Oklahoma man says he didn't commit the crime he's set to die for. Will the governor spare him?

Posted on 09/25/2024

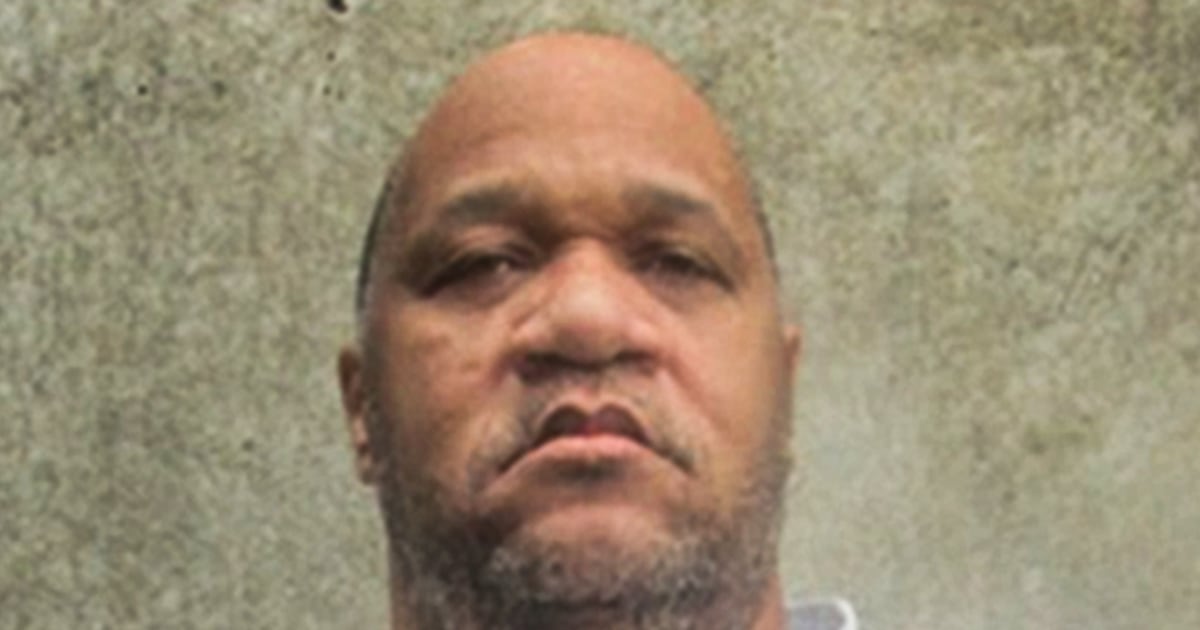

Emmanuel Littlejohn, 52, is set to be executed in Oklahoma on Thursday — but nobody knows whether he’s truly guilty of the crime for which he was condemned.

Littlejohn was convicted of murdering Kenneth Meers, 31, during a robbery at the Root-N-Scoot convenience store Meers owned in Oklahoma City in 1992. Meers was shot and killed by a single bullet, but both men who took part in the robbery — Littlejohn, then 20 years old, and Glenn Bethany, then 26 — were charged and convicted in his murder.

Littlejohn and his legal team have argued that his accomplice was the sole shooter and that he should not be executed because his case involves “inconsistent prosecutions.” Multiple jurors submitted sworn affidavits in support of Littlejohn’s clemency, claiming they mistakenly voted for the death penalty because they misunderstood how a sentence of life without parole works.

“I would have been OK with a life sentence,” Littlejohn said in an interview last month. “But a death sentence for robbery? I’m not cool with that.”

While Littlejohn has exhausted his appeals, he awaits a clemency decision from Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, after the state parole board voted 3-2 to recommend commuting his sentence to life without parole.

Both Bethany and Littlejohn could be charged with the crime because of a statute called felony murder, which allows anyone who is charged with a violent felony to also be charged with murder if the crime results in a death.

But Littlejohn’s lawyers have argued for decades that he should not be executed because prosecutors offered contradictory accounts of Meers’ murder — arguing first in Bethany’s trial that Bethany was the shooter and then arguing that Littlejohn was the shooter in his own trial after Bethany had already been convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole.

“You must carefully scrutinize the testimony of everyone, which includes the testimony of the people across the street, who are certain that it was the taller of the two individuals who stood at the door and fired a shot back inside,” the prosecution told the jury during Bethany’s trial. (Bethany is the taller of the two men.)

“They murdered Kenneth Meers,” the prosecution said. “The question is whether you believe he is the shooter or the other man who was inside the store that day. Either way, he’s guilty of murder.”

When Littlejohn went to trial the next year, the prosecution argued that he was the one who fired the shot that killed Meers, saying he was the only one who had a gun during the robbery.

In an interview, Littlejohn acknowledged his part in the robbery, which he described as a drug deal gone wrong.

“Me and Glenn Bethany was selling dope,” he said. “We had got this dope from one drug dealer. When it came time to pay, Glenn didn’t have all his money.

“We owed him $1,500. Glenn smoked all the dope. He said, ‘Give me my money, or I’m gonna kill you.’ That’s when we started looking at stores to rob,” Littlejohn said.

But he maintained he did not fire the fatal shot.

“All I know is when I left the store, Mr. Meers was still alive,” he said. “I didn’t kill Mr. Meers.”

Bethany did not respond to a request for an interview.

It is not the first time Littlejohn has faced an opportunity to overturn his death sentence. In 1998, the Oklahoma Criminal Court of Appeals vacated the death sentence and ordered a resentencing.

“The evidence was less than conclusive as to the identity of the shooter,” the court wrote at the time while maintaining that prosecutors did not act inappropriately in presenting both Littlejohn and Bethany as the shooter.

In 2000, a second jury sentenced Littlejohn to death.

But according to Littlejohn’s clemency petition, jurors involved in his sentences were confused about the meaning of “life without the possibility of parole.” Such a sentence was relatively new at the time in Oklahoma, the petition said, so jurors were confused about whether it meant Littlejohn could somehow be released one day — even though life without parole sentences do not allow for such outcomes.

Two jurors from Littlejohn’s 1994 and 2000 sentencings provided sworn affidavits in the clemency petition saying that they did not think death is an appropriate sentence but that they chose it out of concern he might one day walk free.

One juror said she “changed her vote to death because she ‘felt the alternative was that he would get loose’ and that a ‘life sentence even without parole could be changed and he might have a chance to get out of prison.’” Another said that, in hindsight, she “‘would not vote for death’ but instead ‘for life without the possibility of parole and stick with it.’”

The Pardon and Parole Board voted 3-2 to recommend clemency for Littlejohn last month.

In a statement, state Attorney General Gentner Drummond came out against the decision, saying, “My office intends to make our case to the governor why there should not be clemency granted to this violent and manipulative killer.”

Now the decision of whether to spare Littlejohn rests with Stitt, the governor, who has granted clemency only once, while the board has recommended clemency for death row inmates five times.

“Governor Stitt has met with those involved in the case, including family members, prosecutors, victims, and the defense. The Governor has not reached a decision in this case yet, and he continues to prayerfully and carefully considers the facts, evidence, and recommendations from the Pardon and Parole Board,” a spokesperson for Stitt’s office said in a statement.

Littlejohn hopes Stitt will grant him clemency so he can spend more time with his daughter and his new grandchild.

“I know it’s hard for him to do, but I have faith in him that he can do it,” Littlejohn says. “I just want him to spare my life, let me live a life.”

Littlejohn was convicted of murdering Kenneth Meers, 31, during a robbery at the Root-N-Scoot convenience store Meers owned in Oklahoma City in 1992. Meers was shot and killed by a single bullet, but both men who took part in the robbery — Littlejohn, then 20 years old, and Glenn Bethany, then 26 — were charged and convicted in his murder.

Littlejohn and his legal team have argued that his accomplice was the sole shooter and that he should not be executed because his case involves “inconsistent prosecutions.” Multiple jurors submitted sworn affidavits in support of Littlejohn’s clemency, claiming they mistakenly voted for the death penalty because they misunderstood how a sentence of life without parole works.

“I would have been OK with a life sentence,” Littlejohn said in an interview last month. “But a death sentence for robbery? I’m not cool with that.”

While Littlejohn has exhausted his appeals, he awaits a clemency decision from Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, after the state parole board voted 3-2 to recommend commuting his sentence to life without parole.

Both Bethany and Littlejohn could be charged with the crime because of a statute called felony murder, which allows anyone who is charged with a violent felony to also be charged with murder if the crime results in a death.

But Littlejohn’s lawyers have argued for decades that he should not be executed because prosecutors offered contradictory accounts of Meers’ murder — arguing first in Bethany’s trial that Bethany was the shooter and then arguing that Littlejohn was the shooter in his own trial after Bethany had already been convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole.

“You must carefully scrutinize the testimony of everyone, which includes the testimony of the people across the street, who are certain that it was the taller of the two individuals who stood at the door and fired a shot back inside,” the prosecution told the jury during Bethany’s trial. (Bethany is the taller of the two men.)

“They murdered Kenneth Meers,” the prosecution said. “The question is whether you believe he is the shooter or the other man who was inside the store that day. Either way, he’s guilty of murder.”

When Littlejohn went to trial the next year, the prosecution argued that he was the one who fired the shot that killed Meers, saying he was the only one who had a gun during the robbery.

In an interview, Littlejohn acknowledged his part in the robbery, which he described as a drug deal gone wrong.

“Me and Glenn Bethany was selling dope,” he said. “We had got this dope from one drug dealer. When it came time to pay, Glenn didn’t have all his money.

“We owed him $1,500. Glenn smoked all the dope. He said, ‘Give me my money, or I’m gonna kill you.’ That’s when we started looking at stores to rob,” Littlejohn said.

But he maintained he did not fire the fatal shot.

“All I know is when I left the store, Mr. Meers was still alive,” he said. “I didn’t kill Mr. Meers.”

Bethany did not respond to a request for an interview.

It is not the first time Littlejohn has faced an opportunity to overturn his death sentence. In 1998, the Oklahoma Criminal Court of Appeals vacated the death sentence and ordered a resentencing.

“The evidence was less than conclusive as to the identity of the shooter,” the court wrote at the time while maintaining that prosecutors did not act inappropriately in presenting both Littlejohn and Bethany as the shooter.

In 2000, a second jury sentenced Littlejohn to death.

But according to Littlejohn’s clemency petition, jurors involved in his sentences were confused about the meaning of “life without the possibility of parole.” Such a sentence was relatively new at the time in Oklahoma, the petition said, so jurors were confused about whether it meant Littlejohn could somehow be released one day — even though life without parole sentences do not allow for such outcomes.

Two jurors from Littlejohn’s 1994 and 2000 sentencings provided sworn affidavits in the clemency petition saying that they did not think death is an appropriate sentence but that they chose it out of concern he might one day walk free.

One juror said she “changed her vote to death because she ‘felt the alternative was that he would get loose’ and that a ‘life sentence even without parole could be changed and he might have a chance to get out of prison.’” Another said that, in hindsight, she “‘would not vote for death’ but instead ‘for life without the possibility of parole and stick with it.’”

The Pardon and Parole Board voted 3-2 to recommend clemency for Littlejohn last month.

In a statement, state Attorney General Gentner Drummond came out against the decision, saying, “My office intends to make our case to the governor why there should not be clemency granted to this violent and manipulative killer.”

Now the decision of whether to spare Littlejohn rests with Stitt, the governor, who has granted clemency only once, while the board has recommended clemency for death row inmates five times.

“Governor Stitt has met with those involved in the case, including family members, prosecutors, victims, and the defense. The Governor has not reached a decision in this case yet, and he continues to prayerfully and carefully considers the facts, evidence, and recommendations from the Pardon and Parole Board,” a spokesperson for Stitt’s office said in a statement.

Littlejohn hopes Stitt will grant him clemency so he can spend more time with his daughter and his new grandchild.

“I know it’s hard for him to do, but I have faith in him that he can do it,” Littlejohn says. “I just want him to spare my life, let me live a life.”

Comments( 0 )

0 0 0

0 0 2

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/adn/JF6FH7DLYVBLZMKLMUUM52A2CI.JPG)