Finally, the Bad Guys Had a Bad Day at the Supreme Court

Posted on 10/09/2024

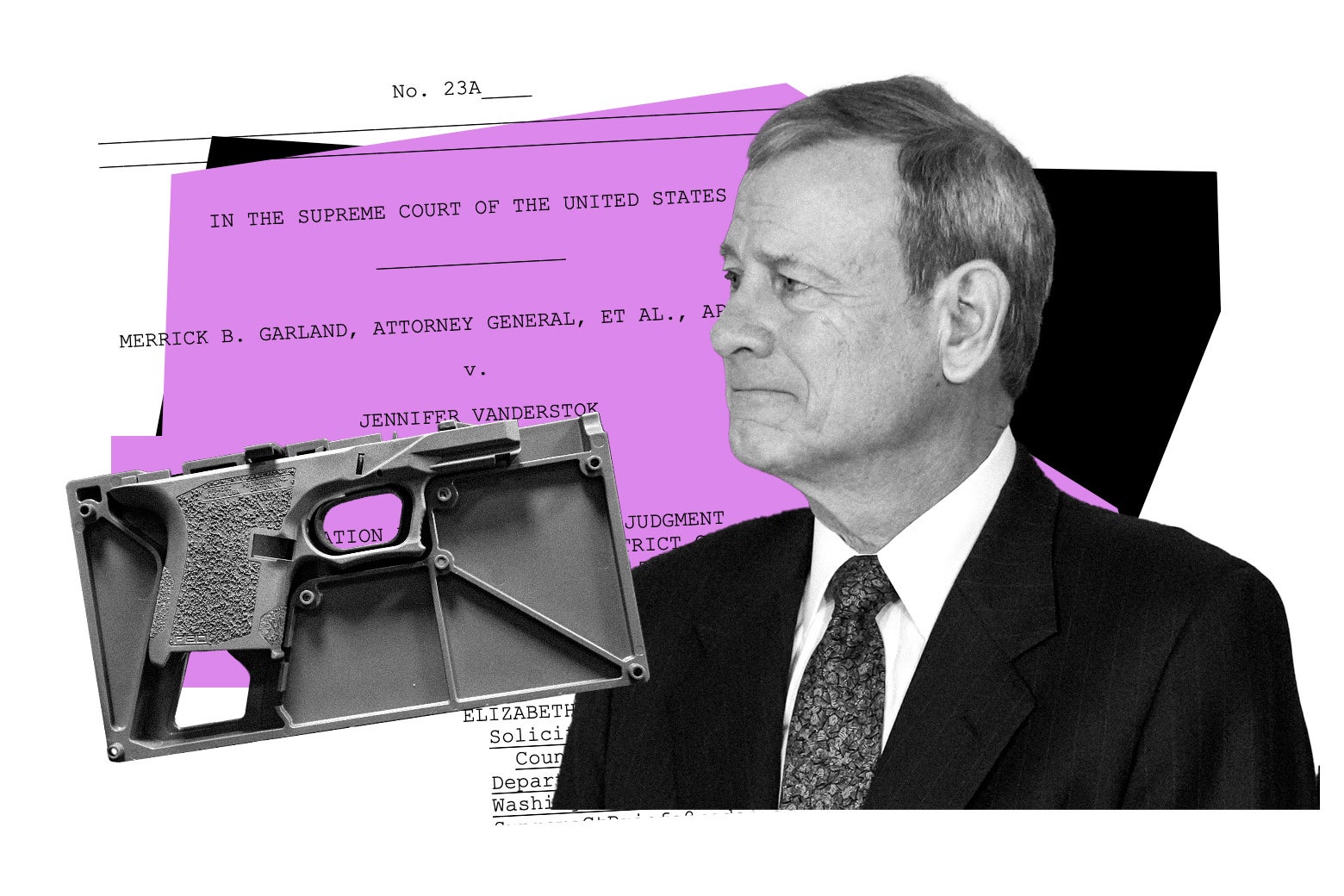

Lawyers with bad arguments in defense of terrible causes are on a winning streak at this Supreme Court. The conservative supermajority often seems committed to laundering feeble and nutty arguments into plausible-sounding law on behalf of right-wing litigants. It was therefore more gratifying than it should have been on Tuesday to hear the court regain its sanity, if only temporarily, to smack down the ghost gun industry’s bid for resurrection. A clear majority of the justices appears poised to uphold a Biden administration rule that has effectively put this industry—which sells untraceable guns that are disproportionately used in crimes—out of business. These justices did not mask their irritation with the lower court judges who tried to save the ghost gun companies, along with their criminal clientele, by warping the law beyond all recognition. Nor did the justices conceal their distaste, verging on mocking contempt, for the lawyer whom these merchants of death handpicked to make their case to SCOTUS. Real law is back at the Supreme Court, and even if it’s for one case only, the development remains worthy of celebration.

That case, Garland v. VanDerStok, is partly a cautionary tale about pride before the fall. Starting around 2017, online gun companies scaled up a new business model: selling kits directly to consumers with all the parts needed to assemble a functioning firearm. Customers could purchase the gun without a background check and put it together in as little as 20 minutes with the help of a YouTube video; the resulting firearm would have no serial number, rendering it untraceable by law enforcement. These businesses boasted about circumventing federal law, assuring buyers that they did not “have to worry” about a background check and could use their “unmarked and unserialized” weapon without any “documentation” that would trace it to them. One company printed an image of a raised middle finger on a product with the text: “Here’s your serial number.” This model operated as an assault weapon.

The number of ghost guns used in violent crimes promptly skyrocketed in cities across the country, with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives reporting a 1,000 percent increase between 2017 and 2021. So, in 2022, Biden’s ATF proposed a new rule that would finally limit the sale of these weapons nationwide. The agency announced that gun kit sellers had to comply with the requirements that apply to other gun dealers—including serialization and a background check. For support, it cited the Gun Control Act of 1968, which applies to any combination of parts that “may readily be converted” into a firing weapon.

ATF’s rule devastated the ghost gun industry, which catered to customers with criminal records who would flunk a background check. After it took effect in 2023, the industry largely collapsed, and the number of ghost guns collected at crime scenes plummeted. Now the companies are begging SCOTUS to strike down the rule and allow them to continue flooding the streets with untraceable firearms.

The Supreme Court has actually dealt with VanDerStok before. When ATF tried to implement the ghost guns rule, the far-right U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor issued a sweeping injunction blocking it nationwide. The equally fringe-right U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit declined to halt his decision blocking the new regulation. The Supreme Court then stepped in, freezing O’Connor’s decision and letting the rule go into effect. It was a 5–4 vote, with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett joining the three liberals. O’Connor then defied SCOTUS, issuing yet another injunction protecting two major sellers—which the 5th Circuit again declined to halt; this time, the Supreme Court froze O’Connor’s decision with no noted dissents. Remarkably, the 5th Circuit failed to take the hint, and purported to strike down the rule nationwide. That’s why Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar was back at SCOTUS on Tuesday seeking an end to the merry-go-round of lower court lawlessness.

Tuesday’s arguments revealed two things: Roberts and Barrett have zero sympathy for the ghost gun industry, and they are unmistakably sick of this never-ending case. Again, the legal question is not difficult: Under federal law, parts that “may readily be converted” to fire a bullet are a firearm, so their sale must comply with the usual regulations, including needing a serial number and background check. Justice Samuel Alito predictably tried to muddle this legal clarity, asking Prelogar: “If I put out on a counter some eggs, some chopped-up ham, some chopped-up pepper, and onions, is that a western omelet?” Prelogar said no, because unlike the parts in a ghost gun kit, “those items have well-known other uses to become something other than an omelet.” Barrett then chimed in: “Would your answer change if you ordered it from HelloFresh and you got a kit, and it was like, turkey chili, but all of the ingredients are in the kit?” Prelogar agreed that this was “the more apt analogy here.”

As this exchange illustrates, Barrett seemed eager to knock down bad arguments all morning. At one point, she cited a risible claim made by Judge Andrew Oldham, a Trump appointee on the 5th Circuit. “So Judge Oldham expressed concern that because AR-15 receivers can be readily converted into machine gun receivers, that this regulation on its face turns everyone who lawfully owns an AR-15 into a criminal,” Barrett told Prelogar.

“That is wrong,” Prelogar responded. “We are not suggesting that a statutory reference to one thing includes all other separate and distinct things that might be readily converted into the thing that’s listed in the statute itself.” Because, well, of course the solicitor general is not making such an asinine argument. It’s just a straw man that Oldham dreamed up to defend ghost gun buyers—whom he depicted, with a straight face, as noble, “law-abiding” gunsmiths partaking in a grand American “tradition of self-made arms.”

When Peter A. Patterson approached the lectern to defend the ghost gun industry, he faced almost withering skepticism from Barrett and Roberts. Patterson argued that the court should allow ATF to regulate only firearms that have been completed with “critical machining operations.” But, Barrett pointed out, that language “doesn’t appear in the statute,” adding sharply: “It seems a little made-up.” Patterson also tried to promote the idea that ghost gun companies weren’t intentionally skirting the law by selling “frames or receivers,” the core component of a firearm, that could be transformed into a functioning weapon by drilling a few holes. Roberts was not buying it.

“Just what is the purpose of selling a receiver without the holes drilled in it?” the chief justice asked.

“Well, just like some individuals enjoy, like, working on their car every weekend, some individuals want to construct their own firearm,” Patterson responded.

“Well, I mean, drilling a hole or two, I would think, doesn’t give the same sort of reward that you get from working on your car on the weekends,” the chief retorted. Patterson did not seem to realize that Roberts was making fun of him; he asserted that it’s actually very difficult to put together a ghost gun, citing an article by a journalist who struggled to assemble one himself. “I don’t know the skills of the particular reporter,” Roberts said, “but my understanding is that it’s not terribly difficult for someone to do this.” He pointed out that some ghost guns are assembled by removing plastic pieces. “Is that part of the gunsmithing?” he added dryly.

Patterson insisted that making minor modifications to a mostly assembled gun qualifies as gunsmithing. Roberts was not convinced, asking: “I’m suggesting that if someone who goes through the process of drilling the one or two holes and taking the plastic out, he really wouldn’t think that he has built that gun, would he?” Patterson told the chief: “I don’t know what that person would think, but I think he would.” It did not sound like a winning argument.

The low point for Patterson arrived when Roberts asked his colleagues if they had any final questions. Usually, justices use this opportunity to slip in a last objection or concern. This time, they were silent. Nobody wanted to hear another word from the ghost gun guy.

In fairness, Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch peppered Patterson with favorable softballs, some of which the attorney bafflingly whiffed. (At one point, Thomas was nearly pleading with Patterson to give the answer he wanted to hear.) Alito will likely side with him as well. But even Kavanaugh—who voted to preserve the lower courts’ nationwide block on ATF’s rule last year—has seemingly come around to Prelogar’s side. “Your statutory interpretation has force,” Kavanaugh told the solicitor general, then suggested that he previously voted against the rule because it might ensnare innocent people. He solicited “assurances” from Prelogar that the government would not prosecute a seller “who is truly not aware that they are violating the law,” which she provided. Meanwhile, Kavanaugh didn’t bother to ask Patterson a single question. By the end of arguments, you could practically hear the 6–3 majority clicking into place.

A victory for ATF in VanDerStok will be a triumph for sane judging and commonsense gun safety laws; it will also literally save countless people’s lives. But there’s a dark cloud overhead: If Trump wins in November, he will direct ATF to rescind the rule, since it was his administration that allowed ghost gun sellers to flourish in the first place. Put bluntly, VanDerStok only matters if Trump loses. Perhaps the takeaway from Tuesday, then, is that wins at the Supreme Court, however gratifying, are still not enough. Anyone who would rather not risk being shot by a ghost gun needs to vote like their life depends on it.

That case, Garland v. VanDerStok, is partly a cautionary tale about pride before the fall. Starting around 2017, online gun companies scaled up a new business model: selling kits directly to consumers with all the parts needed to assemble a functioning firearm. Customers could purchase the gun without a background check and put it together in as little as 20 minutes with the help of a YouTube video; the resulting firearm would have no serial number, rendering it untraceable by law enforcement. These businesses boasted about circumventing federal law, assuring buyers that they did not “have to worry” about a background check and could use their “unmarked and unserialized” weapon without any “documentation” that would trace it to them. One company printed an image of a raised middle finger on a product with the text: “Here’s your serial number.” This model operated as an assault weapon.

The number of ghost guns used in violent crimes promptly skyrocketed in cities across the country, with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives reporting a 1,000 percent increase between 2017 and 2021. So, in 2022, Biden’s ATF proposed a new rule that would finally limit the sale of these weapons nationwide. The agency announced that gun kit sellers had to comply with the requirements that apply to other gun dealers—including serialization and a background check. For support, it cited the Gun Control Act of 1968, which applies to any combination of parts that “may readily be converted” into a firing weapon.

ATF’s rule devastated the ghost gun industry, which catered to customers with criminal records who would flunk a background check. After it took effect in 2023, the industry largely collapsed, and the number of ghost guns collected at crime scenes plummeted. Now the companies are begging SCOTUS to strike down the rule and allow them to continue flooding the streets with untraceable firearms.

The Supreme Court has actually dealt with VanDerStok before. When ATF tried to implement the ghost guns rule, the far-right U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor issued a sweeping injunction blocking it nationwide. The equally fringe-right U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit declined to halt his decision blocking the new regulation. The Supreme Court then stepped in, freezing O’Connor’s decision and letting the rule go into effect. It was a 5–4 vote, with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett joining the three liberals. O’Connor then defied SCOTUS, issuing yet another injunction protecting two major sellers—which the 5th Circuit again declined to halt; this time, the Supreme Court froze O’Connor’s decision with no noted dissents. Remarkably, the 5th Circuit failed to take the hint, and purported to strike down the rule nationwide. That’s why Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar was back at SCOTUS on Tuesday seeking an end to the merry-go-round of lower court lawlessness.

Tuesday’s arguments revealed two things: Roberts and Barrett have zero sympathy for the ghost gun industry, and they are unmistakably sick of this never-ending case. Again, the legal question is not difficult: Under federal law, parts that “may readily be converted” to fire a bullet are a firearm, so their sale must comply with the usual regulations, including needing a serial number and background check. Justice Samuel Alito predictably tried to muddle this legal clarity, asking Prelogar: “If I put out on a counter some eggs, some chopped-up ham, some chopped-up pepper, and onions, is that a western omelet?” Prelogar said no, because unlike the parts in a ghost gun kit, “those items have well-known other uses to become something other than an omelet.” Barrett then chimed in: “Would your answer change if you ordered it from HelloFresh and you got a kit, and it was like, turkey chili, but all of the ingredients are in the kit?” Prelogar agreed that this was “the more apt analogy here.”

As this exchange illustrates, Barrett seemed eager to knock down bad arguments all morning. At one point, she cited a risible claim made by Judge Andrew Oldham, a Trump appointee on the 5th Circuit. “So Judge Oldham expressed concern that because AR-15 receivers can be readily converted into machine gun receivers, that this regulation on its face turns everyone who lawfully owns an AR-15 into a criminal,” Barrett told Prelogar.

“That is wrong,” Prelogar responded. “We are not suggesting that a statutory reference to one thing includes all other separate and distinct things that might be readily converted into the thing that’s listed in the statute itself.” Because, well, of course the solicitor general is not making such an asinine argument. It’s just a straw man that Oldham dreamed up to defend ghost gun buyers—whom he depicted, with a straight face, as noble, “law-abiding” gunsmiths partaking in a grand American “tradition of self-made arms.”

When Peter A. Patterson approached the lectern to defend the ghost gun industry, he faced almost withering skepticism from Barrett and Roberts. Patterson argued that the court should allow ATF to regulate only firearms that have been completed with “critical machining operations.” But, Barrett pointed out, that language “doesn’t appear in the statute,” adding sharply: “It seems a little made-up.” Patterson also tried to promote the idea that ghost gun companies weren’t intentionally skirting the law by selling “frames or receivers,” the core component of a firearm, that could be transformed into a functioning weapon by drilling a few holes. Roberts was not buying it.

“Just what is the purpose of selling a receiver without the holes drilled in it?” the chief justice asked.

“Well, just like some individuals enjoy, like, working on their car every weekend, some individuals want to construct their own firearm,” Patterson responded.

“Well, I mean, drilling a hole or two, I would think, doesn’t give the same sort of reward that you get from working on your car on the weekends,” the chief retorted. Patterson did not seem to realize that Roberts was making fun of him; he asserted that it’s actually very difficult to put together a ghost gun, citing an article by a journalist who struggled to assemble one himself. “I don’t know the skills of the particular reporter,” Roberts said, “but my understanding is that it’s not terribly difficult for someone to do this.” He pointed out that some ghost guns are assembled by removing plastic pieces. “Is that part of the gunsmithing?” he added dryly.

Patterson insisted that making minor modifications to a mostly assembled gun qualifies as gunsmithing. Roberts was not convinced, asking: “I’m suggesting that if someone who goes through the process of drilling the one or two holes and taking the plastic out, he really wouldn’t think that he has built that gun, would he?” Patterson told the chief: “I don’t know what that person would think, but I think he would.” It did not sound like a winning argument.

The low point for Patterson arrived when Roberts asked his colleagues if they had any final questions. Usually, justices use this opportunity to slip in a last objection or concern. This time, they were silent. Nobody wanted to hear another word from the ghost gun guy.

In fairness, Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch peppered Patterson with favorable softballs, some of which the attorney bafflingly whiffed. (At one point, Thomas was nearly pleading with Patterson to give the answer he wanted to hear.) Alito will likely side with him as well. But even Kavanaugh—who voted to preserve the lower courts’ nationwide block on ATF’s rule last year—has seemingly come around to Prelogar’s side. “Your statutory interpretation has force,” Kavanaugh told the solicitor general, then suggested that he previously voted against the rule because it might ensnare innocent people. He solicited “assurances” from Prelogar that the government would not prosecute a seller “who is truly not aware that they are violating the law,” which she provided. Meanwhile, Kavanaugh didn’t bother to ask Patterson a single question. By the end of arguments, you could practically hear the 6–3 majority clicking into place.

A victory for ATF in VanDerStok will be a triumph for sane judging and commonsense gun safety laws; it will also literally save countless people’s lives. But there’s a dark cloud overhead: If Trump wins in November, he will direct ATF to rescind the rule, since it was his administration that allowed ghost gun sellers to flourish in the first place. Put bluntly, VanDerStok only matters if Trump loses. Perhaps the takeaway from Tuesday, then, is that wins at the Supreme Court, however gratifying, are still not enough. Anyone who would rather not risk being shot by a ghost gun needs to vote like their life depends on it.

Comments( 0 )

0 0 0

0 0 2

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/adn/JF6FH7DLYVBLZMKLMUUM52A2CI.JPG)