustice here; he mused that Sneed “lied on the stand,” creating “all sorts of avenues for questioning his credibility” that Glossip could not pursue, because prosecutors prevented his attorneys from seeing critical evidence. Barrett sounded stuck in the procedural morass created by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals in its bid to prevent SCOTUS from overruling it. Chief Justice John Roberts implied that any concealed evidence would be irrelevant to the jury anyway. With Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson lining up alongside Sotomayor, the case will likely come down to Kavanaugh and Barrett. (Justice Neil Gorsuch is recused due to participating in earlier proceedings on the lower court.)

Ultimately, Thomas’ questions on Wednesday functioned as smoke and mirrors, a feeble effort to absolve the alleged constitutional violation in this case by depicting prosecutors as victims of a witch hunt. The voluminous record in the case provides no support for this position. And when evidence suggests that prosecutors ran afoul of due process, they are not entitled to the benefit of the doubt. It should not be this difficult for five justices to see that Glossip got an unfair trial whose defects cannot be rationalized away today.

Comments( 0 )

0 0 0

0 0 2